The Night-War

Towns and countryside in darkness, repairing bombers for another night raid over Germany, many shot down, others crash-land in sudden explosions of fire, a night-war with no end in sight, young men far from home, and a fragment...

To live in Yorkshire in the 1940s was extraordinary - dangerous, exciting, unpredictable - like nothing before or since in this country, with thousands of young men, many foreigners, busy about the business of living and dying in the Night-War. I was shocked to discover the scale and ferocity of what went on, at home as well as over enemy territory...

Chapter 1

Bomber Boys

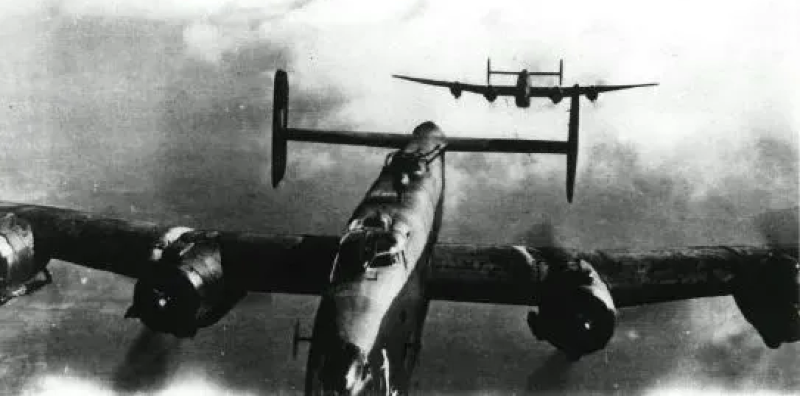

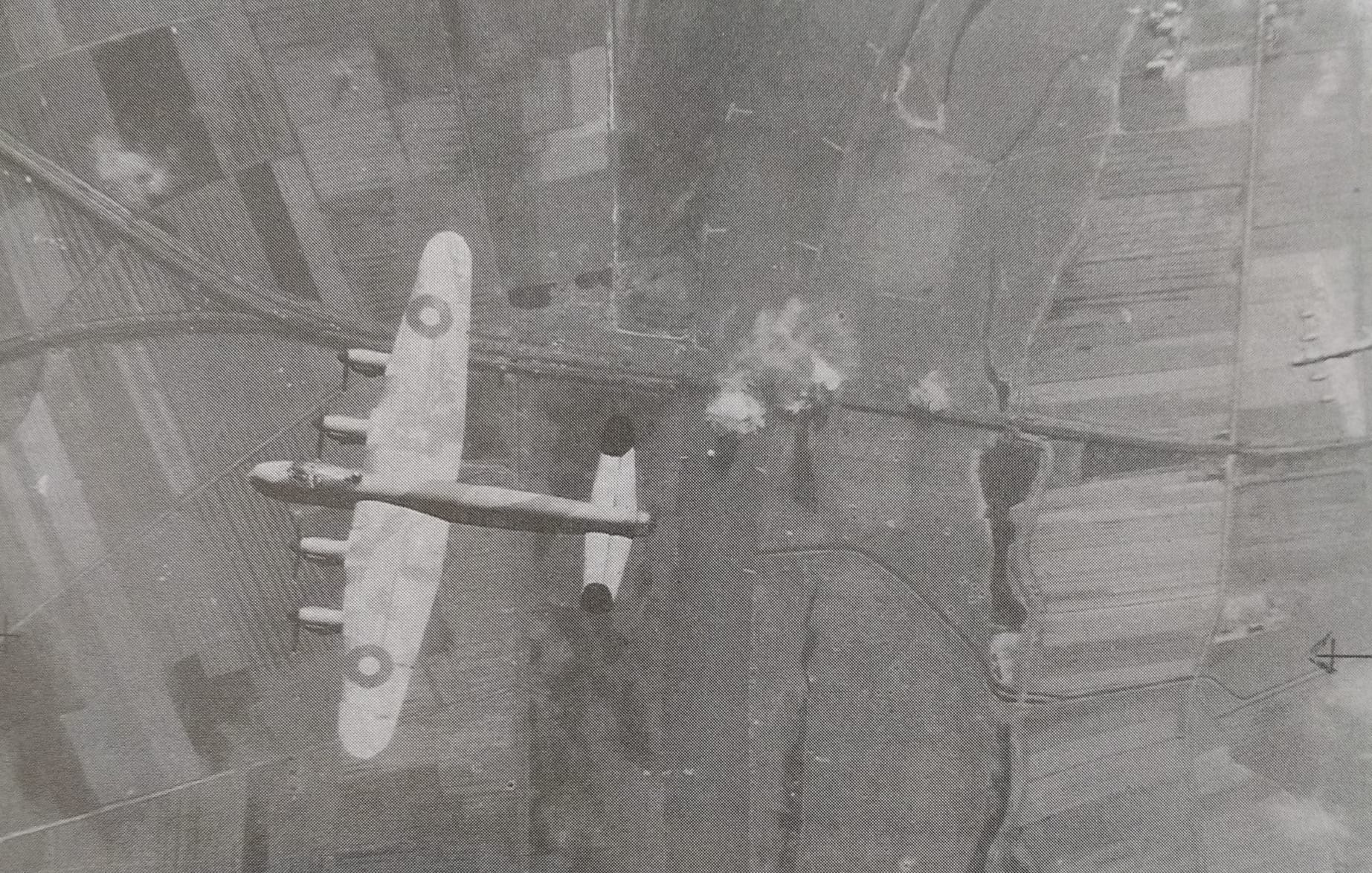

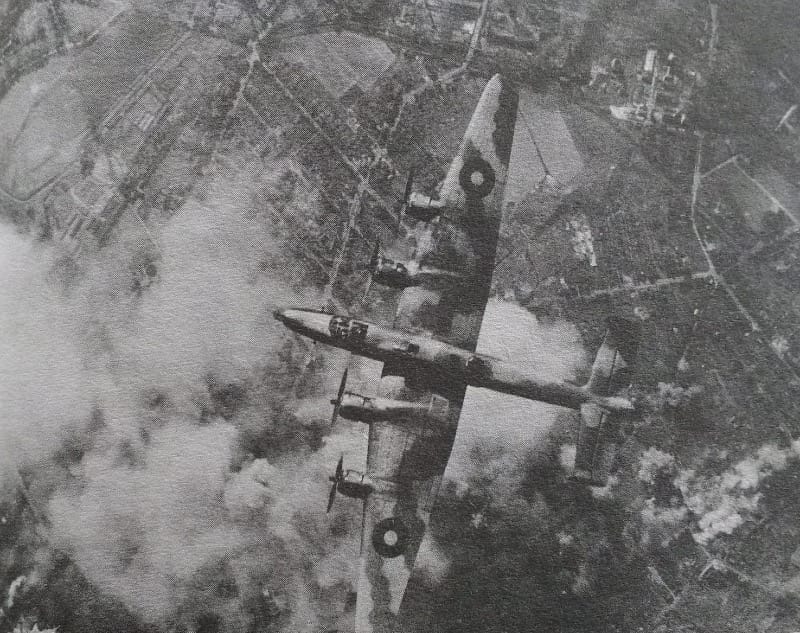

And boys they were, boys and young men, in their thousands, with barely a few hours of training doing something never done before - taking huge new aircraft loaded with explosives into the night skies to find their way across sea and land to Germany, and then find their way back in the darkness - hopefully. Night after night, across blacked-out countryside to enemy territory, barely any navigational aids initially, through rain, wind and sub-zero temperatures, to be met by searchlights, flak and enemy fighters. The casualty rate of aircrew and aircraft was appalling, not just once, but for years. As a final horror, the lucky survivors might crash-land their damaged planes on the return.

The aircraft were new, of a complexity and size never used before, flying them such distances and at night had never been done before, the tactics and the sheer number of planes flying through the darkness together - often over a thousand - had never been done before. This went on year after year. On every night's operation each man knew that even if he survived some of his friends would surely be killed. From teenage aircrew to ground commanders some not much older, they conducted the night bombing campaign of the Second World War, which was one hell of a 'first'.

And for many, just hell. It was only young men who could have endured such experiences night after night for five years. With blind courage, and surely with a fatalism as so much that decided if they lived or died was beyond their control. Some survived.

There was no institutional knowledge backing up what these young men were expected to do; some older senior officers may have had flying experience over 20 years earlier in the First World War, but that was very different - biplanes with one or two-man crews, flying short distances at low altitudes, mostly reconaissance missions. Thorough training can give confidence in performing a new task, but aircrew had little training, the roles of navigator, radio operator and bomb aimer had not been properly established. Nothing about their 'working environment' gave strength and confidence to aircrew: temperatures were many degrees subzero, despite bulky clothing which hampered movement in the cramped fuselages (unpressurised so oxygen masks had to be worn; all the bombers were drafty, without effective heating. The early, two-engined bombers were limited in speed and height; newer four-engined bombers flew higher, faster and further but were less manoeuvrable. They all had little effective defence against attack by fighters, and none against flak. Aircrew knew they were sitting ducks, there was little they could do to improve their chances of survival.

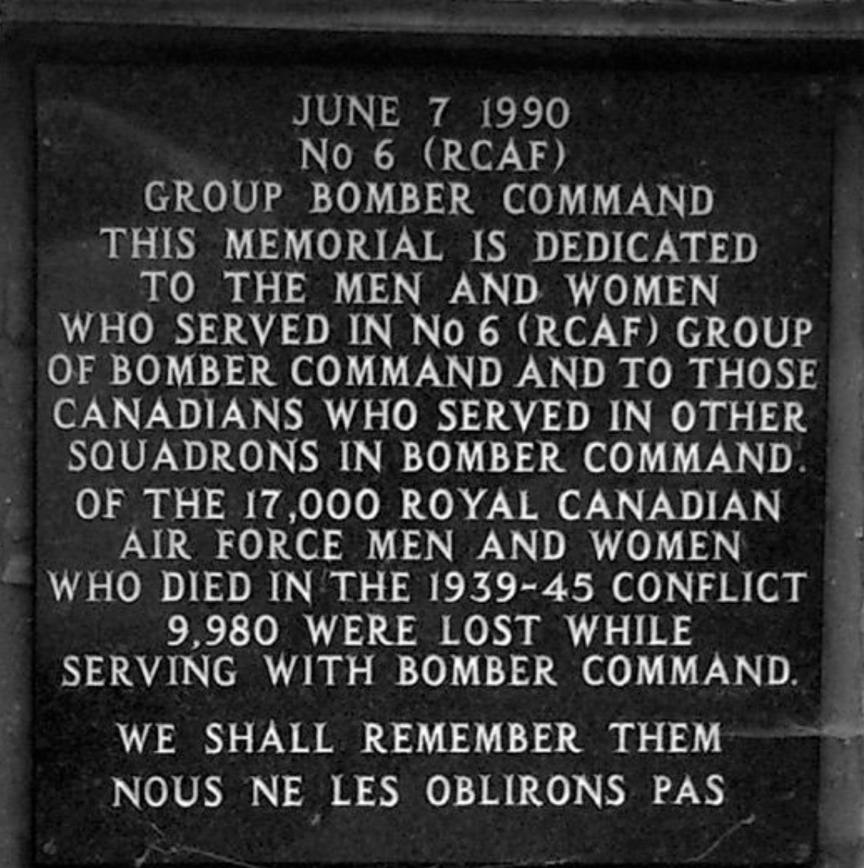

The bomber squadrons flew from first day of the Second World War in 1939 until the last day in 1945, over a third of a million sorties, nearly 9,000 aircraft destroyed by enemy defences or lost in accidents, over 50,000 airmen killed, men from the UK and every Empire and Allied country, plus the many taken prisoner of war and/or wounded.

Just the Canadian casualties included 13,589 airmen killed, 1,889 listed as missing, 2,290 taken PoW, 3,054 injured or wounded. They were lost from the 131,000 aircrew Canada contributed to Britain's war effort, and they were all volunteers, not conscripted, young men regarded as the best of that Canadian generation.

Chapter 2

Canada

The many countries of the British Empire joined the 1939-45 war effort in large numbers; there was a deep-seated loyalty to the 'parent' or mother-country that seems surprising today. The so-called Dominions, Australia, Canada and New Zealand, were the biggest contributors to the Allied forces fighting Germany until the United States of America entered the war. Pilots and others who had escaped from Poland, France and other countries over-run by Germany also joined Britain's war effort, serving in Royal Air Force squadrons.

Canada's involvement was substantial and generous, in money, material and men. The army element started early in the war, with Canadian regiments involved in the British Expeditionary Force and the famous 'small boats' rescue of its survivors from the Dunkirk beaches in May 1940. Canadian regiments were chosen for the ill-fated attempt to capture Dieppe in 1942, where less than half of nearly 5,000 Canadian troops got back to Britain.

The bomber element of Canada's war effort was slower to evolve. Canadian airmen were included in some RAF fighter squadrons from the early days.

There were British air training schools in Canada producing many pilots, but how to use them in the war effort was only worked out with difficulty. The Air Ministry wanted Canadian pilots to continue to be absorbed into the RAF without national distinction; some Canadians in Britain agreed, others didn't. Ottawa's position on how Canadian servicemen should be involved in the air-war seems overly deferential and 'junior partnership' today, but on occasions it took a firm line - only for Canadian officials then to relent when taking their government's messages to Britain after viewing the war damage in London. One wrote in November 1940 of his shock at seeing:

"...entire blocks of flats and other dwellings... smashed to rubble, and the air-raid wardens helped the homeless hundreds in trying to salvage a few pitiful remains or recover the bodies of their loved ones."

A fellow-feeling for the plight of Britain is also evident in another official's reminder to his colleagues that after little over a year of war Britain was almost bankrupt, having to liquidate UK bonds and other holdings overseas. But between British and Canadian there were also cultural differences, in the ingrained attitudes to authority:

"To the traditional English mind, leadership was more a function of style than competence, and men had to be the 'right type'... Canadians preferred the more functional approach of the Americans, who related rank to the job done."

There was an Air Ministry/RAF bias against the more egalitarian, less deferential Canadian servicemen; it didn't help that senior officers tended to refer to Canadians as "colonials" and to the various Commonwealth forces collectively as "coloureds". But beyond the sense of English entitlement, there was a real fear of "splitting the Empire" by giving the Canadians separate roles and structures within the combined war effort.

The cultural divide was there not just in attitudes and manners, but in titles too - the British commander of the Royal Air Force was Sir Charles Portal, in charge of Bomber Command was Sir Arthur Harris, the latter's deputy was Sir Robert Saundby. Although there were many Brits in senior positions who had carried over no civilian titles, there were enough Sirs, Lords and Honourables in the British armed forces in the 1940s to convey a British assumption of superiority which cannot have helped cooperation, cohesion and mutual understanding among the Allies. And not just the British love of titles - my uncle Jack in the army, the Royal Scots Greys, was commanded by Sir Ranulph Twistleton-Wykeham-Fiennes; a pity that the quality of British military material did not match the fine titles and names; the British tanks used in north Africa were vulnerable to German 88mm guns, and my Uncle Jack was killed in his tank in 1942.

The Canadian government felt it should retain some control over its servicemen, and that it had some responsibility for them such as being able to inform their families when injuries or fatalities occurred; after all, it paid their wages, accommodation, the aircraft fuel and explosives, and provided all their equipment. Many of the aircraft, Wellingtons and later Lancasters, were produced in Canada. The Air Ministry agreed to 25 Canadian-staffed squadrons but wanted no higher Canadian structure than squadron, with the many more Canadian aircrew available being dispersed throughout the RAF. However, what developed was different.

The Canadian contribution to Britain's war effort was estimated to be $3 billion, plus lives lost and many others wounded, missing or prisoners of war. An official history, The Crucible of War 1939-1945, provides much information on the RCAF, as reviewed and quoted here; see sources at the end of Chapter 11.

Chapter 3

Yorkshire

In North Yorkshire, the Vale of York became the base for the Royal Canadian Air Force, Bomber Command's new 6 Group, when 'Canadianisation' of staffing and organisation of its contribution to the air-war had became inevitable; in effect, Canada had its own, Britain-based, air force and its own command structure within Bomber Command. Bomber Command's RAF 4 Group was already established in Yorkshire, to the south of York.

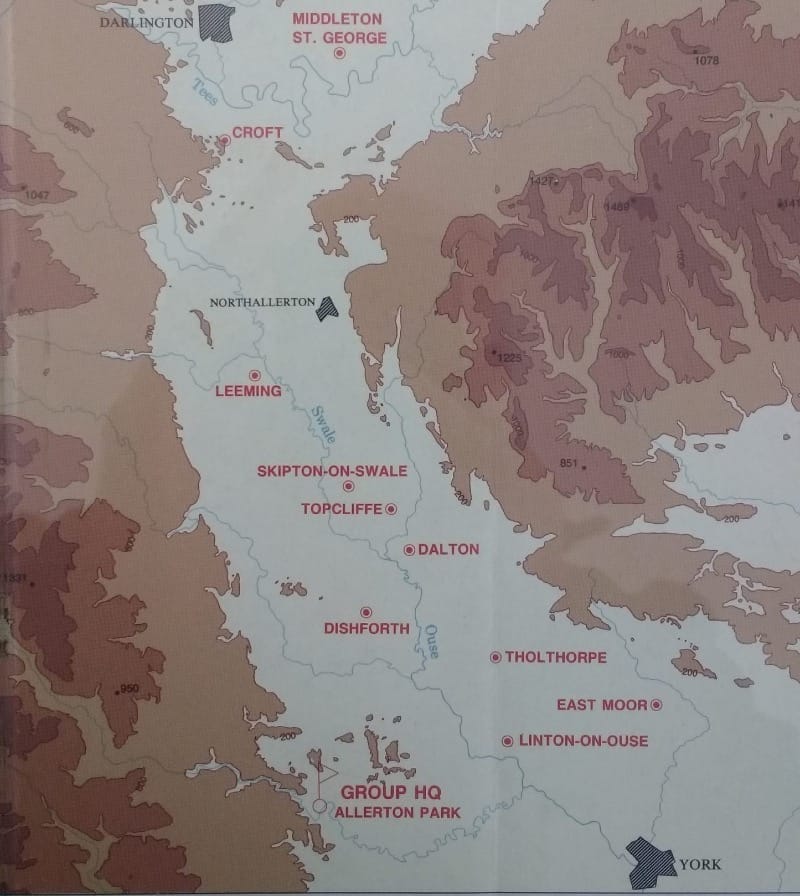

No. 6 Group officially started in January 1943, with its headquarters previously set up at Allerton Hall near Knaresborough, and operational bases at Linton-on-Ouse, East Moor, Tholthorpe, Disforth, Dalton, Topcliffe, Skipton-on-Swale, Leeming, Croft and Middleton St George; some, such as Tholthorpe, were still being upgraded to take 'heavies', four-engined bombers such as the Stirling, Halifax and Lancaster.

The Vale of York extends northwards into County Durham, where some of the 6 Group bases were located. There were RAF airbases (Dishforth and Linton) but no other bomber group was located there so the Vale was available for siting of the new RCAF 6 Group. Being in northern England, it had disadvantages - flying distances to German-held Europe were longer and weather conditions were worse than further south. The Vale is quite a confined area, long north-south but narrow, only about 20 miles across; hills of around 2,000 feet to the east and west were hazardous for aircraft in bad weather and especially for damaged aircraft returning at night, and there were also many training accidents in poor visibility; fogs from the North Sea were common.

Sir Arthur Harris, in charge of Bomber Command, admitted later that the Canadians were "unfortunately placed geographically", with too many bases overlapping in a narrow, difficult area, close to key north-south rail and road links, and close to villages and towns.

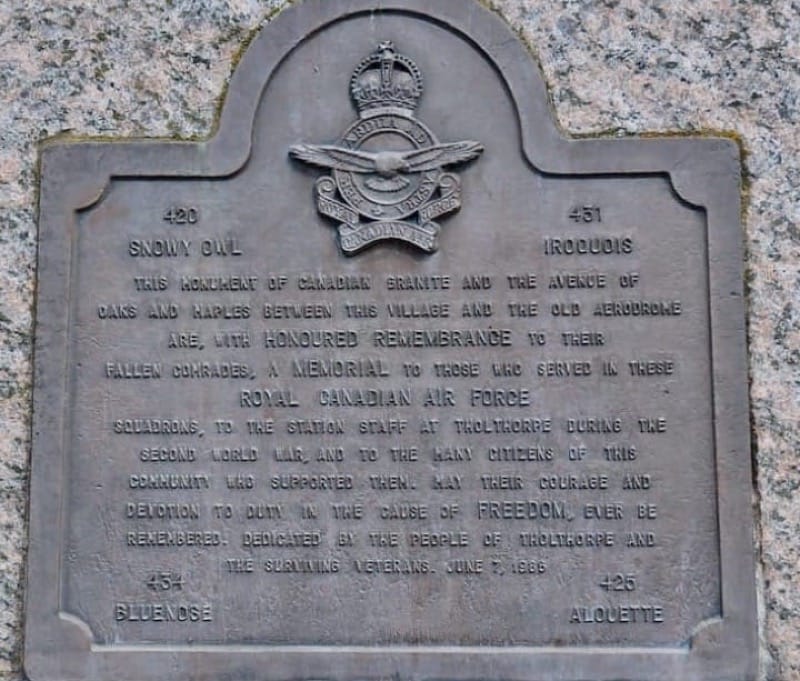

When the RCAF 6 Group was created several existing Canadian squadrons were transferred into it. RCAF squadrons added names to their numbers: Squadron 405 was known as Vancouver, and there was 408 Goose Squadron, 420 Snowy Owl, 424 Tiger, and so on; perhaps a case of Canadian servicemen taking ownership and comfort by adding reminders of their distant homeland.

Canadianisation included recognition of the French Canadians enlisted, and there was the French Canadian Squadron 425, named Alouette (Lark), which my father was assigned to; this was created in June 1942 and included in 6 Group with others in January 1943. Corporal Doucet was groundcrew, based at Dishforth, but later deployed to the Mediterranean theatre of war with 425 and two other squadrons, then returned to Dishforth, East Moor and later Tholthorpe (see Chapters 5 and 6). Already in existence were two so-called Free French squadrons, in 4 Group and based at Elvington; these were aircrew who had escaped from France as it was invaded by German forces in 1940.

The first commander of 6 Group RCAF was G. E. Brookes, a 47 year-old veteran of the First World War, previously in charge of a training command in Canada. He and his HQ staff were said to have brought little flying or organisational experience to the new group; he attended meetings of group commanders with little or nothing prepared in the way of plans and maps, while others arrived with much to propose and contribute; perhaps sensibly, as the new boy, he was in listening and learning mode. But he also had a reputation for holding aircrews on standby (briefed, kitted up, tensed up) for hours in the evenings when very bad weather reports prevented flying, in the hope that conditions would improve at the last minute - so, very keen to impress, but at a cost to aircrews' stamina and morale.

Bomber Command dictated the target, date and scale of bombing operations but left each group to decide the many operational details; in this, Brookes, from his diaries, seems to have engaged little, nor in analysing and learning from results of raids. For example, of a 28/29 August 1943 attack on Nuremberg he noted only "Our lads had a good crack at them last night, and caught a good crack themselves". In fact, 34% of his Wellington aircraft and aircrews were lost on that raid. In December Sir Arthur Harris, newly in charge of Bomber Command, was privately "alarmed at the prospects" of 6 Group under Brookes' command.

In the official history of the RCAF, Brookes was described as having "a singular detachment from the hard realities of the bomber war".

No. 6 Group's performance was worse than other Groups in early 1943. This could be explained by the recent influx of newly graduated aircrew and groundcrew straight from training in Canada, but so many errors were unacceptable, and serious; for example, in January one squadron could not be bombed-up for that night's mission because the armament office couldn't find the bombs; an armourer removed guns from a turret while they were still loaded; incendiary bombs were loaded with the jettison bars armed with the result that when the electrical circuits were closed the incendiaries fell on the runway. While it was accepted that inexperience might explain such mistakes and both servicing and bombing peformances would improve, and losses reduce, with time, Harris called for more analysis. No. 6 Group was compared with 4 Group which was stationed nearby and also flew Wellingtons and Halifaxes; 6 Group's early return rate was worse, mainly due to problems with oxygen supplies, guns, turrets, and icing; it was thought groundcrew maintaining the aircraft had not benefited from their on-base training while with 4 Group before 6 Group was formed. Also, training units in Britain commented that navigators graduating from the British Commonwealth training programme in Canada were slow at map-reading, astro-navigation and chart work, and that new pilots had little understanding of navigation.

"Lower morale" was also posited as a reason for 6 Group's poor performance in 1943. George Brookes blamed the "combing out" of the best crews for deployment to the Mediterranean; this suggests a very wide range of ability or diligence in 6 Group, but that was not explored further.

Local weather conditions, and Bomber Command's determination to fly in all but absolutely impossible weather, may have been more responsible for poor performance and aircraft losses than was accepted at the time. In the Vale of York and the wider area of hills and moorland, weather can be very unpredictable, as two men searching in later years for a war-time crash site recorded:

"...we left in bright sunshine with the odd spot of rain... the weather turned really foul, the wind became gale force, the snow became a blizzard and visibility was down to 50 yards and below..."

That was in April, not winter.

Concern about the RCAF 6 Group persisted despite some improvements. On the 2/3 August 1943 raid on Hamburg the early return rate was high for Bomber Command at an overall 42%, but for 6 Group it was 59%. And of the 43 RCAF crew that returned early from Hamburg only two had made any attempt to find and bomb an alternative target; as before, the possibility was raised of "a less determined attempt to get over enemy territory than some of the other Groups." However this was also Harris's verdict on all the Groups involved in a 700-strong raid on Hanover in September: "most crews failed to make the slightest attempt to approach the target on the course set down..." In the same month, there were still complaints about "lack of adequately trained personnel... poor servicing of equipment and... faults" in 6 Group.

New Year 1944 was 6 Group's first birthday, grown from eight to 13 squadrons. Although losses were still higher than most bomber groups, the difference was narrowing. Maintenance and servicing of aircraft had improved. By the early months of 1944, 6 Group had become less of a concern to Harris and the Air Ministry; although losses were still high they were no longer the worst in Bomber Command and part-explained by the number of Halifax IIs and Vs (inferior versions of this heavy bomber) in the group. In fact, "experienced Canadian Halifax squadrons had fared better than the No. 4 Group average, and the Lancaster [RCAF] squadrons were doing better than" those in 3 Group despite the longer distances to target and often worse weather in the Vale of York.

Having made these achievements in little more than a year, with a new bomber group in a new location and inexperienced personnel, Air Vice-Marshal Brookes was exhausted; he returned home to Canada and retired the following November. He was replaced in February 1944 by another veteran of the First World War, C. M. McEwen, then station commander at Linton-on-Ouse. McEwen prioritised improvements in training, in defensive tactics by training with British fighters, in navigation and in discipline. By September 1944, RCAF 6 Group had as good an operational record as any.

The RAF and Air Ministry implemented agreements only slowly with regard to the contributions Canada was making to the war effort. This was not entirely due to bureaucratic obstruction; there was a genuine reluctance to breaking up established teams in air and groundcrew, and some Canadians preferred to remain in mixed-nationality RAF units.

In September 1941 there were 4,500 Canadian aircrew in Britain but less than 500 in RCAF squadrons. Formation of the 25 RCAF squadrons agreed by the Air Ministry was slow, with 'excess' pilots and others remaining dispersed through RAF units, but eventually by 1944 there were 54 RCAF squadrons. There remained many Canadians still in the RAF, and RCAF squadrons included a small number of other nationalities; flight engineers in RCAF squadrons were British.

Gradually more women had roles in 6 Group; by May 1945 there were 567 female officers and 372 other ranks at the Allerton Park HQ alone, and others at the squadron bases in admin and groundcrew roles. By April 1943 women were permitted to serve as wireless operators, parachute riggers, meteorologists, instrument mechanics and to interpret reconnaissance and bombing photographs.

Women were not permitted to take on combat roles, but many carried out the vital job of flying aircraft to and from operational and training bases. Being expected to fly (usually unaccompanied) many types of aircraft at short notice, albeit short distances usually in daylight, they must have been very capable pilots who, but for the conventions or prejudices of the time, could have been involved operationally.

A navigator with 425 Alouette Squadron recalled, many years later in a commemorative newsletter, going on a bombing raid to Turin in November 1942 (prior to the creation of 6 Group). The crew was apprehensive about flying over the Alps with a bomb-laden, fuelled-up aircraft, but reached the target where flak was heavy. Crossing back over the Alps, the aircraft started to vibrate, the cabin lights went out, and it became hard to control. On reduced revs they eventually reached Dishforth, but the Air Traffic Control signalled red - not to land, to 'go around'. The pilot told the crew to bail out which they refused to do, and he approached to land the ailing aircraft only to get another red/go around from the ATC. He ignored this and landed successfully. The Bomber Command War Diaries record four raids on Turin in November 1942; the list of the squadrons and groups involved is not complete, and those named do not include 425 Squadron or 6 Group RCAF. The Diaries are reviewed and quoted in this article, with critique and discussion in later chapters.

A Bomber Command squadron included between 20 and 30 aircraft, organised into two or three 'flights'; numbers changed during the course of the war. Wellington two-engine medium bombers had crews of five or six; Halifax four-engined bombers had crews of seven, with numbers and in-flight roles changing during the war. Therefore, a squadron might have around 200 aircrew personnel.

Flak was the name given to anti-aircraft fire from ground-based artillery, also called ack-ack. Germany developed formidable artillery for this purpose, some of it rail-based for movement to defend different targets; it was used in dense systems allied with searchlights. Much of Bomber Command losses of aircraft and crew were caused by flak:

"The most alarming factor of the German defences was undoubtedly the searchlights. They had master beams, radar controlled, during the preliminary search ...once caught, every searchlight within range would fix you and wriggle and squirm as you might, you couldn't shake them off. Then the guns joined in and filled the apex of the cone with bursts: it was a terrifying thing... the sequel was a small flame, burning bright as the aircraft fell towards the ground... Everyone dreaded being coned... the only sensible thing to do was to head away... by the shortest route..."

Chapter 4

A Fragment...

The fragment is of my father. His four years' service in the RCAF in Yorkshire during the Second Word War was a fragment of his life, and a fragment is what I know of him. He was 22 when enlisting in the RCAF, in Montreal, in July 1940; he had married the previous February.

Over half a century later I asked my father why he'd enlisted; he said he was out of work, there were no jobs in the impoverished, francophone part of Montreal.

British Commonwealth Air Training Units in Canada (also in Australia) started in 1940/41; the initial stage was to stream candidates for aircrew or groundcrew, and then to specialisations such as navigation, wireless operator and, of course, pilot. There was one training unit in Montreal which he may well have attended before deployment to Britain. I have not discovered when he (with others) arrived in the UK, nor specifically in Yorkshire, but he was there by 1942.

For a young man from a poor family, with no prospect of work or travel, there may well have been a sense of adventure and purpose in being shipped, with other young men, to Britain, and a wage being paid, some of which he could have sent back to his wife; they had no children together until post-war.

For all the novelty of travel, companionship and a paid job, the man who would become my francophone father arrived into a world which was not only foreign in language, behaviour and surroundings, but also one of darkness, fear and uncertainty, for everyone. First of all they arrived at Liverpool or Greenock - blitzed harbours and buildings with windows boarded, blacked-out or taped, sandbags everywhere, streets deserted. Then by train and bus through countryside with none of the usual bustle and traffic of ordinary peace-time life. The blackout regulations meant that streets and buildings were in near-total darkness at night, air raid sirens sounded regularly prompting a rush to shelters, the atmosphere was tense, uncertain - a German invasion had been feared in 1940, children from cities were evacuated to the countryside (in 1939, and again later), one massive defeat had already been suffered at Dunkirk, and by 1941/42 there had been little sign that the Allies could defeat German forces.

Ordinary life had stopped: there were few men around, almost everything was rationed, queues of women waited outside shops, and there was the constant scramble of a country ill-prepared for war having to create new military bases, produce weaponry and accommodate thousands of servicemen including many from other countries. In its many parts, putting Britain on a war footing was the largest civil engineering project the country had ever known. In the southern and eastern England many new airstrips had been created on farmland, followed elsewhere by more airstrips and their many associated buildings, hangers, fuel stores, bomb dumps, all accompanied by the movement and housing of thousands of personnel.

The organisation and logistics of this country fighting a major war, for which it had been unprepared, were enormous, an on-going process, and had changed life considerably.

For young Canadians arriving in Britain suddenly war was not something happening far away. It was a constant presence in Yorkshire, as in many parts of the country hosting airfields. War was an inescapable presence, from the density of airfields - there were eight airfields within ten miles of Linton - to their constant activity day and night. One resident remembered that "... the sky over Wetherby was black with aircraft on their outward journey". Some crashed soon after take-off, in darkness and often in bad weather, such as a Halifax bomber from 426 RCAF squadron whose engines cut out and, fully loaded, fell onto farmland beside the main A1 road and exploded.

The sound of bombers returning disturbed many nights, and people learnt to detect the different sound of some limping home damaged, flying low in the darkness, with one or more failed engines, or short of fuel, with exhausted and sometimes injured crews. Not all of them made it, such as a Stirling heavy bomber which crashed into a street in Tockwith village, hitting 17 houses, bouncing along the rooftops until it broke up, its burning fuel setting many of them alight. Many other examples of how war came as bolts from the blue, or from the night sky, to suddenly bring death and destruction to civilian life in Yorkshire, countryside and town, are given in specialist local publications. One of the many was on 22 October 1943, when a Halifax from 427 Lion Squadron returning from a raid on Kassel lost power from one engine, then a second engine, lost height and crashed into a wood by the railway line at Newton Kyne, exploding on impact; a local woman wrote:

"It was a terrible sight with ammunition going off all the time... all the men of the village ran to the spot, alas no one could get near. All the crew perished in the flames..."

Training flights could disturb the daylight hours, and also carried a risk; a mixed RAF and RCAF crew in training encountered a fire in the port-outer engine of their Halifax bomber at only 1,000 feet (too low to bale out), and crashed onto a golf course; the crew, all killed, were aged 18 to 24 years;. Years later a local doctor wrote about this:

"as a boy I can well remember the plane with four engines coming low over our garden, and I noticed there were flames coming from one of the engines. I called my mother... it disappeared over the trees. A few seconds later there was a flash... a loud boom and a tremor of the ground."

There were also deadly 'intruders' - German fighters attacking the Yorkshire airbases during the day, and attacking British aircraft returning at night from bombing operations, often aircraft which were struggling home damaged and with exhausted or injured crews. One intruder machine-gunned the York-London train on the main line running alongside an airbase. Three German aircraft attacked Linton in May 1941, killing the newly arrived station commander, 12 other personnel and injuring 13 more. Another German intruder the previous month had shot down two Blenheims just airborne, another on the runway; later (and surprisingly?) a training flight was sent up and that aircraft, a Defiant, was shot down over Thorp Arch. Two months later, a German night-fighter crashed into a Wellington bomber, killing the crew of both aircraft. Three commanding officers of 424 Tiger Squadron at Skipton were killed in a nine-month period. Driffield was out of action for nearly six months in 1940 due to German intruder raids in which 12 personnel and a civilian were killed, ten Whitley bombers and many buildings destroyed. There were many more intruder incidents. The Yorkshire airbases were close to, and named after, villages and towns - even when local people did not become casualties, ordinary life day-to-day was surely much affected by terrifying events like these so close by.

In addition to the operational and training airfields there were decoy airbases to try to draw off intruders, and an emergency landing base at Carnaby used by both 4 Group and 6 Group.

York city was blitzed by German bombers ten times between 1940 and 1942, with the railway station destroyed, a church gutted and much housing destroyed; in one raid 151 people were killed, mostly civilians, including six German aircrew. Hull was also bombed. Harrogate escaped serious German attention, being bombed only once, near the Majestic Hotel, with damage to nearby houses and buildings.

And yet, for all this, they were young men abroad, there was an excitement. Off-duty they escaped from their airbases to nearby pubs, and often to York where Betty's was a favourite; they called it 'The Dive', a bar in the basement below Betty's tearooms. Canadians and other servicemen scratched their names into the big mirror behind the bar. For some of the aircrew, burnt or shot to pieces over Germany, that was all would remain of them.

Or they went to Harrogate 20 miles to the west, a spa town made popular in Victorian times with many fine buildings, grand hotels with dining rooms and bars. One of the few things my father said to me, with a wistful smile on his face, was "oh, I remember Harrogate..."

With the uncertainty of war, young men away from home must have revelled in the camaraderie and release from the stresses and exhaustion of sending bombers night after night towards Germany, knowing many would not return, friends' faces missing at breakfast next morning.

Harrogate General Hospital (since demolished) on Knaresborough Road was where many of the injured air and groundcrew were taken; extra buildings were put up to care for them. Those who died, in hospital, on the airfields or surrounding countryside, were buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetary at Stonefall, Harrogate. Of the 998 airmen buried there, two-thirds were Canadians. From the Commission's website:

"The digging of the graves, which in 1944 was more than forty a week on occasions, fell to Mr Linfoot, Cemetery Superintendent from Harrogate Borough Council, who struggled to find the labour for this task due to most able-bodied men serving in the armed forces.... members of the Royal Canadian Air Force made up around two thirds of the casualties at Stonefall... Alongside the Canadians a significant number of 6 Group personnel were from the Royal Australian Air Force and the Royal New Zealand Air Force as well as RAF as is reflected in the casualties at the site."

Betty's cafe in St Helen's Square, York, is still there. When I last visited the mirror with Canadian and other aircrews' names was mounted on a wall in a basement lobby; it had been fractured into several pieces by an incendiary bomb falling nearby. This is from a memoir and war-time diary by one of the servicemen who frequented Betty's Bar:

"A day and evening in York was a real pleasure and break from our flying Duties. Betty’s Bar seems to be an unofficial Headquarters for Air Crew. It was a Meeting Place and to remain a short time one is bound to meet old friends from other Squadrons... Sadly, the news is very bad as we hear of Heavy Losses throughout the Group. The Squadrons in early 1944 apparently are taking a terrific beating in the Battle of Berlin. – We don’t indulge in much discussion on Losses only a remark Now & Then. ‘Bill has gone for a Burton on Mannheim’, – ‘John crashed into a hill on return from Le Mans’ and so on. The names spoken are many. – Can one finish a tour of ops?”

Chapter 5

To the Mediterranean

Soon after 6 Group was created, three of the RCAF squadrons (nos. 420, 424 and 425 - in which my father was a fitter in the groundcrew) were formed into Wing 331 and sent, in May 1943, to Tunisia. This was to support the planned Allied invasion of Sicily and Italy. The intended three month deployment extended to six months, which incidentally saved these squadrons from the heavy Bomber Command losses incurred over the Ruhr from May to July 1943 and the so-called Battle of Berlin from November.

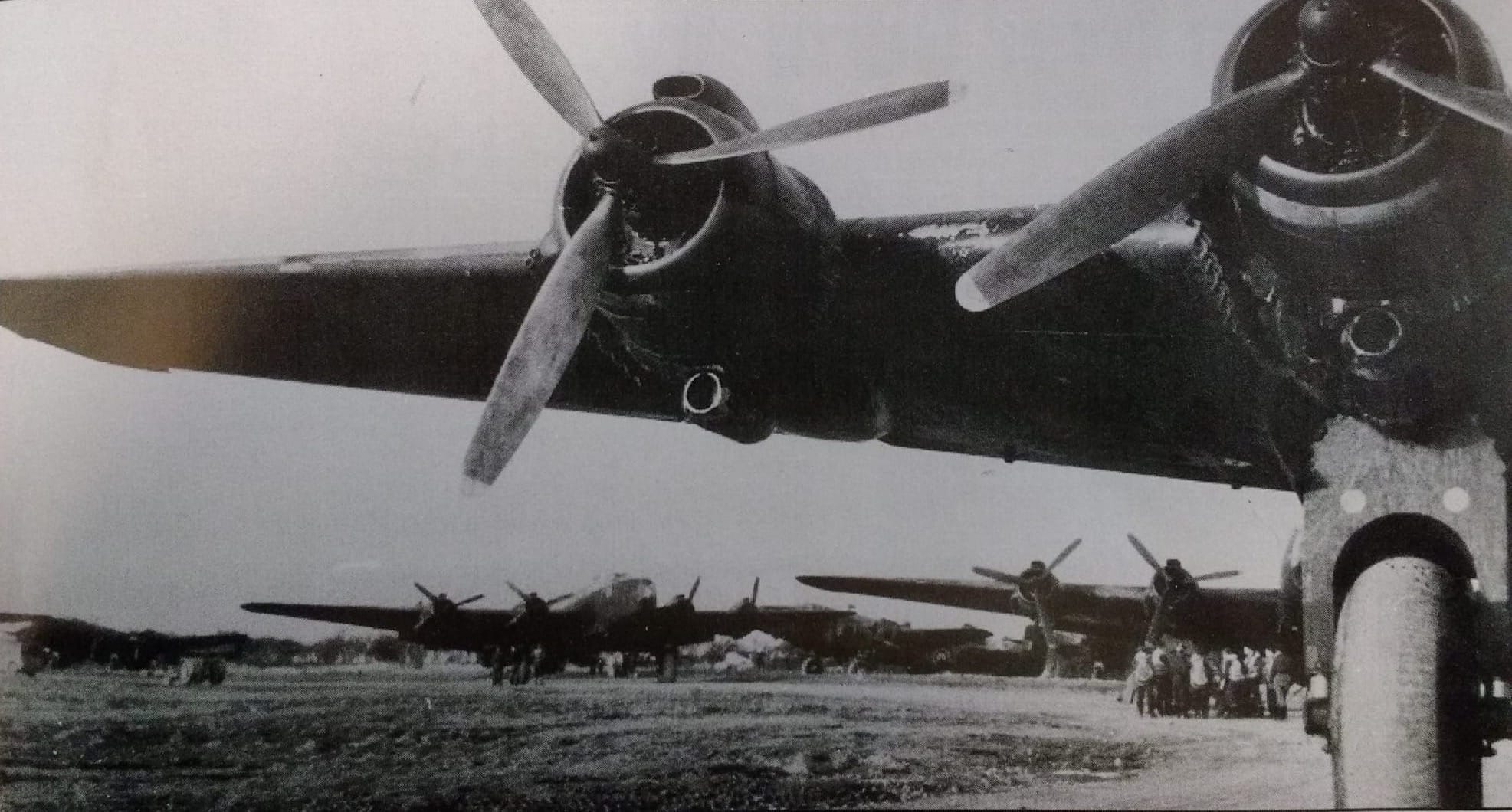

Both air and groundcrew of the three squadrons were transferred, equipped with Wellington Xs (the latest, improved version of this two-engine medium bomber, manufactured in Canada) plus tropical kit and supplies. Such was the dominance of German military force across Europe that three of the aircraft were attacked and lost (with their aircrews, probably more than 15 men) en route to Tunisia despite taking a circuitous route over the Atlantic. Groundcrew and others sailed from Liverpool on 18 May 1943.

On arrival, there seemed to be a comedy of errors. Mediterranean Air Command had made no preparations and the best sites for airstrips had already been taken by US forces. Three less favourable sites were found; bases (buildings, latrines, roads, landing strips, servicing areas, bomb and fuel dumps, etc) had to be created in high summer temperatures, then a tropical rainstorm waterlogged landing surfaces. A radio message to halt 424 Squadron flying in was lost "due to the poor signals communication" and they landed in heavy mud. Working and living conditions were harsh. The much delayed and much needed showering facility collapsed after half an hour of use.

But overall the three RCAF squadrons were reported to have performed well, in operations quite different to those over northern Europe: instead of high-altitude area bombing, targets were enemy airfields, supply routes and, later, troop concentrations counter-attacking the Allied landing at Salerno. Summer flying conditions helped, as did the thinness of flak and night-fighter opposition (except over the Straits of Messinia and, later in the Italian campaign, over heavily defended targets such as Naples). There were exceptions: on 424 Squadron's first mission, one aircraft dropped its bomb on take-off did not notice and continued, another burst a tire and dropped its bomb and the next two took off not having noticed; four more aircraft were not bombed-up in time - this was blamed on the armourers having only recently arrived and being inexperienced. The next night two aircraft were lost in action. Within a month, 35 aircrew in the Wing had become casualties. Dysentry, diarrhoea and malaria affected many despite inoculations, and food supplies were initially poor.

Groundcrew had the extra essential jobs of removing sand and dust from guns, fuel tanks and bomb bay doors. But maintenance standards were said to be good, and availability of serviced aircraft was high. US commanders praised the Wing's efforts, notably for 424 Squadron's attack on an airfield near Salerno destroying 40 enemy aircraft, and 420's and 425's pounding of enemy forces around Enna. By mid July, 353 sorties on 12 nights had been flown.

However, Allied forces including the RCAF Wing failed to prevent 40,000 German troops and 62,000 Italians escaping from Sicily to bolster enemy forces in Italy; the RCAF Wing 331 lost five aircraft and 25 aircrew in the effort.

Wing 331's three-month deployment was extended and operations supporting the Allied landing in Italy continued. Against a strong German counter-attack towards Salerno, the Wing flew 43 sorties dropping 82 tons of bombs on three German divisions, and similarly against other targets on later nights. RAF commander Sir Charles Portal noted:

"...the exceptionally good work done by the Canadian Wellington Wing in the Mediterranean... the scale of the effort in relation to the size of force has probably been higher than... anywhere in the past and included operations on 78 of 80 nights, with a nightly average of 69 sorties."

Sir Arthur Tedder added that the three RCAF squadrons "...may well have saved the day".

When their deployment ended these squadrons left their aircraft behind and sailed to Liverpool, arriving in snow and rain on 6/7 November 1943. They travelled on to their bases in Yorkshire, took some leave, re-kitted, and re-trained to fly and maintain Halifax IIIs; these aircraft were regarded as much better than other versions of the Halifax four-engined bombers also flown in 6 Group. In December 1943 the groundcrew of 425 Alouette squadron was moved to Tholthorpe to train on the Halifaxes; I have the Movement Order which includes my father, identified as R66733 LAC (Leading Aircraftman) Doucet, J.C.E. (the E. must be a typo - that's his correct service number as on other documents, who was one of the groundcrew, with mainly francophone surnames).

A sortie refers to one operational flight of one aircraft

The RCAF's Mediterranean mid-1943 operations are described here quite fully because it summarises the only detailed account I have found of my father's 425 Squadron 'at work'. It is not included in the Diaries.

The December 1943 Movement Order is unclear, in that it refers to groundcrew being moved from Dishforth to Tholthorpe, and both from and to Linton and East Moor. As I understand it, returning groundcrew (over 300 men) of 425 Squadron arrived initially at Dishforth, Linton and East Moor, and were then transferred to re-form at Tholthorpe.

Chapter 6

Tholthorpe

Ten miles north-west of York, Tholthorpe was a grass-runway airbase at the start of the war, and in only light use initially; it was closed for concreting to cope with winter operations and heavy bombers. Due to the war-time lack of labour and materials this was not completed until June 1943 when it was assigned to 6 Group RCAF and occupied by 434 Bluenose Squadron and 431 Iroquis Squadron, both operating Halifaxes. These two squadrons moved to Croft, and at the start of 1944 Tholthorpe became the base for 425 Alouette Squadron and 420 Snowy Owl Squadron, newly returned from the Mediterranean and re-training for Halifax IIIs.

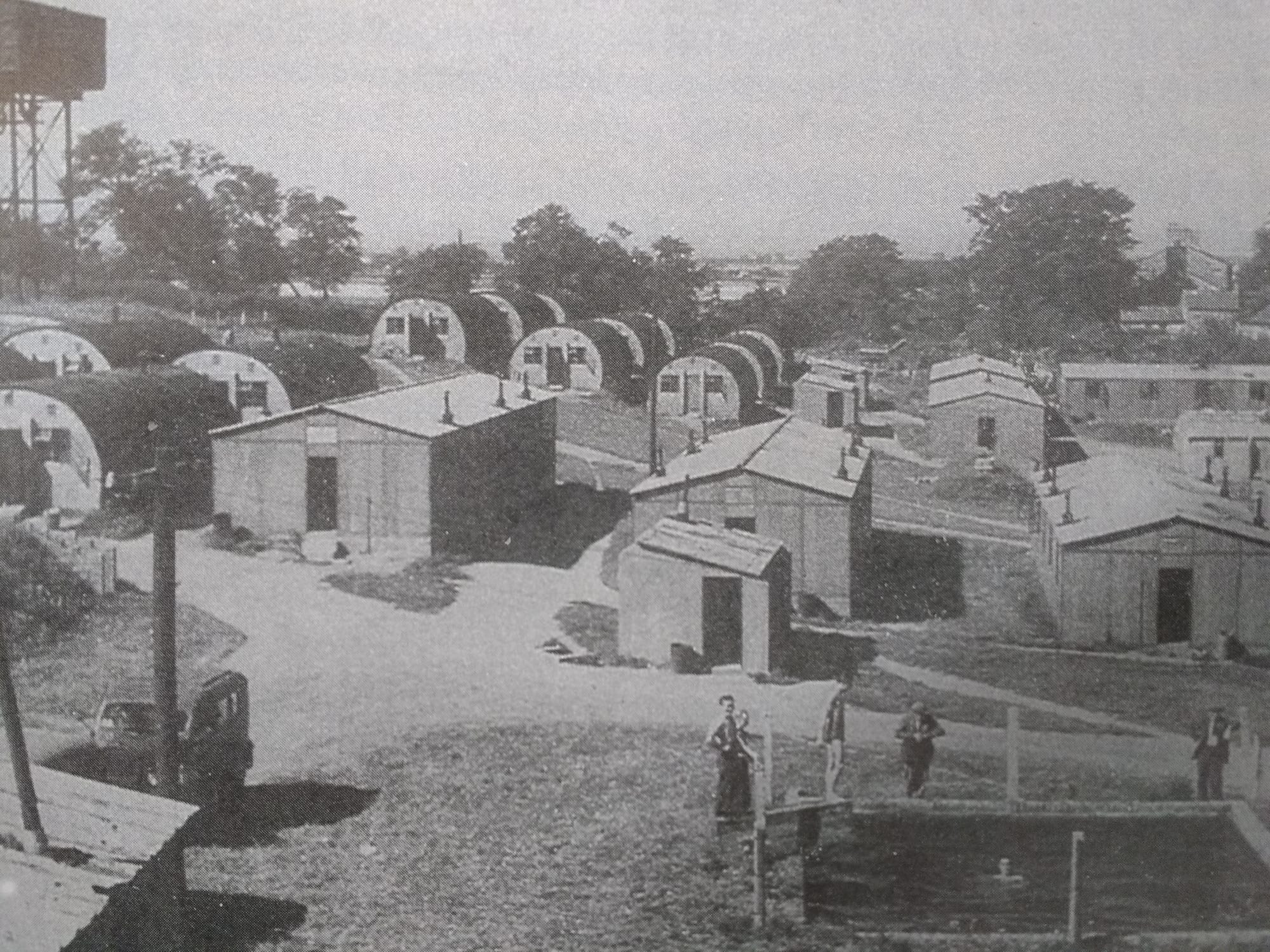

Tholthorpe became one of the busiest bomber bases in Yorkshire until the end of the war, but like many of the Yorkshire airbases conditions were very basic; over 1,000 personnel were based there, some billeted in the village from which it took its name, many others in hastily constructed concrete-floored, corrugated metal-roofed bunkhouses. One of the storehouses on High Farm was used as a hospital and mortuary. Although runways and the perimeter track were concreted, everywhere else there were duckboards over a sea of mud in the (mostly) rainy weather. During take-off for a raid on Leipzig three Halifaxes bogged down in heavy mud, blocking access to the main runway. This photograph shows a typical accommodation and staff buildings on a Yorkshire bomber base.

Villagers and Canadians socialised of course, and Tholthorpe villagers saw the dire effects of war constantly; some young men they knew and had spent time with failed to return from almost every night's bombing raid, and sometimes death and destruction hit the village directly. On one occasion a Halifax soon after take-off crashed into a farmhouse, killing all the crew; a villager who was a child at the time remembered later that:

"We ran to the farm from school at lunchtime. I wish we hadn't. The stench of burning flesh was terrible. Thankfully no civilians were killed."

In January and February 1944, before the two Tholthorpe squadrons became operational, 10% of RCAF Halifax IIs and Vs failed to return from just six heavy raids over Germany, an unacceptable loss rate; the five RCAF squadrons involved were diverted to the lighter duties of minelaying (termed 'Gardening').

The Mediterranean deployment May-November 1943 had spared the two Tholthorpe squadrons the heavy losses sustained by Bomber Command over Germany in 1943, and may also have resulted in them being equipped with the best Halifax variant upon their return; the earlier Halifax IIs and Vs were withdrawn from all further operations over Germany after disastrous losses in the 19/20 February 1944 800-aircraft raid on Leipzig. Out of 255 Halifaxes involved, 34 were lost.

The two RCAF squadrons at Tholthorpe were also lucky to avoid the heavy losses in the 30/31 March 1944 raid over Nuremberg - the worst night of the war for Bomber Command, when 95 aircraft were lost. Only one aircraft from Tholthorpe's squadrons failed to return, a Halifax from 425 Squadron piloted by Flight Lieutenant John Taylor from Winnipeg.

Bomber Command's focus changed from night-bombing of German cities to preparation for the Allied landings in Europe which took place in June 1944, with the Tholthorpe squadrons involved, targeting enemy defences and communications in northern France, and then supporting Allied ground forces there.

No. 425 Alouette Squadron had a good record overall. Flying Wellingtons initially it carried out 28 bombing and 11 minelaying operations, losing eight aircraft in 347 sorties; flying Halifaxes it carried out 162 bombing raids, losing 28 Halifaxes in 2,445 sorties, loss rates of 2.3% and 1.1% respectively. But numbers don't tell the whole, human story, and 'lost' and 'losing' start to sound like euphemisms.

Raids when the war was almost over, on the night of 5/6 March 1945 to assist the Russian advances into Germany incurred heavy losses for the Tholthorpe squadrons before they got anywhere near enemy territory. And what happened indicates the hazardous, unpredictable conditions these young men were exposed to throughout the war years: nine RCAF 6 Group bombers crashed on take-off due to icy conditions, four were from Tholthorpe. Two of 420 Squadron's Halifaxes stalled due to heavy ice build-up on the airframe and engines, similarly one aircraft from 425 Squadron crashed iced-up, and that squadron lost another in collision with an iced-up Halifax from Linton (which lost three aircraft more due to icing). Most of the aircrews were killed, and some civilians.

One of the aircraft (it is unclear which) fell on York, killing six of the seven crew and five civilians; the fuselage fell in Nunthorpe Grove and one of the engines fell on the grammar school. Then, three more Tholthorpe aircraft from this operation were lost over Germany, and two more crash-landed on their return.

The last Tholthorpe bombing operations were on 22 April 1945 (420 Squadron) against Bremen and 25 April (425 Squadron) against gun batteries on the Frisian islands; the Frisian raid was two weeks before the war ended, and seven aircraft were lost (six of them due to collisions), 28 Canadian and 13 British men killed.

After the German surrender on 8 May, 6 Group squadrons and Bomber Command used their heavy bombers to take supplies to Europe and repatriate thousands of PoWs.

With the war in Europe over, both Tholthorpe Canadian squadrons were allocated to operations being prepared to join the war against Japan which was still underway. These squadrons exchanged their Halifaxes for Lancaster Xs and returned to Canada after several refuelling stops, landing at Dartmouth, close to Halifax in Nova Scotia; 425 Alouette Squadron aircraft left Tholthorpe on 20 June. My father, and presumably other groundcrew, was shipped to Halifax, indicating that these squadrons were re-forming for deployment to the Pacific. However, the Japanese surrender after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought a sudden end to war in the Far East on 2 September 1945, and both squadrons were disbanded. Corporal Doucet was demobilised in Moncton, New Brunswick, on 19 September 1945.

Tholthorpe airbase was not incorporated into the post-war RAF and lay derelict until the 1950s when it reverted to agricultural use, the former control tower solitary and decaying among crops in the fields until it was renovated and converted much later into a dwelling.

A memorial to the four RCAF squadrons that had been based at Tholthorpe was erected with a tribute in French and English to the Canadians who had served there; maple and oak trees, symbolising Canadian and British life were planted leading to the airbase. The memorial was unveiled in 1986 by Air Vice-Marshal Donald Bennett, in a reunion which over 350 Canadian ex-airmen of the Tholthorpe squadrons, relatives and friends attended. One person there was the only survivor from one of the four Tholthorpe Halifaxes that crashed on take-off in icy conditions in March 1945, a wireless operator who parachuted at a low height and was badly injured. A villager, who had helped organise the reunion, said this man "...could remember all their names and just talked to them as though they were alive today". He also visited the graves of his crew at Stonefall Cemetary in Harrogate.

It is a quiet and pleasant English country scene now, beside a tree on the village green, in contrast to the noise, fear and desperation that Bomber Command's night-war brought to Yorkshire.

Minelaying, so-called Gardening, was not necessarily the lighter, safer operation that Bomber Command considered it to be, useful to give new pilots experience before bombing raids over Germany or to give exhausted bomber crews a bit of a breather. One flight engineer based at Leeming later described it as:

"...an extremely critical operation, flying at no more than 500 feet above the sea at night. It called for very accurate navigation... [on one operation] six bombers went out - but we were the only crew to get back to Leeming. The rest either crashed or were shot down."

Conflict with Japan continued after victory was achieved in Europe in May 1945. A year previously, in June 1944, the Canadian government had declined to create any more bomber squadrons because of the continuing high casualties, and instead created three transport squadrons, one in Europe (Squadron 437, used in support of the land battle in Europe and then materials-supply, disbanded in July 1946) and two in southeast Asia (squadrons 435 and 436, formed in India in September 1944). Complete crews were shipped from Canada to India, and almost 600 groundcrew were shipped from Britain to Canada then flown to India. To the RCAF squadrons were added four RAF and eight USAF transport squadrons.

From April 1944 southeast Asia was a priority area for transport capacity

to supply the Fourteenth Army's counter-offensive against Japanese forces in Burma. Airlift was essential because of the mountainous terrain and lack of good roads and airbases, and limited timewise by the monsoon. RCAF squadrons 435 and 436 flew American-built DC47 Dakotas, whose flying characteristics were well-suited to the challenges posed by terrain and weather.

At the outset the air chiefs of staff had been very sceptical about the possibility of maintaining logistical support by air alone for a major ground operation over such long distances in very difficult conditions. They were proved wrong. After the surrender of Japan in September 1945, General Slim concluded that the airlift transport squadrons had:

"contributed to a new kind of warfare... We were the first to maintain large formations in action by air supply and to move standard divisions long distances about the fighting front by air... a new technique that combined mechanized and air-transported brigades in the same divisions.... the largest number of transport aircraft we ever had was much less than would elsewhere have been considered the minimum required... the skill, courage and devotion of the airmen... both in the air and on the ground... we learnt to revise accepted theories and, when worth it, to risk cutting our margins."

On his demobilisation my father's name and service number were given as Corporal Joseph Cleophas Jean DOUCET, R-66733. That is the same as on my birth certificate except that the registrar misheard Jean and wrote John. He and my mother signed my birth certificate on 30 April.

My mother's name was given as Florence Agnes Doucet. In November 1944 she had changed her surname to Doucet by deedpoll, presumably after my father told her he was already married. In fact, he would not have gained the necessary permission to marry, nor to remain in Britain, married or not; wartime regulations were strict about this, probably quite a frequent ocurrence, and only officers had any chance of gaining such permission.

How much contact my mother and he had after the presumed 'I'm married already' conversation in November 1944, I do not know. But enough for him to be at the registry office, with both parents giving the Doucet surname in the following April. And what contact between them before he returned to Canada in September? He was discharged from the RCAF in Moncton, New Brunswick, on 19 September 1945, with the Defence Medal, Canadian Volunteers Service Medal with Clasp and War Medal 1939-45; these are quite standard issue, I think, though the 'clasp' sometimes indicates a more individual achievement. I don't think he was awarded that for clasping my mother and fathering me.

Post-war there was much unemployment in Canada, as there had been pre-war, and this was increased by the rapid closing of war industries. Like many, my father struggled to find work at first. He became known as Cliff or Clifford, and was so named in his 2012 obituary. I wonder if this anglicising of his name started in 1940s Yorkshire, adapting for my mother and local people.

Chapter 7

Home Crashes

The two authoritative accounts of Bomber Command and the RCAF to which this article refers give much detail and commentary on bombing operations, their organisation, performance and losses, and their impact on enemy territory, but far less on Bomber Command's effect on home territory - what it was like for both service personnel and civilians in Britain living on or close to the many airbases. So-called 'home crashes' - flying accidents, both operational and in training - had a major impact on people living in Yorkshire during the war years.

The many airbases of 6 Group north of York, and 4 Group to the south, were close to each other and close to towns and villages from which the bases took their names. Operational aircraft crashing on take-off and landing, and training flights crashing, had an inescapable effect on local communities - in addition to periodic German bombing or intruder fighters shooting up the airbases. British bombers crashing, exploding, catching fire, hitting buildings and endangering local people as well as servicmen were the reality of daily life in Yorkshire. Home crashes were numerous, a regular event for nearby communities - they accounted for about 15% of all losses of Bomber Command aircraft and aircrew, including nearly 3,000 RCAF airmen dying in crashes 'at home'.

A few of the home crashes of operational flights recollected by local civilians:

"Two Halifaxes collided in mid-air and spiralled into the ground near Selby. Among the 14 aircrew killed were a wing commander and a squadron leader... Five aircrew and three women civilians died when a twin-engined Wellington from East Moor crashed and demolished two houses in Huntington old village ...five more airmen were killed after their plane came down near Wetherby and the bombs on board exploded."

One man recalled this at East Moor:

"... a four-engined Halifax was taking off when it veered off the runway and came straight towards me... I started to run and when I looked back I saw the plane hit a tree. The rear gun turret and tailplane were sliced off... the rest of the bomber smashed into the guardroom, which became a ball of fire. I shall never forget the screams. Three men died in the aircraft and two in the guardroom... I watched the rescue services get the rear gunner out of his turret. He was still alive."

In 1990 Canadian servicemen returned to East Moor for a reunion and memorial dedicated to all who had served there. Later, one man was seen standing by the main runway; the local man who as a boy had witnessed the Halifax crashing approached this lone figure:

"I went across to him, and he asked if I remembered an aircraft crashing into the guardroom in 1945. I took him to the spot in my car. He started to cry. He told me he was the rear gunner. He had spent the last 40 years, including some time in a mental hospital, wondering how he got out alive."

There are similar stories relating to almost all the Bomber Command bases in Yorkshire, some remembered in detail, others simply in numbers, such as the 34 aircraft returning from bombing Berlin on 16/17 December 1943 which crashed trying find their base and land in low cloud; that was more than the number, 25, of bombers shot down over Berlin in that raid; we don't know the circumstances of that one night's home crashes, how many crew, civilians and houses were destroyed, just the number of aircraft, 34.

Training flights were also responsible for many home crashes, some which it's hard not to think were avoidable. Each bomber group had designated training bases; in 6 Group these were Topcliffe, Wombleton, Disforth and Dalton; nearby in 4 Group Marston Moor, Rufforth, Riccall and Acaster Malbis were training bases; they were termed 'heavy conversion units' - bringing together seven personnel to form the aircrew of a four-engined bomber which they would train to fly. The heavy bombers were difficult to fly, particularly on take-off and landing; flying and landing had to be practised with one or more of the engines 'feathered' to simulate what might happen operationally. Accidents were common, and some HCUs lost (meaning were killed or severely injured) around 25% of trainees before they graduated. Many of the trainees were in their late teens and saw their friends meet an early end in flying accidents before becoming operational. In Bomber Command as a whole 5,327 men were killed and 3,113 injured on training flights during the war years.

Instructors on training flights were usually experienced pilots who had survived to reach their 30-operation maximum. But it wasn't a safe semi-retirement duty for them, as the aircraft used were old, having been used on many operations, and sometimes under-maintained. One instructor explained:

"This was not so much the fault of the ground crew as the fact that all the Halifaxes had done several tours of ops and were really clapped out... it was necessary to start at one end of a long line of Halifaxes and do pre-flight checks to try to find one that was 'acceptable'. None were ever fully serviceable and anyone who wanted to fly by the book would never have flown at all".

Many of the training exercises were cross-country navigations, so reliant on accurate met. reports, as were operational flights, and reports of many operational and training crashes indicate that poor met. reports were contributory factors.

The Diaries and Crucible of War focus on bombing operations and their losses, not on home crashes and losses. But because training accidents occurred over home territory these have been recorded extensively by local people, both during the war and in the years afterwards, with memorials at some of the crash sites. For example, two Wellingtons on 2/3 Sepember 1942...

"...were on a night cross country exercise... due to bad weather they drifted off course. Instead of passing over Harrogate they drifted into the Pennines. It could have been that the aircraft was trying to pin-point its position on the dreadful night with heavy rain and strong winds as well as a very low cloud base... the Wellington hit Blake Hill... caught fire with ammunition exploding, there was only one survivor... The second aircraft Z8808 suffered a similar fate over the Yorkshire Dales... flew into high ground... they all survived."

Several training accidents from another specialist local publication:

"Bombers on daylight training flights from Riccall and Rufforth were involved in a mid-air collision over Copmanthorpe near York, in August 1943. Both crews were killed...

Eight civilians died, including three children, when a Halifax on a training flight in May, 1944, struck the spire of St James's Church, Selby, and fell on some nearby houses. The plane's crew of seven, five of whom were Australian, also perished...

The Heavy Conversion Unit at Riccall, near Selby, experienced 10 crashes in one month during September, 1943."

From many descriptions of training crashes, it seems training aircraft were fully loaded with ammunition (and bombs?) - presumably so the bomber would handle as it would operationally. If this is correct, one wonders why the same weight of non-explosive material wasn't loaded, to reduce casualties of any crash.

The port city of Hull was bombed several times. A local man has researched all the crashes of aircraft on Hull during the war - all of them were British or Allied aircraft on training flights, some causing widespread devastation, as shown below in the case of a RCAF pilot on navigation training in heavy thunderstorms and low cloud just one week after joining his squadron, 21 July 1945.

At Newark on Trent there is a cemetary containing the remains of "some fifty Polish airmen who died whilst being based at RAF Newton, they were simply in the process of learning to fly..."

Training accidents continued throughout the war years, and in some cases it appears that the competence of ground control was responsible. For example, on 15 January 1945, at Topcliffe, crew training in a Halifax undertook the basic exercise of repeated take-offs, flying circuits of the airfield and landing; in addition to the usual seven-man crew another pilot and flight engineer were on board. During the first run the aircraft swung to starboard, as four- engined bombers tended to; the pilot managed to correct this and the aircraft made the circuit and touched down. As power was applied for the second take-off the aircraft again swung to starboard but before it was corrected the starboard main wheel went off the runway; the port tyre burst and the aircraft ground-looped causing the port undercarriage to collapse. This was the pilot's first 20 minutes' solo flying at night in the Halifax; all nine aircrew were new to the Halifax. The crew were not medically examined and two hours later they were ordered to repeat the exercise in another Halifax; the starboard outer engine failed, and the inexperienced pilot failed to get the aircraft to climb to avoid rising ground around the airfield. The Halifax struck the ground in a snow-covered field near Felixkirk village, bounced across a lane and into woodland where it broke up; eight of the airmen died in the crash, and local people dragged clear the ninth man, seriously injured, but snow delayed getting him to hospital where he died on admission. Crash investigators concluded a major factor was the crew having not been medically examined to check they were fit to fly the second exercise that night.

The seven man crew were all RCAF; the two additional men on board were RAF Volunteer Reserve. This photograph shows six of the young men who died in this training crash.

Another publication noted that the:

"hills and valleys of the North Yorkshire moors made a sinister contribution to the coffers of the Third Reich. The traumas of crashes which happened at or so near to home bases ... affected the whole comminity... Fatalities were mounting in the communities everywhere yet even after the final victory... there will still casualties as crews continued training".

One such post-war training crash, and devastation of a Yorkshire village, was on 9 October 1945, when a Stirling bomber with its pilot on his last training exercise lost height and crashed into Tockwith. The village street, houses and gardens were littered with wreckage, 17 houses were damaged and many set alight by burning fuel; all the aircrew were killed and, miraculously, only one villager. "The village was in shock... as a small boy [I] walked down the street to see the devastation, houses flattened..." one local man recalled later. Short Stirlings had been withdrawn two years previously from bombing operations over Germany because of their inadequacies and consequent losses; they were about to be withdrawn from all RAF service, replaced by the Avro York - why on earth were lives being risked and lost training to fly one five months post-war? But it was not the last training crash: a 6 Group Lancaster from Leeming with a trainee crew crashed on 5 November 1945 near Ilkeley; four of the eight crew survived.

As well as the 10,360 fatal casualties (and 1,265 injured) on 6 Group's bombing operations against Germany, there were also 2,961 RCAF airmen killed in 'flying accidents' in Britain, 1,453 injured, plus 181 groundcrew killed with 216 injured.

Details of individual incidents come from local publications - see sources concluding Chapter 11 - by veterans and Yorkshire people some of whom lived through the war and experienced events first-hand, and from various commemorative associations. The latter seem to have ceased now, and the RCAF veterans have passed away. Their colleagues who died, in local crashes, as young men in the 1940s are buried at Stonefall Cemetary, Harrogate. It's worth saying again: the many thousands more who died over Germany are scattered God only knows where.

Chapter 8

Groundcrew

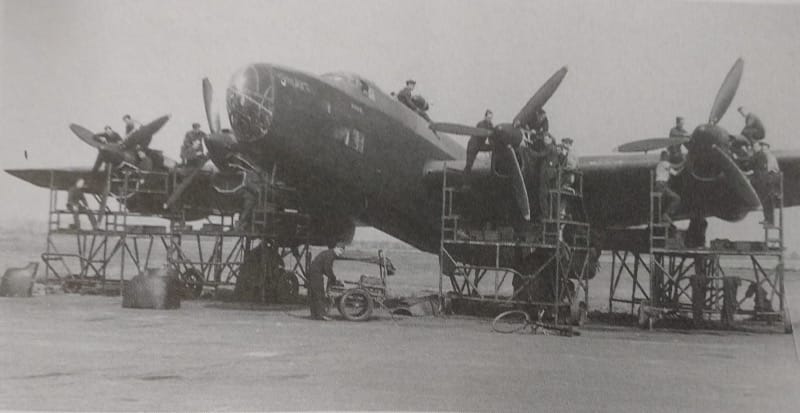

My father was groundcrew in the RCAF, one of the many men responsible for servicing and repairing, fuelling, arming and bomb-loading the aircraft that would take off often in very poor weather and darkness. Almost all of them were doing this difficult, vital work for the first time; few if any of the groundcrew were trained, experienced technicians, and four-engined bombers were just coming into service, new to everyone, then with a succession of new radio, radar, navigation and bomb-aiming devices to be added.

For groundcrew in Bomber Command there was nothing stable or settled upon which to confidently build experience and expertise, squadrons were shuffled between bases in the early years of the war, change-over from two to four-engined bombers was a major process, different types of four-engined bombers were quite different to service and repair, as were new improved versions of the same type, even the change from Merlin engines to the more powerful Hercules radial engine in a Halifax bomber required different knowledge and procedures. Like the aircrew, they were learning a vital, complex job whilst in the process of fighting a war. Some may have had more natural aptitude and skills than others, but that was about it.

Maintenance standards were a constant concern throughout the war; personnel were seldom given the thorough training and supervision needed, and seldom working under the guidance of older men who were experts in the many trades and skills involved or even experienced themselves; it was nothing like an apprenticeship. On occasions when a new base commander cracked down on maintenance, standards improved. 'Serviceability' of aircraft - getting them repaired and quickly ready to fly again - was vital to the bomber effort. Groundcrew worked often in the open air and in all weathers. Though not in as much danger as aircrew, it could still be dangerous work; in RCAF 6 Group, 181 groundcrew were killed and 216 injured during the war.

The work of groundcrew on a Bomber Command base was described thus:

"Many of the ground trades really worked hard and had a hell of a life on a bomber station. The fitters and riggers repaired aircraft and engines night and day in all kinds of weather. They worked out in the open or under a bit of canvas shelter. The armourers hauled and loaded bombs, changed bomb loads, fused and defused bombs, rain or shine, at all hours of the day... The fuel trucks... loaded the specified amount of fuel to get the plane to the target and back. There never was very much to spare... While all this was going on members of the ground crew who looked after an aircraft had to check it thoroughly. Engines would be run up and tested; radio men, radar men and instrument men would call at each aircraft and check various pieces of equipment and instruments. The camera would be checked and loaded wth film. Ammunition would be put in the turrets. The many thousands of rounds for the tail turret were carried in canisters near the bomb bay and ammo tracks... ran along the fuselage to the tail turret."

Aircrew who had experienced problems would then make test flights to check repairs or adjustments had been made, and return for more attention if needed. Aircrew would draw clothing, attend the pre-op briefing (target and route, met. officer's wind and weather forecasts, intelligence officer's briefing re enemy defences, radio, radar, navigation, decoy and bomb-aiming procedures...). Flying might then be delayed by a change in the weather at the base or forecast over the route or target, or cancelled altogether.

On some occasions late in the war, when Fighter Command could provide cover and enem

y defences were lower, squadrons conducted more than one operation in a day. In October 1944 Duisberg was attacked twice within 14 hours, with 6 Group involved; aircraft from the morning's operation got back to their bases at midday, and groundcrew "for the second time that day they had to load hundreds of thousands of gallons of fuel, oil and coolant, several million litres of oxygen, and millions of rounds of ammunition" and check and repair the many electronic, radar and radio aids for navigation, bomb-aiming and jamming or evading the enemy's detection and defensive measures, for that night's second attack on Duisberg. One small part of the two operations was to "destroy steel works", and all the rest (of 2,013 sorties) was intended to "destroy dispersed intact areas... aiming the bombs at any built-up area, no matter what it was" - as described by a gunner from 429 Squadron.

One incident at Tholthorpe indicates the dangers not just in the air over Germany but also at home, on the base, and the teamwork of all involved. On the night of 27/28 June 1944, all aircraft of 425 Alouette Squadron had returned safely from a raid except one which approached on three engines; on landing it veered into a parked Halifax which was full of fuel and explosive. Both aircraft burst into flames; the base commander Dwight Ross and one of the groundcrew, Corporal Marquet, managed to pull the pilot, Sergeant Lavoie, out of the wreckage. Then the 500-pound bombs in the parked Halifax exploded, further engulfing the planes; the rear gunner, Sergeant Rochon, was trapped in the raging fire - Ross, Marquet and bomb aimer Joseph St Germain were hacking away the turret to free him when another bomb exploded, then petrol was seen pouring towards nearby parked aircraft which other groundcrew rushed to move away. St Germain was removed from the rear turret in time. All were seriously injured; Commodore Ross had severe injuries requiring amputation of one arm.

It would be easy to think of groundcrew and what they did as less important than the aircrew but they were complementary and essential to each other. Aircrew certainly seem to have recognised that. A poem penned in appreciation by RCAF aircrew described The Fitters Lot:

"Lashed by gales sweeping the bomber field

Perched atop ladders gripping cold steel

The erks labour on - so much to do

Grease stained battledress, field service caps askew

Chapped lips and sore, windblasted cheeks

Noses, petrified, dripping red beaks

Cold fingers dropping the oil slick tools

Ice on the hardstand formed into pools

Grimy fingers protrude through holed woollen gloves

Reach for the cowling covers, and the bolts above

Stripped threads, blood and scuffed knuckles abound

Hungry and tired - these men on the ground

Red tarnished brass, bloodshot eyes, frozen feet

Yesterday the wold was lashed by North Sea sleet

So many u/s aircraft after each flight

So many are needed for the raid tonight."

Aircrew and groundcrew, they were all young men doing something they'd never done before, and under extreme pressure. When an aircraft failed to return, for the groundcrew that was 'their' plane lost and their colleagues killed. When an aircraft turned back early due to some fault in its equipment, there were questions of - was it poor maintenance, or inherently unreliable equipment (as with some new navigational and radar aids) - or an aircrew-morale problem? (the latter is discussed in more detail in Chapter 11).

One of the groundcrew at Linton, an engine fitter, recalled witnessing the trauma of aircrew on the base. One of the bombers he had serviced taxied ready for take-off, then stopped:

"I went out to see what the trouble was. I found the pilot slumped over the controls sobbing and crying. The crew just looked vacant. They had had enough... It was a grim time for us all... "

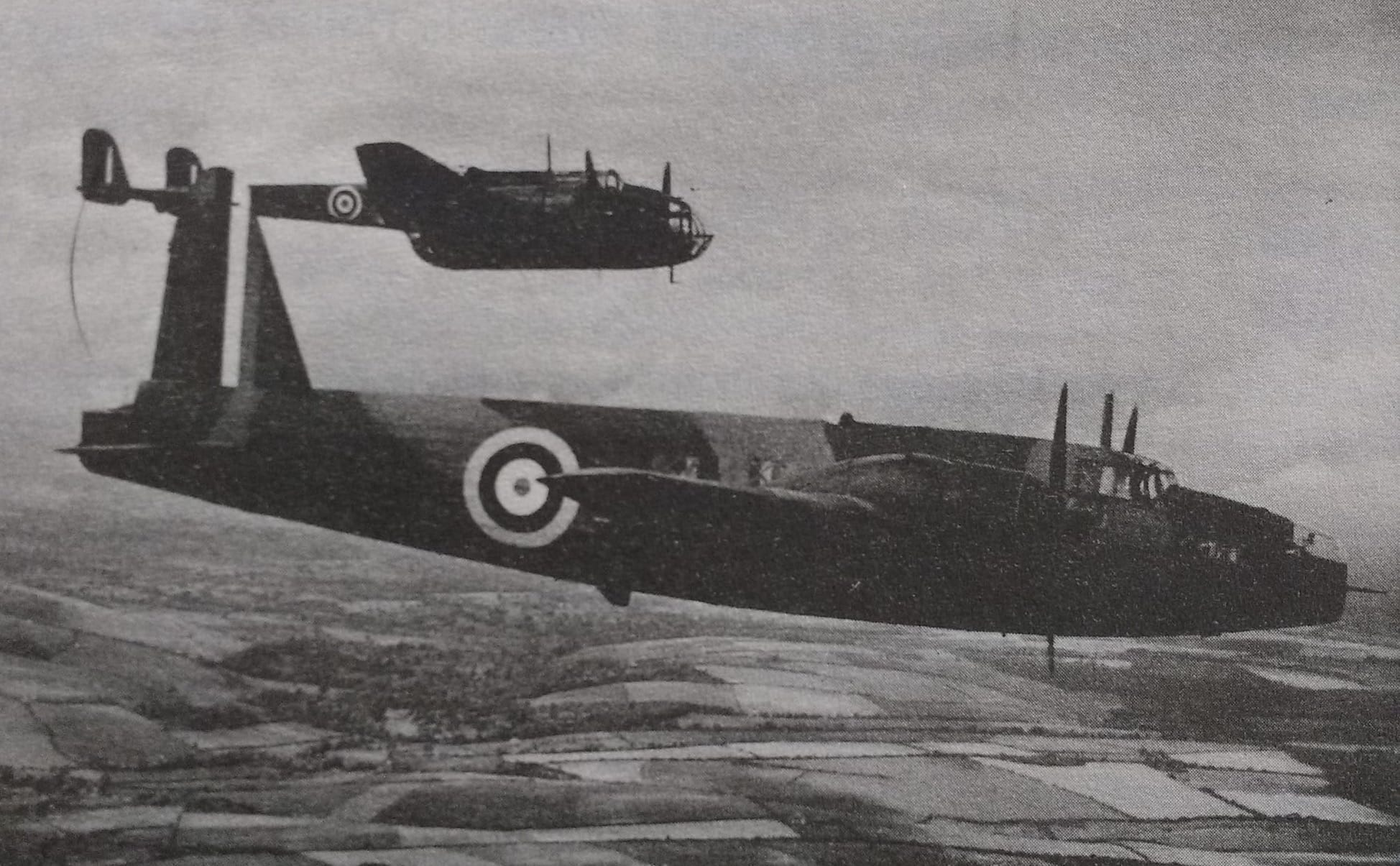

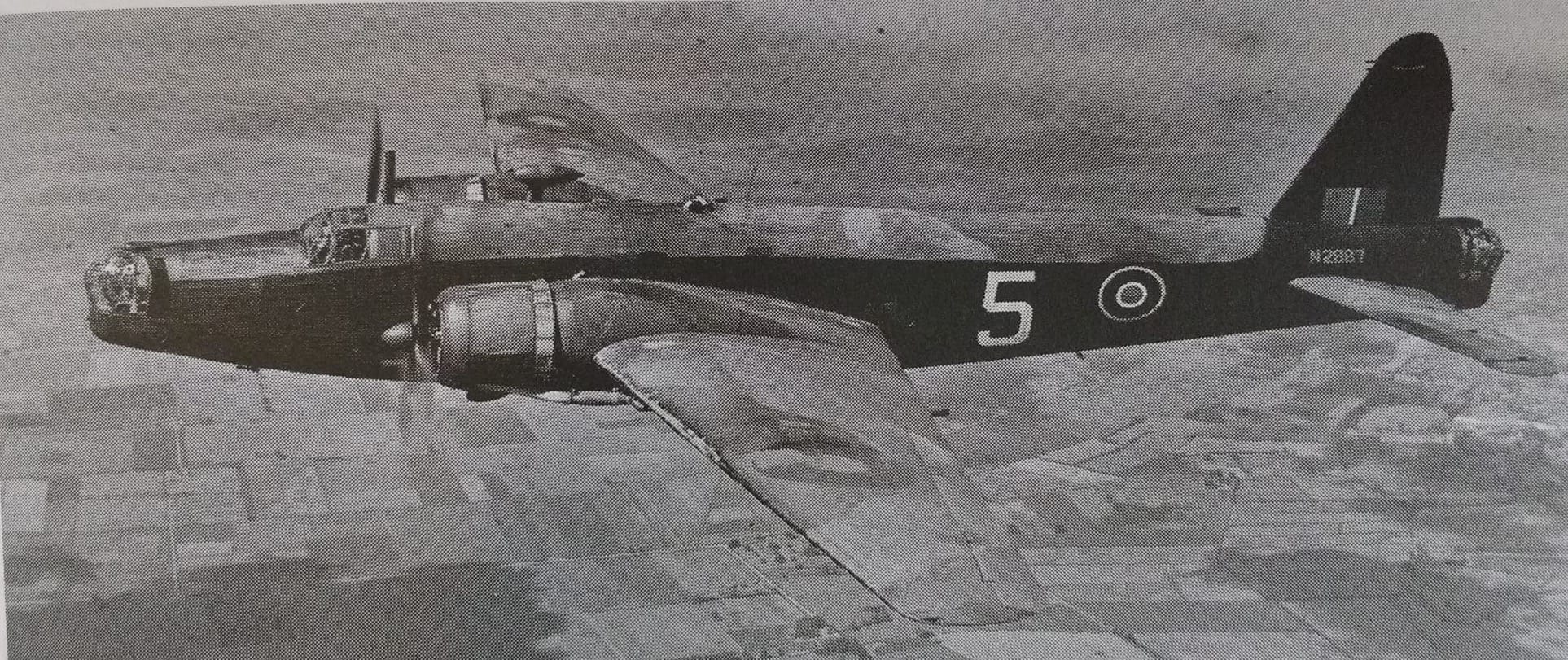

Vickers Wellingtons were in service before the outbreak of war, as were Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys and Handley Page Hampdens, and were the mainstays of Bomber Command during the early years of the war. The first Wellingtons were unreliable and they went through many updates; there were also adaptations for roles such as Coastal Command. Wellingtons were in service throughout the war, unlike Whitleys and Hampdens.

Four-engined heavy bombers, with greater bomb-load, longer range, higher altitude, started in development in the late 1930s. The first, the Short Stirling, proved unsatisfactory, in its limited bombload and altitude capability; it was particularly difficult to handle on take-off and landing. The Handley-Page Halifax went into service in late 1940, with several updates produced to correct deficiencies; there was dissatisfaction with the Halifax II despite which it was produced and used in large numbers. It came into service in 1942

; similarly the Halifax V was regarded as deficient. The Halifax III was the best of these variants, and flown in 420 and 425 squadrons. The Avro Lancaster, with superior bombload, altitude and flying characteristics, came into service in 1942 but initially was available in smaller numbers than the Halifax; an improved version of it was produced in larger numbers; 425 Squadron was transferring to Lancasters at the time the war in Europe ended in May 1945.

The heavy bombers were put into service as soon as they were available, such was the operational need for them. Crews were flying untested, unproven aircraft of a size, power and carrying capacity previously unknown.

The Allies were reliant on British heavy bombers because they could carry larger bombs (up to 8,000-pounds, later increased to 12,000-pounds - approx 6 tons or 5,500 kg) and bigger overall bombloads than American bombers.

Harris complained frequently about the slow production and delivery of new bombers, and then quickly about the limitations or inadequacies of each type. It is unclear what was the process by which the specification for each new type was decided; were the aircrew flying bombers and groundcrew trying to keep them seviceable consulted? Such questions arise, but the Diaries and Crucible of War provide little such information. This is an interesting area for investigation; for example, Air Ministry specifications limited heavy bomber wingspans to 30 metres which may have affected the take-off and landing stability of heavy bombers, especially the Stirling; the Lancaster, a 'better' aircraft, exceeded that wingspan; but aircrews did not prefer the Lancaster in one respect at least - it had much smaller escape hatches than the Halifax it replaced, an important consideration for aircrew in bulky clothing having to hastily exit a 'downed' bomber. Nor is much reported on how production priorities were decided between types of bomber (why were the inferior Halifax IIs and Vs produced in such numbers?), or between bombers, fighters and all the other war material needed.

Of all the aircraft produced, only the Spitfire and Mosquito stand out as being 'ahead of the game' when introduced; other aircraft such as the Wellington, Halifax and Lancaster were improved upon version by version (with some new versions seemingly not being improvements at all). One reference in the Diaries notes a staff officer complaining that the Americans could:

"develop, produce, and operate more progressive defence armament in six months than we can do in two years".

No satisfactory downward-viewing rear turret (to counter attacks from behind and below) was produced, likewise a 'belly gun' for the Halifax, likewise changing from the 0.303 calibre of gunnery in British bombers to 0.5-inch (German JU88 night-fighters had armour which the lighter guage could not penetrate, as well having as the heavier calibre guns with which to attack British aircraft). Only in 1944 did work start on the Lancaster IV equipped with six 0.5 inch guns, but it seems that until then Bomber Command had given little thought to defending its bombers; fighter escorts were not used until later in 1944, after the Operation Overlord Allied landings in Normandy when bombers were making the shorter daylight runs in support of ground troops. Until then, British bombers were pretty much sitting ducks for German night-fighters and flak, high loss rates apparently accepted and compensated for by simply putting many more aircraft into the sky. However, every heavy bomber lost was seven crew lost as well.

To read of the repeated re-organisations and transfers of personnel especially early in the war, and the inadequacies of long-awaited new bombers, and inferior armour and defensive firepower of British bombers, their vulnerabilities which were never removed, and constantly changing tactics, and the navigational and targeting errors (even late in the war, only 20% of bombs on night operations fell within three miles of the target, in the best of conditions) - to read of this and more, as in Chapters 9 and 10, is shocking. But that reaction overlooks the fact that night bombing had never been carried out on this scale before; they were learning 'on the job' how to do it, and with few exceptions they were young men with little training or even work-experience, not battle-hardened, and not practiced professionals in what they were risking their lives attempting.

In reading detailed accounts of Bomber Command's operations, where critical reactions do remain for me is regarding senior officers' poor planning, anticipation and lack of adaptability; at worst, examples of 'that didn't work, let's do it again and hope for a different outcome'. Each time, it was more aircrew lives lost. Not all those lives need have been lost to achieve the intended result, and in fact the intended result was not achieved, as the next two chapters describe.

Chapter 9

The Bombing

Before 1943 the results of British night bombing efforts had been poor, hampered by inadequate aircraft, poor navigation and bomb aiming skills and equipment, confused by a strategy calling for precision targeting of German military facilities but which defaulted in practice, through inefficiency, to random 'area bombing' mainly of cities.

Reports from the Air Ministry and other senior sources at the time referred to casual attitudes and lack of skill among aircrew and groundcrew, but it is difficult to understand why the importance of navigation and bomb-aiming were not appreciated at an early stage by the Air Ministry and at senior RAF levels, and better training and equipment not devised from the start. In 1940 the Luftwaffe was able to cause substantial damage to Coventry, London, industrial centres and port cities, but three years later many RAF and RCAF bombing raids on Germany still failed to even find their targets, or bombed without accuracy, and suffered significant losses of aircraft and crew.

During 1943 Bomber Command dispensed with the second pilot (causing some alarm; this must have increased stress on pilots flying eight or nine hour missions in darkness and bad weather); this was done to allow more specialisation in the roles of navigation, wireless/radar operator and bomb-aiming. Mistakes still occurred, so it was decided that the final run to the target must be a timed approach on a set speed and course from a fixed reference point. Less happened in practice than had been decreed in theory; despite navigation aids, much depended on pre-flight meteorological predictions of wind speeds (at various altitudes) and the navigator's assessment of actual wind speed in flight, at which it seems very few were proficient.

Gradually, results did improve somewhat and losses were reduced, as many radar and radio advances were made by Bomber Command in the effort to improve navigation and bomb-aiming, better training was given in these areas, better aircraft came into service and tactics were adopted of 'concentration' (massing hundreds of bombers into one 'stream' so that German defences might be overwhelmed and areas swamped with explosive without precision needed), or multiple bomber streams, or shorter bomber streams stacked vertically to reduce

the danger-time over the target, or diversion raids on other targets far apart. New tactics such as Pathfinder advance sorties to mark targets were also developed.

Likewise in Germany there were new developments to counter Bomber Command operations. Flak, searchlights, radar innovations and night-fighters were controlled from ground stations in a very thorough, systematic operation requiring many personnel; night-fighters were tightly controlled, allocated one bomber to target, and restricted to a 'box' (defined area). Germany stuck rigidly to this effective system, even when Bomber Command's new tactics and improving equipment started to achieve some highly destructive raids, such as against Essen and Hamburg (the 27/28 July bombing was termed Die Katatstrophie).

National characteristics were in play: in Germany the rigidly controlled