Survivors, Early Deaths & Mysteries

Orphaned at 7, a widow at 29, 6 children. Born in 19th century poverty, she moved from Glasgow to London as a young girl, fell in love and made a life there, fled a drunken second husband back to Scotland. Christina was a survivor, deserves to be remembered, and the times she lived in.

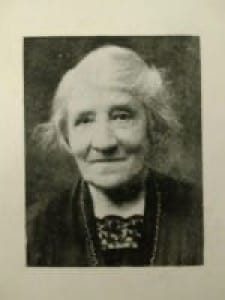

Untold stories of forgotten people who lived interesting lives, survived hardships in different times, long lives or lives cut short. A mother and a beloved husband who died too young, a bad father who lived too long, two sisters who were survivors. One was my great grandmother Christina, living from the mid 1800s until the 1950s. She died when I was 11, I could have met her, but no-one mentioned her.

Chapter 1

Christina Potter

Christina had a long life, orphaned at age seven, a widow at 29, six children. Born in 19th century poverty, she travelled from Glasgow to London as a young girl, fell in love and made a life there, had children, was widowed, fled from a drunken second husband back to Scotland. She was a survivor, my great grandmother; she deserves to be remembered, and the times she lived in and survived.

Christina was born in 1863 in Glasgow, the youngest of four children in a working class family. Her parents were Edward and Christina Potter who had married in Eccles in Lancashire in 1850. Edward was a watchmaker, then unemployed, then a street hawker selling anything he could on the streets, then a dealer, salesman, boiler maker, engine maker - any manual job he could find as the family moved around the industrial towns of Lancashire and the Midlands, always seeking work and taking cheap rented accommodation.

There were 'lodging houses' in Manchester and other industrial towns, providing the most basic shelter (one room per family, no sanitation or clean water) at a few pennies per day for the many near-destitute people swelling the urban population far beyond the number of houses available (or affordable). During the 1800s cities attracted people from the countryside where many farmers were tenants unable to provide a living for their children. Disease was rife in the overcrowded and unsanitary cities, living conditions were awful. This was part of Britain's industrial revolution and empire-building; people were its fuel, it chewed them up and spat them out.

Lancashire and the Midlands were suffering economically from the sudden closure of cotton-spinning mills in the early 1860s, when civil war in the United States stopped the supply of raw cotton from the southern states. Lancashire and Manchester had developed major textile industries and become reliant on them; cotton workers were the highest paid of the working class, and their sudden mass unemployment had severe effects on the wider community.

Edward and Christina had three children there, Ann Marie born in Salford in 1851, Edward Robert Simpson Potter born in Chorlton in 1853 and George Thomas Potter born in Manchester in 1856. In 1861 they were living in Everton. The first son was named after his father and also given his mother's maiden name Simpson; Christina Simpson was born about 1825, the daughter of Joseph Simpson and Harriet Tipler. The name Christina is important - this forename was passed down through five generations to the present day.

In the early 1860s the Potter family travelled to Glasgow, perhaps by coach but there were trains from London via Manchester to Glasgow by then. The early trains generally charged 1 penny per mile, half-price for children, so the journey cost them about £8 (equivalent of over £1,000 today); this fare was set as being similar to the cheapest horse-drawn coaches but with the advantage of trains being faster. To spend this much, things must have seemed pretty hopeless for them in Lancashire, but somehow, Edward often out of work, children to feed, they scraped together the fares.

The attraction of Glasgow was that it was expanding and flourishing, with more work opportunities than recession-struck Lancashire offered. That may be how it looked to Edward from afar, but Glasgow had an overpopulation and housing crisis even worse than the Lancashire towns. Not only had Glasgow attracted working families, it had become home to thousands of destitute people fleeing Ireland's recurrent famines and impoverished Scots from the Highland Clearances (clearance of crofters by landlords preferring more profitable sheep farming). Many properties had become lodging houses, more houses were built on gardens for the same purpose; central Glasgow around the river Clyde was a warren of dark, narrow passage ways. Floor space in the lodging houses was crowded with beds, palletts, straw to cram in as many paying bodies as possible; a 'midden' outside was the only sanitation, and there was no clean drinking water until late in the 1800s. In these conditions, disease proliferated; typhus, cholera, smallpox were endemic in Glasgow, with severe outbreaks every few years. Many contemporaneous reports lamented the living conditions in Glasgow, and new hospitals were built towards the end of the century but improvement in housing was slower.

When German philosopher Friedrich Engels visited the slums of Glasgow in 1844, he said, "I did not believe... that so large an amount of filth, crime, misery and disease existed in one spot in any civilized country."

In one inner city area, the Gorbals, many of the previous small terraced houses had been torn down in the 1840s to build five and six storey tenements capable of housing many more people. But this did not improve living conditions; the Gorbals became synonomous with squalor, lack of hygiene and overcrowding. Close to the Gorbals and either side of the Cyde were 'unimproved' and similarly crowded districts full of lodging houses where the Potter family came to live and their fourth child, Christina, my great grandmother, was born, at 69 Carrick Street, on 6 January 1863. A few years later they moved to 11 Main Street in the Gorbals.

The first early death in this true story was of young Christina's mother, who contracted typhus and died, aged 45, on 10 February 1870 in the Fever Hospital. There had been a severe typhus epidemic in the winter of 1864-5 leading to the opening of the Parliamentary Road Fever Hospital; the next typhus outbreak in Glasgow started in 1869. Typhus occurs mainly in overcrowded, unsanitary living conditions and with under-nourishment; it develops rapidly, with fever, chills, prostration, nausea, and in some cases coma and delirium; pneumonia, kidney failure and cardiac failure can result. Typhus is passed person to person; rapidly moving Christina's mother to the Fever Hospital may have saved the children from getting typhus, as well as sparing them living in the same room with their mother's illness and delirium.

Losing your mother is bad enough, but what made this worse for Christina (aged 7), Edward and Robert was that their elder sister Ann Marie had married the previous year and moved out. And their father Edward Potter had abandoned the family, moving back to Lancashire. So upset (or ashamed?) were they all by this, that when Ann Marie notified the registrar of births, marriages and deaths she declared their mother was the "widow of Edward Potter, engine fitter". In fact, he was not dead, but alive, elsewhere.

So after moving home many times during their childhood, Christina, Edward and Robert had to leave the latest family home and become lodgers with another Glasgow family. The 1871 census shows them living at 92 Wellington Lane, in the McInnes household: Christina aged 8, Robert 17 and George 15; Robert had dropped his father's first name and was working as a founder, George was working as a brassfounder, their wages paying the rent and leaving precious little for essentials. By this time, April 1871, Ann Marie and her husband had left Glasgow and moved to London.

Moving out of the McInnes lodgings, Robert Potter got married five years later, to Annie Millar (they named their daughter, born 1880, Christina - there seems to be a lot of fond remembering of their dead mother). Brother George lived with the couple, still in Glasgow. On his 1876 marriage certificate Robert stated his father Edward to be deceased, as had Ann Marie previously. Christina, by then 13 or 14, soon followed her older sister Ann Marie to London; by 1881 at age 18 she had a live-in job as a general servant at 52 Isledon Road, Islington, in the Tooley household which ran a small dairy business. By this time Ann Marie and husband and young children had moved back to Scotland, continuing the family pattern of moving about to find work - or of un-rootedness, nowhere that is really 'home'.

So Christina was a young woman on her own in London. The city was growing in population and expanding outwards in the mid-1800s; this continued, with new terraced housing densely packed on what had recently been fields. Areas of formerly middle-class housing were becoming what we call today 'houses of multiple occupation' for working class families on short-term rentals, who moved often if they were in and out of work or rents increased. Christina was fortunate and/or smart to find a job which gave her more secure accommodation than might have been the case, and in a dairy which with its surrounding customers was likely to remain in business. It would have provided her with a small room, possibly shared, some meals and a very little cash in hand.

Raymond James lived at 13 Monsell Road, which was close to Isledon Road. Raymond was working as a ‘carman', driving a horse and cart for a living. Christina and Raymond may have met on the nearby streets, or perhaps he was delivering to the Tooley dairy, but they did meet and fell in love. They married on 3 August 1884 at Islington parish church; he was 29, she was 22 and still at the Isledon Road dairy. On the marriage register Christina gave her father's name as Robert, not Edward; it may be that she misremembered her older brother Robert as her father, or did not want to remember the abandoning father Edward (although that name is passed down the generations). Both Christina and Raymond signed the marriage register, indicating they were literate; their generation was the first to have mandatory primary-age schooling (introduced in several statutes from the 1860s) - previous generations often signed their name with an X, as did Edward on Christina's 1963 birth certificate.

Three years later their first child, Mary Christina James, was born, on 23 June 1887; they were living at 43 Chalfont Road, off St James' Road in the Holloway area, but the child was born at the City of London Lying In Hospital in the Holborn area. Does this suggest it was a difficult birth? And three years seems a long time for a first child to be born, so Christina may have had miscarriages previously.

Florence Maggie James was the second child, in 1889, born at 122 Georges Road, Holloway. Their first son, Raymond, was born in 1890, at 57 Eden Grove, Islington. All these addresses are close, within walking distance.

Six years later the family were living in better, more modern accommodation, at 281 Farringdon Buildings, Farringdon Road. This was one of several model dwellings schemes in the late 1800s aimed at providing better housing for the 'working poor'; the street numbers were 68-86, so no. 281 may refer to a flat in one of these multi-storey buildings, which were demolished in the 1970s.

But Raymond James was another early death in Christina's young life. He died, age 35, on 25 September 1892 at St Bartholomews Hospital, of “pneumonia and delirium tremens”, and the 'informant' of his death was not Christina but the hospital superintendant. Driving a horse and cart in all weathers, on the filthy and coal-smoke-filled streets of London could well lead to pneumonia. Suffering from this and delirium tremens sound like a slow and painful death, awful for his wife and three small children to witness, to the extent that he could not die at home. Reminiscent for Christina of her mother's painful death when she was a child.

Christina may not have known she was pregnant when Raymond died. On 4 May 1893 May Frances James was born, at 73 Eden Grove, Islington; on her birth certificate her father was stated to be "Raymond James (deceased)." In the few weeks before he died, ill and delirious, could he have become her father? A mystery.

Christina's story continues - she lived for over 60 more years - in Chapter 3 as Christina James, her dead husband's surname by which she was known for the rest of her long life, except for two occasions, as were her six children (some by other fathers). She also remembered him by naming her first son Raymond, and this name also carries on down the generations.

Another mystery is Ann Marie's husband Daniel Connal. That was his first name when they married in 1859 and in the 1871 census, but on the baptism records of two of their sons in 1875 he is named as Donald Connell. The baptism mis-spelling of Connal is understandable, but he continued to be known as Donald (Donald B. Connal in 1901 census, though he had given his name as Daniel in 1881 census) and he died as Donald Brookes Connal in 1918, with Ann Marie still alive.

Like her younger sister Christina, Ann Marie was another survivor, also living a long life, moving between Glasgow and London and back; she had nine children and out-lived her husband. When she married Daniel Connal she was 18, her occupation described as a book folder. They gave the marriage registrar the same address, 54 Commerce St, Tradeston, Glasgow, so they had probably set up home together first, but they did things properly - the marriage certificate states it was a ‘regular’ marriage with the banns (public declarations for three weeks of the intention to marry) being called “according to Church of Scotland". In Scotland at the time there was another form of marriage, 'by declaration', whereby a couple could declare themselves married in front of two witnesses (anywhere, usually in a private house) and from this get a sheriff's warrant to obtain a marriage certificate, on which their marriage was stated to be 'irregular'; this was to save a couple, possibly needing to get married in a hurry, from living 'in sin' and to legitimise children.

Perhaps influenced by her father's frequent joblessness, she married a man already established in a skilled trade - Daniel, age 25, was a compositor journeyman, later a printer. Both his parents had died, and witnesses at the wedding were Peter Wilson and Janet Wilson, siblings of Daniel’s mother, so his uncle and aunt, which indicates the family's approval of the marriage.

They had moved to 21 Balmanno St, another slum area of Glasgow (since redeveloped) by February 1870 when Ann Marie's mother died. With Ann Marie's two brothers and sister Christina parentless (Edward had disappeared) and suddenly homeless, they were put into lodgings. In late 1870 Ann Marie and Daniel had a child, John Edward Connal, and soon after they moved to London, living at 22 Waxwell Terrace, Lambeth. By 1875 they had two more children, Donald Wallace Connell and Robert Simpson Connell, and were at 56 Gloucester Street, in the Bloomsbury area of London. Two other children were born, George Thomas (circa 1877) and Maggie May (circa 1879), before they moved back to Glasgow with four of their five children, to 35 Raglan Street; their first-born, John Edward, either stayed in London or lived separately back in Scotland (but, at age 11?) or had died. A sixth child, James Edward, was born in Glasgow in 1880. Again, so many of the same names being repeated in later generations, a kind of kinship and family remembering.

In 1901 they were living at 22 Garscadden Street in Glasgow, with three more children, Christina H. S. Connal (circa 1884), Agnes M. Connal (circa 1887) and Mary T. Connal (circa 1894). Ann Marie lived on after her husband's death in 1918, dying aged 84 on 23 April 1935 at 48 Dumbarton Rd, Clydebank, the informant of her death being Robert F. Angus, son in law; at death she was named Mary Ann Connal, but her age, mother and father named on the death certificate confirm this was Ann Marie Connal.

Edward Potter was a survivor too, of a sort. After leaving his wife and children, he next appeared in Liverpool in 1871, in the Royal Infirmary, listed as a 44 years old widower and boiler maker. By April 1881 he was in the Brownlow Hill Workhouse, Liverpool, described as married (not widowed), a boilermaker born in Manchester. In the next census, 1891, he was living at 18 Truman St, Liverpool, with the widow Isabella Jones, stated to be a housekeeper. They married the following year; his father was described on the marriage certificate as Robert Potter, a smith. Edward died on 2 November 1895, age 68, back in Brownlow Hill Workhouse.

We'll never know how Christina met Raymond, the love of her life, seemingly, who she lost after a few years but kept his name for the rest of her long life and gave to her children born later to other fathers. For children, how their two parents met and fell in love can be the most heart-warming of family stories, regardless of how that relationship turned out later. But the 'how we met' story has to be told, and often isn't. I catch a glimpse of the start of such a story in this photograph of a Victorian girl and boy, younger than Christina and Raymond were, an unknown pair, just possibly the spark at the start of another long family line.

See also Wikitree (free, dates & biography), MyHeritage (subscription, dates)

Christina Potter was my great grandmother on the maternal side of the family. There is no photograph of the young Christina, probably none taken. The first image in this chapter is of an unknown Victorian girl.

Chapter 2

Raymond James

Raymond's was one of the early deaths in these stories. He and his origins are also a mystery, in several respects.

When Raymond's birth in 1854 was registered, his mother X'd the register rather than signing it, and gave her address as 32 Tavistock Square, London; but she gave birth to him at "Race Hill, Launceston" in Cornwall. The Tavistock Square address is a grand, 5-storey house overlooking one of London's much-prized gardens, created in 1806 and open to the public but seen mainly as a privilege of monied owners of the fine Georgian houses facing it.

No father is listed on Raymond's birth certificate, so he was given his mother Sarah James' surname. His birth on 28 December 1854 was not registered in Launceston until 7 February 1855, close to the maximum delay of 42 days for registering a birth; does this suggest a long recovery from giving birth, or could she have given birth in London and travelled home to Cornwall to register it?

At 32 Tavistock Square Sarah was likely a servant; when her pregnancy became known she would not have been allowed to remain, so was made homeless in London in mid-1854. St Pancras Workhouse, which is close to Tavistock Square, admitted an 18 year old Sarah James on 5 August of that year, her (former) occupation listed as "service". Two days later she was discharged, said to be at her own request; if the workhouse guardians learned she was from Cornwall, they may have paid for the journey back there to avoid her and her child becoming an ongoing burden on local taxpayers.

Raymond and his mother Sarah returned to London some time after February 1855 and well before 15 March 1860 when Sarah gave birth to William, again with no father listed on the birth records. She returned well before that date, because the 1861 census records Sarah having had another child, Anne, before William. Information on censuses can be inaccurate, because it is given verbally by the occupants of the house when the census enumerator happens to knock on the door, and no documentary checks are made at the time or after. But several later censuses give consistent information regarding these two of Sarah James' children.

The 1861 census lists Sarah as aged 27 (indicating born circa 1834), with two children Anne James 2, William James 1, both born in London, and a cousin Susan Smith, 14, a general servant, born in Launceston. There is no mention of Raymond, who would have been age 6, so surely not working on a live-in basis anywhere else. Mystery.

William was born at 27 Goldington Street, Pancras Road, in 1860, and that was the same address in the 1861 census. Sarah was noted as head of the family, but the property was also occupied by seven members of the Harrow family; it was (and is) a 3-storey, 2-bay terraced house, so not a small, low-rent type of house. Sarah was described as an 'annuitant'; who or why she was being paid an annuity or on what conditions is unknown, but it explains how she could live with her children in London without the earnings of a husband or other relative, in a decent middle-class type of house.

Raymond does not appear in the 1861 or 1871 censuses at this or any other address, for which I can find no explanation. In 1881 he was recorded as a carman and single, age 26, born circa 1855 in Launceston, Cornwall, living at 4 Scholefield Road, Islington, as a lodger, with his sister Annie (not Anne) James 22, brother William James 21 and sister Sarah James 17, all three of them born in St Pancras (these sibling relationships are identified on the census). William was also working as a carman, Sarah was a dyer and Annie was described as an ironer. It seems Raymond was looking after his younger siblings, and lodging them in what was a good quality newly built house near Archway, shared with or sublet from the Brooks family (4 persons). This was further north from the inner St Pancras area where his mother and siblings had lived previously. Around the Archway area new streets and housing were being developed at that time, and 4 Scholefield Rd exists today.

It would have been easy for Raymond to get work as a carman or carter, driving one of the many types of passenger carriage or a goods-carrying cart; there was much demand, and these were the only modes of transport, apart from walking, for many years. People routinely walked much longer distances, functionally, not just for recreation as nowadays.

But London was a horse-drawn society in the 1800s, pre-combustion engine, and remained so even as railways developed more inner city stations. Horses were functional tools of a trade, seldom (and then only in rich households) regarded creatures of beauty and pleasure, sentiment, as today. Veterinary care seems to have been minimal.

From 1830 the horse-drawn omnibus met the need for large numbers of people to cross London to and from work, where previously they had had to rely to much smaller hackney carriages; omnibuses met the need to commute, and increased it - by 1850 there were 1,300 omnibuses. Ambulances, fire engines, dust carts were horse-drawn.

Businesses large and small needed transportation on a regular basis; goods and materials had to be collected from and delivered to the London docks, factories, railway stations, nearby towns and farms. Many businesses would own the horses and carts they used (Raymond was recorded as a "corn merchants' carman" on one document). Drivers might start by hiring a horse and cart, and building up a casual trade with local shopkeepers etc, freelancing, as Raymond and William may have done. 'Owner-operator' cart and coach drivers had nowhere to keep the their horse and cart overnight in the crowded streets and dense, mostly terraced housing, so there were ‘Livery & Bait’ businesses to store the cart and stable and feed the horse. All these arrangements were negotiable, with ever-present competition from other drivers; earnings for drivers were probably low and variable, encouraging them to work long hours in all weathers as, it may be, Raymond did, contracting pneumonia in his 30s.

With so many horses on the streets - an estimated 300,000 in London - there were problems other than congestion. Health and pollution problems: streets became covered in dung (10kg per day per horse estimated) which produced a foul and slippery slurry in wet weather and a dusty mat in summer; wet or dry, this was scattered by passing vehicles across houses, shopfronts and pedestrians; the dung attracted clouds of flies, both unpleasant and spreading disease. Crossing-sweepers made a living clearing paths for people to cross streets. As the population grew, and London grew, so did the number of horses and carts, roads becoming gridlocked and the clatter of horses and carriage wheels became so deafening that straw was laid outside homes and hospitals to muffle the noise. It become so bad that it was called ‘Great Horse Manure Crisis of 1894’ and The Times predicted “In 50 years, every street in London will be buried under nine feet of manure.”

Electric hackneys and trams were introduced towards the end of the 19th century, but horsepower continued to be in everyday use, as this 1905 photograph shows.

There seem to be no birth or baptism records for Annie and Sarah; there is a birth certificate for Wiliam but no baptism record. It is possible that the girls' births were registered under another surname (a father's?) but their mother chose to call them by her surname when answering census questions (however, William's birth, between the births of the two girls, was recorded as James). Where their mother Sarah was in 1881 is unknown, or when/if she died. No workhouse or similar instutional records have been found for her or them. The only later reference to her is in Raymond's 1884 marriage certificate, where he does not state either his mother or father were deceased, and he states his father was "Raymond James, mariner"; this may be a fiction to hide illegitimacy, there is no such marriage record, and an unmarried Sarah James liaising with a Raymond James seems unlikely for the concidence of surnames; also, if this man was the father of the Sarah's two daughters as well as her sons they would have the James surname and birth records could be found.

But someone was paying Sarah James an annuity, for some reason, and she was either conceiving children with this person, or others. The annuity allowed her to live with her children in a fairly decent house, albet shared with another family. The sense of deliberate obscurity and absence of normal records such as birth certificates for Annie and Sarah (daughter), suggests to me that the always-unidentified man was a member of one of the posh houses the mother Sarah had worked in as a young woman. That Raymond, the oldest child, seems to have distanced himself from his mother at a young age could also suggest there was something untoward going on. But, those are guesses, it's another mystery.

Between April 1881 and August 1884 Raymond had moved to 13 Monsell Rd, Islington - he gave that as his address when marrying Christina Potter on 3 August at Islington parish church. Their marriage certificate names him as Raymond Jones; that, combined with Christina naming her father as Robert Potter instead of Edward Potter made this look like a misidentification. But no other marriage record was found. And the actual marriage register - which the two parties sign - showed him signing as Raymond James; it is clear from the different handwriting on the register that a clerk misread his signature as Jones when completing the register and writing the certificate. His other details - age 29, bachelor, carman - are consistent with other records.

By June 1887 Raymond and Christina were living at 43 Chalfont Road, off St James' Road, Holloway, when their first child, Mary Christina James, was born. Two years later they were at 122 Georges Road, Holloway, when Florence Maggie James was born and at 57 Eden Grove, Islington, in 1890 when their first son, Raymond, was born. That is their address in the April 1891 census too, where the children are named as Christina James (omitting 'Mary', as she did later in life) aged 6, Florence M. James 1, and Raymond J. James, 9 months, with a cousin James Underwood 18. The Underwood family connection is a mystery; there was also a Thomas Underwood, age 14, living at the Tooley dairy in 1871 at the same time as Christina pre-marriage.

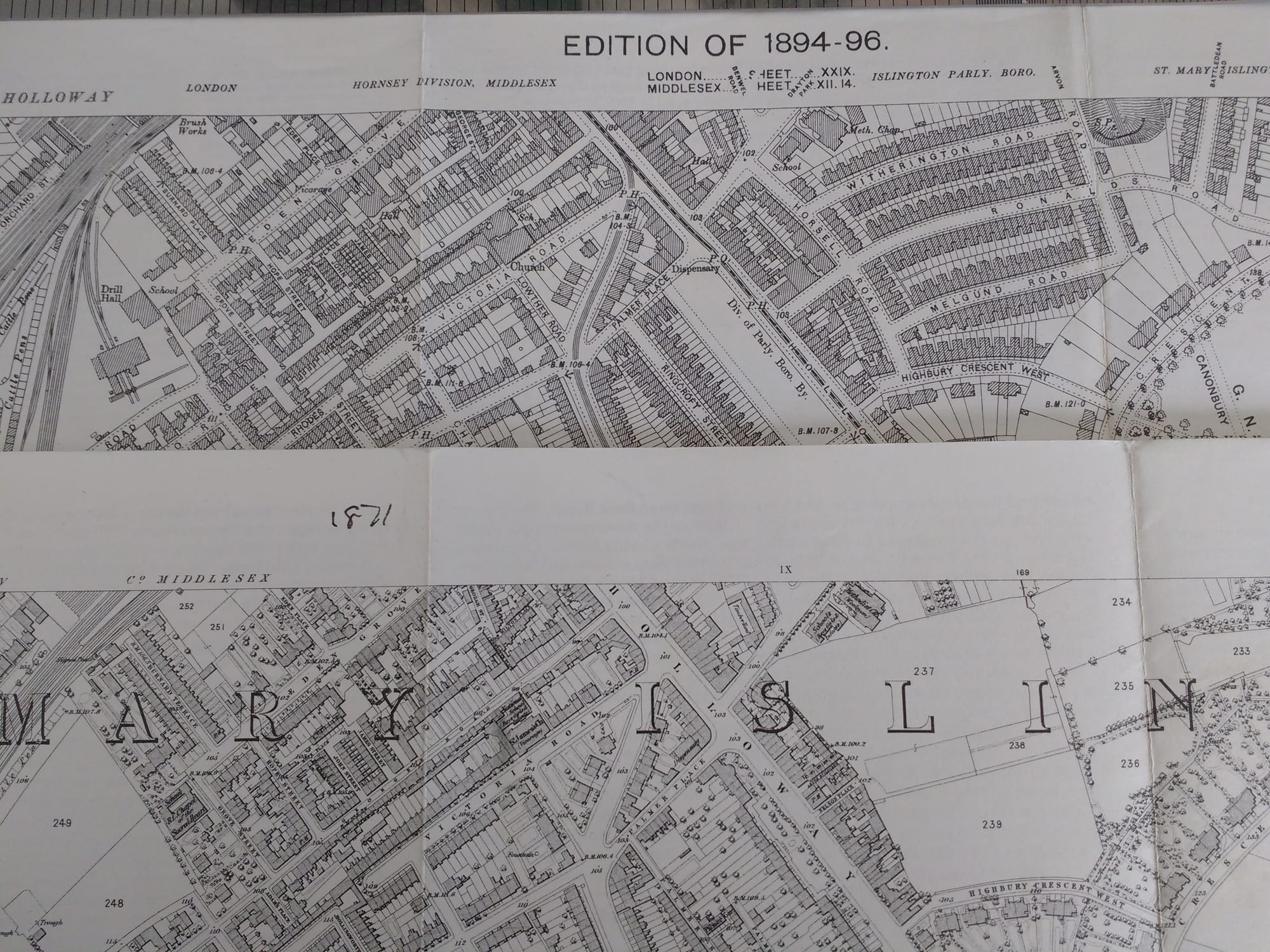

These addresses they moved between are close together, and they were surely short-term rentals; with Raymond's uncertain earnings the frequent moves may have been prompted by difficulty paying the rents. The houses were small, terraced, crowded into new streets built on fields off the main roads leading northwards out of London, as shown by maps of the time. The indications are that they were struggling financially, as were so many; Georges Road was the grimmest, most poverty-struck of the streets in this area, where rents were lowest. Someone born there in the 1940s has written that, even then, the lavatory was a shed in the back yard.

Islington early in the 1800s was a village separate from urban London; the parish boundaries extended northwards with the main northern route out of London ('the Holloway') crossing between fields with only a few small clusters of houses at several points; there was Paradise Row, Paradise Terrace and House near where Eden Grove was built later. Londoners used to journey to this countryside at weekends, and it must have seemed like a rural paradise to them coming from dark and overcrowded city streets. A local historian has written of: "rural Islington... the considerable number of hills... now disguised by the street landscape... With its open country and pleasant streams Islington was regarded as a place for city people to go for a day out... within walking distance."

Comparing an early 1800s map with a mid-50s map of Islington parish shows an astonishingly rapid and near-complete building over of what had been wide, open spaces. As the population of London and its business and manufacuring activity increased, middle-class and well-to-do families were attracted to new housing in this Islington countryside; Eden Grove, Cornwall Place (later to become part of Eden Grove), Georges Place (later Road) and a few other unpaved roads off Holloway Road were made; an 1844 map shows detached houses with open spaces betweeen, gardens behind and then fields, and open ground surrounding this small area. The contrast with an 1871 map is great: more and more people have moved into the area, and building to house them has changed, where once were detached villas or open ground are dense terraces of small houses. By 1871 the appeal of the area had declined. It had become far less like paradise.

"It is difficult to visualise the genteel suburban retreat that Islington had been... lost in the near ten-fold increase in population from [1831 to 1901]. This gave Islington more people than any other borough in southern England - and more than Belfast, or Newcastle, or Edinburgh... "

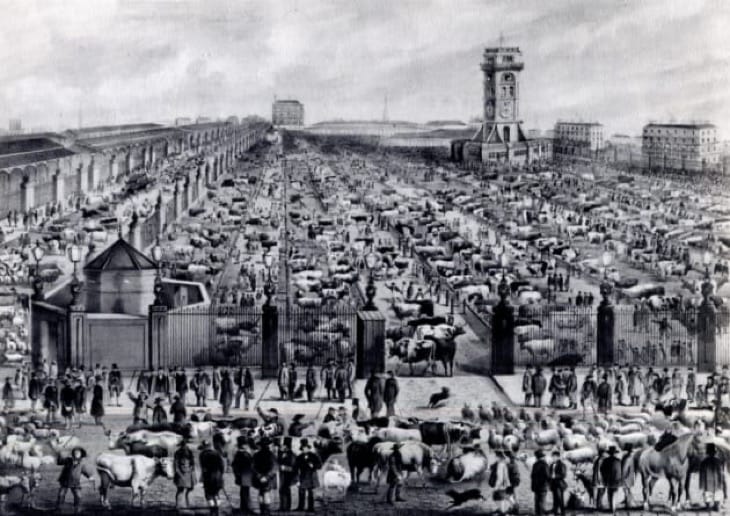

This densification process continued into the last decades of the century, until remaining open spaces had been built over with small terraced houses, railway sidings, goods yards, and the expanding cattle market at nearby, so-called Belle Isle (see Chapter 3). This was the rapidly changing, rapidly densifying area that Raymond and Christina were living in.

Such was the relentless pace of house-building that at the end of the 19th century there was a seemingly sudden realisation that all London's undeveloped green spaces were fast disappearing and a movement was started to preserve those that remained. Green spaces were termed 'the lungs of the city'. This new concern about healthy living conditions and places for recreation was led not by the working people suffering overcrowding, but by a few wealthy and philanthropic individuals - as a result, it was an effective movement and many green spaces were protected from development.

War-time destruction and post-war development has since changed the 19th century character of Islington. Post-war it was regarded as a seedy and run-down part of London, grimy terraces and squares having suffered many years of building neglect; some were replaced in slum clearance by the concrete block-type of mass housing of the 1950s and '60s, a dubious improvement. The relative prosperity of the middle-classes needing to live close to inner London has since rescued the area from further decay and brought about usually sympathetic restoration of old houses, creating 'desirable' Islington.

Eden Grove, St James Street, Chalfont Street and Georges Street where Raymond and Christina lived are shown at the top of the juxtaposed 1871 and 1894 maps (small section of), which show the density of terraced housing and its continued increase over this period.

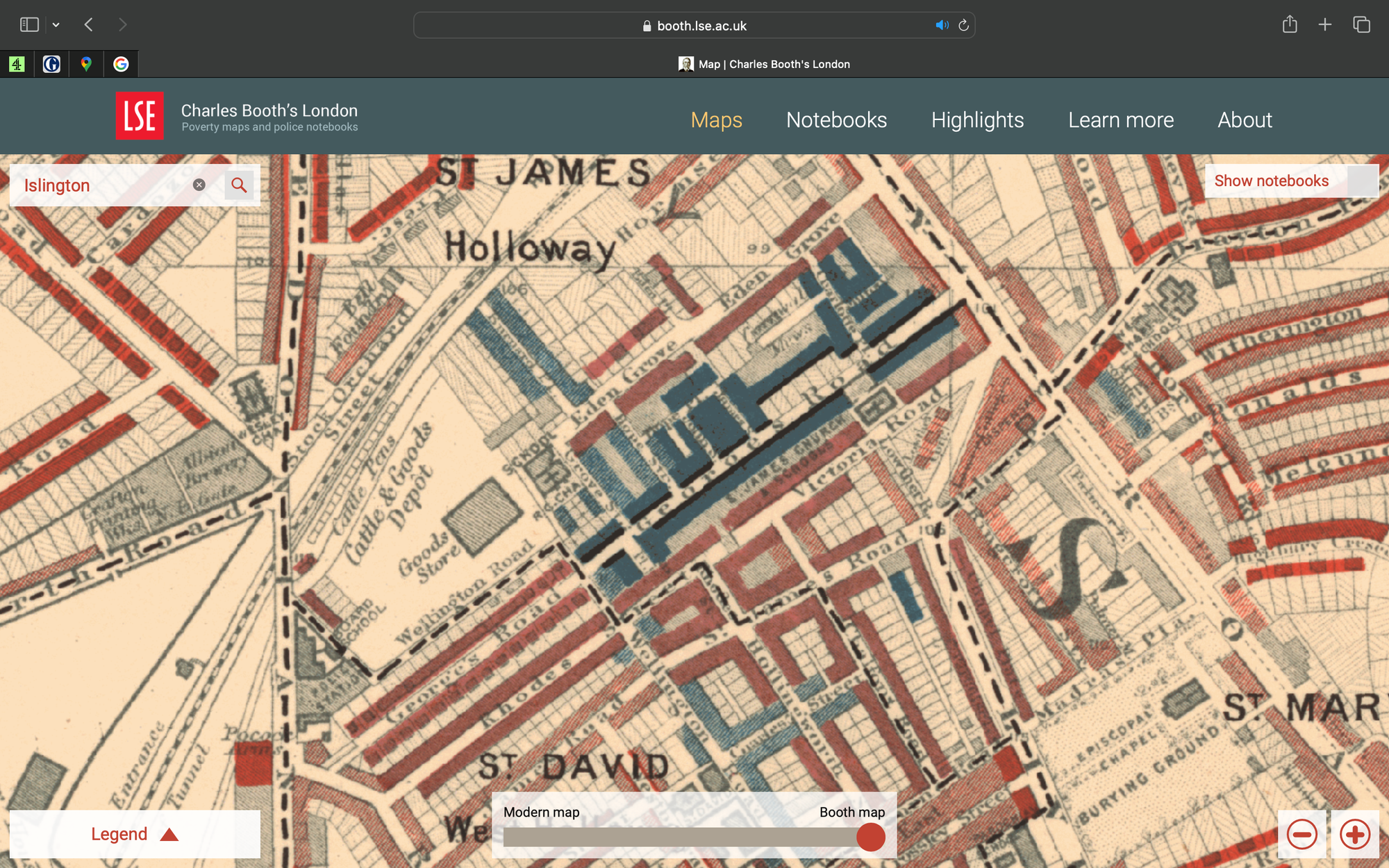

When the family moved to Eden Grove in 1890, the next road parallel to Georges Road, they were moving to a slightly better street, in terms of housing, living conditions and neighbours. In the late 1800s, the philanthropist Charles Booth carried out a uniquly comprehensive and scientific social survey of London life, walking each street and using police reports to literally map, in different colours, the wide variations in wealth, living conditions and social class across London. His mapping included Islington; here, as almost everywhere in London, gradations from extreme poverty to relative affluence lived side by side, with big differences a few streets apart. Georges Road where Raymond and Christina lived in 1889 was coloured black, indicating "Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal" or dark blue "Very poor, casual. Chronic want."; cross-streets and courts (most of which no longer exist) between Georges Road and Eden Grove were dark blue, or light blue meaning "Poor. 18s. to 21s. a week for a moderate family". Eden Grove was purple: "Mixed. Some comfortable others poor."

Isledon Road where Christina had lived before marrying, and Monsell Road likewise for Raymond, were shown in red - "Middle class. Well-to-do" and pink - "Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earnings". In marrying and having children, with only Raymond's earnings to live on, they had really come down in the world. Their move from Georges Road to Eden Grove in 1890 was a small step up.

What Raymond was doing was gradually improving his new family's living conditions, as he had done for his siblings previously. After their son Raymond was born, they moved to more modern accommodation at 281 Farringdon Buildings, Farringdon Road. This was one of several model dwellings schemes in the late 1800s charitably aimed at providing better housing for the 'working poor'; the street numbers were 68-86, so no. 281 may refer to a flat in one of these multi-storey buildings, demolished in the 1970s. That was the address on Raymond's death certificate when he died on 25 September 1892, aged 35, although it states he actually died in St Bartholomews Hospital, London, of “pneumonia and delirium tremens”.

It is unclear what happened to his siblings when Raymond left 4 Scholefield Road. By the next census in 1891 they were not there, another two families had moved in, and the Brooks family they had been sharing with at no. 4 had moved to 22 Scholefield Road to share with a different family. His siblings cannot be identified elsewhere from census records; they were adults, in work, and may have married and/or moved away. But it seems odd that they were not witnesses at Raymond's wedding in 1884, as might have been expected; were they there at Islington parish church? (the banns had been called for three weeks prior - it was not a secret event). Did they know when he was hospitalised? Did they know when he died, attend the funeral, support his widow Christina? And where was his mother, Sarah? I think it is interesting that none of their forenames were given to any of Christina's children before or after Raymond's death, and yet that passing on of first names is so common in this extended family.

What is clear is that the widowed Christina and her children moved back to an area she knew, to Eden Grove, no. 73 this time, where on 4 May 1893 May Frances James was born; on her birth certificate her father was stated to be "Raymond James (deceased)."

How Christina continued is in Chapter 3 following, but she remained as Christina James, surely in fond memory of Raymond, and gave all her children the James surname, including those he could not possibly have been the father of, even if he did father May Frances in the last weeks of his painful, distressing, early death.

Some of the streets where Raymond and Christina lived have been re-named, in what is now the N7 area of London; St James Road has become MacKenzie Road; where Chalfont Road ran north-south crossing MacKenzie Road just a spur remains into Paradise Park (created in the 1970s where a German V2 rocket devastated the terraced housing). Eden Grove remains, as does Georges Road in shortened form. Monsell Road and Isledon Road remain, but unchanged? - hard to imagine a dairy business there now in these traffic bottlenecks, traffic fumes replacing horse dung.

It was not only horses polluting Britain's cities in the 1800s, human waste was a persistent health problem too. In Britain few houses had indoor bathrooms, instead just an outdoor 'privy' in the back yard or garden; these outdoor cesspools were undrained, relying on natural soakage into the soil and liable to overflow. For an isolated cottage in the countryside this would be less of a threat to health (if the water supply was elsewhere) but in cities and towns with crowded housing the risks were much greater. Few houses had an indoor water supply, instead relying on communal water pumps, which might become polluted by leakage from overflowing cesspools. Consuming contaminated water led to recurring epidemics of cholera and other diseases. Chamberpots were used at night in bedrooms, with the contents tipped into the outhouse privy during the day - or just dumped anywhere convenient, as awareness of hygiene was often lacking. By the late 1800s newly built middle-class houses might have flushing toilets, but even grand houses would have had just one bathroom installed near the bedrooms, with servants in the attic or basement still relying on chamberpots. There were exceptions - Liverpool had near-complete provision of water closets in homes by the 1890s. But by as late as 1967 the House Conditions Survey found that 25 percent of homes in England and Wales still lacked a bath or shower, an indoor WC, a sink and hot and cold water taps. One researcher wrote that "I toured a section of terrace-houses in Manchester once that had an interesting layout: there was a square block, and around the perimeter each side had a row of terrace-houses that faced the street. Each house had its own small backyard that backed onto an alley. In the middle of the block - behind all the houses - was a large wash-house, with several (flushing) toilets as well as large laundry sinks and so on. At the time they were built, none of these small 'two up, two down' houses had their own toilets."

Sarah James remains a mystery. If Sarah was 18 in 1854 (as the workhouse records state), she was born before birth registration became mandatory for parents, but there are two relevant baptism records, one for Sarah James, daughter of Catherine James, baptised 20 September 1832 at Launceston St Mary Magdalene, and the other for Sarah Ann James, daughter of William and Grace James, baptised 20 October 1833 at St Germans (which is about 20 miles from Launceston). The fact that the Sarah who was Raymond's mother later had another son she named William (with no father identified) may suggest that his mother was the second of the children above, baptised in 1833.

But either of these Sarahs may have been Raymond's mother, and may have been one of the two Cornwall-born Sarah James included in the 1851 census. This census shows a teenaged Sarah James working for wealthy families with Cornwall connections:

- 17 year old Sarah James (born St Germans, Cornwall) was the still room maid for Edward Granville Eliot, Earl of St Germans, at 36 Dover Street in Mayfair, London; he had a country seat in Cornwall.

- 18 year-old Sarah James was a housemaid for the Cornwall-born widow Grace Williams at 36 Lansdowne Place, Hove, Sussex, which was a fashionable place for retirement. She had three Cornish servants, her cook Saran [sic] James (54 yrs), parlour maid Mary Parsons, and Sarah; their birthplaces are listed simply as Cornwall. After working for Mrs Williams, Sarah could probably have got a job in a well-to-do part of London.

Whichever Sarah was Raymond's mother, it is striking that quite young women were travelling far and wide in search of employment, for menial and junior positions but with the advantage of accommodation and being fed, as part of a large and monied household. This travelling far and wide seems to have been common despite the costs and risks; in the 1871 census when Christina was working at the Tooley dairy in Islington, a visitor is recorded there on the census day, Julia Ann Bridgman, from Barnstable in Devon. They got about, these 19th century girls. It's not the tale of unemancipated females, especially young ones, cloistered at home until safely married, that I had expected to find. They may not have had the vote, but they voted with their feet and made their lives as much as - more than - any of the men in these stories. More to come.

See also Wikitree (free, dates & biography), MyHeritage (subscription, dates)

There is no photograph of Raymond that I'm aware of, probably none taken.

Chapter 3

Christina James

How Christina survived, paid rent, fed her children, is largely unknown and hard to imagine. She had had an impoverished, disrupted childhood, and she did not have a straightforward, settled life after Raymond's early death.

With her three children, Raymond only two but five year old (Mary) Christina and three year old Florence helping perhaps, Christina moved and set up home in the area they knew, Eden Grove, now no longer with a husband and bread-winner. Widows received no pension or other state support. She went back to the street where she had lived with Raymond, where life had seemed to be getting better, before disaster struck.

As Christina's circumstances had fallen, so had this area in the late 1880s and '90s. The numbers of people moving into the area increased year on year, and these were generally poor people, moving out of London 0r migrants from elsewhere (including many from Ireland, so it became a strongly Roman Catholic area) looking for anywhere to live near the employment offered by London and the abbattoir/animal market close to Eden Grove and other industries springing up on the edges of the city. Speculative builders had responded by constructing the mass housing of the time; terraces of small houses were cheaper to build, and many could be built on what would have been the plot of one villa. They were cheap housing to rent, builders' and financiers' investments which could fund more terraces on the next bit of open space.

Much of the local employment came from the extensive slaughter houses and animal pens nearby, into which farm animals were driven and ‘fallen’ horses, of which there must have been many as all transport at the time was horse-drawn. There were trades in using every part of a slaughtered animal, right down to hammering the bones apart; pen pictures of this area of Victorian London are ghastly. The abattoirs and cattle market extended to 30 acres; they were on a small hill under which the railway tunnelled, named Belle Isle, perhaps with grim humour. The proximity of Belle Isle adversely affected the character of the Eden Grove/Georges Road area. The phrase “It stinks like Belle Isle” was used locally, and "the toxic presence of Belle Isle has been cited as a major reason for the decline in the area." From one Victorian account:

"The spot that holds the horse slaughter houses is modestly called 'The Vale;' the first turning beyond is, with goblin like humour, designated 'Pleasant Grove.' It is hardly too much to say, that almost every trade banished from the haunts of men, on account of the villanous smells and the dangerous atmosphere which it engenders is represented in Pleasant Grove. There are bone boilers, fat-melters, chemical works, firework makers, lucifer-match factories, and several most extensive and flourishing dust yards, where - at this delightful season so excellent for ripening corn - scores of women and young girls find employment in sifting the refuse of dust-bins, standing knee-high in what they sift.”

The streetscapes in this area have gone on changing in the many decades since the late 1800s. It is not just the traffic congestion that makes it near-impossible to imagine the original semi-rural attractions of Eden Grove and where once was Paradise Row, House and Terrace, or to see the later densified, terraced street that Christina first lived in at no. 57 and returned to after Raymond's death, at no. 73. There she gave birth to May Frances James on 4 May 1893, who may or may not have been Raymond's daughter.

Then Christina started a new relationship, with Charles Waller. He was not a local man - he worked as a live-in footman in Mayfair in central London in 1891 - so how they met is not obvious. Later he had a better, live-in job as a 'domestic coachman' at a posh north-west London household in Hendon, as noted in the 1901 census; he may have had this job by the time he had met Christina, or another in one of the big houses on Tollington Park Road.

He was four years younger than Christina; whatever degree of attraction there was on her part, she needed financial support. No marriage record has been found but she may have hoped to marry him, as she presented herself as "Christina Waller late James formerly Potter” when registering her fourth child’s birth in October 1896, and named their baby Charles Edward after the father. He was born at 39 Lennox Road, near Finsbury Park, so while Christina and Charles were in this relationship she had moved to a better house in a better, although mixed, area.

But, Charles Waller already had a partner, Isabella Waller (no marriage record can be found despite her surname), who he continued to live with for many years after knowing Christina. At what point did Christina know he was already in a relationship which was, or was presented as, marriage? As a footman then coachman in large private houses, he would have had the perfect excuse for not moving in with Christina (nor with Isabella at the time, who he did not share an address with until much later). Conveniently for him, a local train would have quickly got him from where he lived and worked to Finsbury Park station, which may be the reason Christina went to live at 39 Lennox Road nearby, i.e. he arranged this. However, that did provide her and the children with better housing in a rather better area, and how else could she have achieved that? It may be that his relationship with her was fairly serious on his part and lasting several years.

His son, Charles Edward, was only known by the Waller surname on his birth certificate, and probably never himself knew that his surname was any different to his siblings. The oldest daughter - referred to here as '(Mary) Christina' to avoid confusion - and Florence would have known and remembered, aged nine and seven respectively. But perhaps knowledge of the Waller episode was lost in what followed, and the further desperation, deception and escaping that went on.

By March 1899 when her last son Robert was born (and registered with the long-deceased Raymond James stated to be his father) Charles Waller was off the scene; this is likely, because by then Christina and her children were no longer in the fairly decent house in Lennox Road but had sunk to much lower housing.

On Booth's poverty maps Lennox Road is purple - "Mixed. Some comfortable others poor". But it crosses Campbell Road, all of which is solid black, on both sides: "Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal". So when Charles Waller left, Christina had only to turn a corner to fall into one of the worst slums in London, that's how mixed up and side-by-side misery and comfort were in London in the 1890s.

Christina and the children were living at 90 Campbell Road when Robert James was born. This was a slum of the direst poverty, rife with criminality and prostitution. House-building there started in the 1860s but paused often, meanwhile the street remained unpaved and unlighted, used as rubbish dump, with the result that social decline set in from early on, the six-room houses intended for clerks being taken over poorer tenants. Campbell Road had a reputation as the worst street in North London. "Doing a Campbell Bunk" was local slang for for 'getting-away-with-it' - some crime or misdemeanour.

"Its social decline.... was hastened from the early 1880s, when a large building intended as a public house was registered as a common lodging house for 90 men. Many houses were sold because of difficulties in repaying mortgages and several also became lodging houses, which drew a rough and shifting population, whereupon most respectable residents left... Residents in the 1890s did casual work or were thieves or prostitutes, and roughness was increased by London slum clearances from the 1870s... After the Second World War Campbell Road (renamed Whadcoat Road in the 1930s) was one of the first streets to be demolished... it was removed entirely to provide the site for flats..."

"By 1890, Campbell Road had the highest number of doss house beds on any Islington street. The residents, facing extreme poverty and overcrowded conditions, often spilled onto the streets. The area gained notoriety for its dire conditions, with inhabitants resorting to selling window glass and the police avoiding the neighbourhood due to its lawlessness. It became a hub for career criminals, marked by insularity and territorial rivalries... Campbell Road residents hesitated to disclose their address, fearing job discrimination, especially for positions in the numerous small factories in Islington..."

Who was Robert’s biological father is unclear, as is when Joseph Hicks appeared on the scene. He and Christina married on 22 October 1899, both giving 301 Bethnal Green Road, London, as their address (so cohabiting? an escape from Campbell Rd). She is listed as Christina James, widow, aged 34, her new husband as Joseph Hickie, mason, aged 36, his father as George Hickie, deceased, mason; Christina signed the register, Joseph X'd it. The marriage certificate misreads Hicks, on the signed register, as Hickie. Joseph Hicks' birth certificate confirms these details.

The 1901 census lists the new Hicks family at 4A St Loys Rd, Tottenham, London, with almost all details matching the James birth certificates, except that Christina James gave her name as Christina Hicks aged 38 (so born circa 1863, as she was) in Glasgow, and all the James children's surnames are given as Hicks: Florence Hicks 11, Raymond Hicks 10, Mary Hicks 7, Charles Hicks 5, Robert Hicks 2; the children's ages match their birth certificates, except for the eldest Mary (Mary Christina) who would have been 13. Husband Joseph Hicks was listed as a stonemason age 42 (so born circa 1859, in Hoxton).

This may have been an escape from the clutches of the Campbell Road slum for Christina, but 4A Loys Road was a small, very basic add-on to the house next door. Was Joseph a loving and supportive new husband? My uncle George (born 1907, one of Christina's grandsons) told me, after I traced him just before he died, that Hicks was a workshy drunkard (and violent?), so not providing the support Christina needed and probably awful for her and the six children to live with. Eventually she decided she had flee from him with the children.

Uncle George said that when the three sons came to be married much later, in Scotland, they worried that they might be illegitimate, but their mother reassured them that - "oh no, I did marry him". So although the boys were very young while all these changes of homes and partners were going on, with emotional disturbance that can only be imagined, they retained some memory of those disrupted times.

However, Christina kept it together. Somehow, she squirelled together the train fares and packed what was carry-able by her and the older children, bearing in mind the two youngest boys probably had to be carried, all of which preparation must have been difficult with new husband Joseph in the house and not working. Just getting them all away from the house and to Euston or Kings Cross mainline stations must have been difficult. Finding out train times and booking tickets may have involved a prior (and secret) visit to the station, or did they all arrive there to wait for the next outgoing train to Glasgow?

Having lived near the main railway lines close to Eden Grove, escaping by train would have easily occurred to her. But why to Scotland? - a long distance therefore expensive and a trial with the six children, and surely she had to overcome bad memories of her childhood in Scotland - after all she left for London as soon as she could as a young teenager; she must have been hoping for family support there.

At the time adult fares were 1 penny per mile, so about £2 London to Glasgow per adult; half-fares for children under 12 years, so the three oldest children would have needed adult tickets. I have not compared these fares with average wages of the time, because Christina’s family seems to have had no regular income, average or otherwise. After she had made the decision to leave Joseph, surely there was quite a long time for her to save up the rail fares from what were very meagre resources, if Joseph was not working but was getting drunk.

They travelled some time between the 31 March 1901 census and May 1905 when Christina was recorded as a millworker at Deanston cotton mill in Scotland. They must have arrived in Glasgow before this, staying with her brothers or sister Ann Marie (themselves with children and small houses), while looking for work and housing. She spent the rest of her long life in Scotland, but not in Glasgow with her relatives. Her 'adventure' continues in Chapter 4.

Widows received no pension or other support in the 1800s; they were expected to re-marry, and many did, even if there were supportive relatives with resources beyond their own needs; most widows with children had no real choice - find a husband, or what? prositution?. The early death of a husband was a common occurrence, through work-accident or ill-health often related to working conditions (in which modern notions of safety were absent) or chronic malnutrition. Women worked as well (earning much less than men) and were also at risk, and from the complications of childbirth. As a result, marriages were seldom lengthy, and the vow 'til death do us part' had a reality and present-ness we may have forgotten today. Marriage was functional and necessary for survival for most people; it was not a love story, not primarily the emotionally intimate relationship expected of it today; it was a practical and economic partnership above all, and without it working in that way the slide into poverty was rapid.

Charles Booth was a successful business man and philanthropist, who became interested in the wide disparities of wealth and poverty in Britain's cities in the late 1880s. His Inquiry into the Life and Labour of the People in London (1886-1903) included Maps Descriptive of London Poverty, in which each street is coloured to indicate the income and social class of its inhabitants. In most areas, streets of poverty were found close to comfortable middle-class affluence; the social and economic gradations were very mixed geographically. The seven classes are described on the legend to the maps as:

-

Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal. BLACK

-

Very poor, casual. Chronic want. DARK BLUE

-

Poor. 18s. to 21s. a week for a moderate family. LIGHT BLUE

-

Mixed. Some comfortable others poor. PURPLE

-

Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earnings. PINK

-

Middle class. Well-to-do. RED

-

Upper-middle and upper classes. Wealthy. YELLOW

In Islington, Georges Street where Raymond and Christina lived in 1889 was coloured black; cross-streets between Georges Road and Eden Grove were dark blue, or light blue; Eden Grove was purple. Bethnall Green Road was mostly coloured to indicate mixed, some comfortable others poor, streets behind the main road were dark blue or black - lowest class/very poor/chronic want. Farringdon Road was similar. Tottenham and St Loys Road were outside the area Booth surveyed, as was the eastern end of Lennox Road.

The Metropolitan Cattle Market closed in 1939 and was sold off, most of the site becoming multi-storey blocks of flats, public gardens and sports grounds; only the original clock tower remains. In fact, Belle Isle had a (non-ironic) French origin. By 1842 Peter Henry Joseph Baume had established 'Experimental Gardens' on part of the land, also known as the Frenchman's colony or Island, on the communitarian principles of Robert Owen. Baume let small plots on which poor people could build, and he built cottages for sale or letting. In 1851 it was inhabited by 48 families of craftsmen and labourers; the buildings had disappeared by 1853. In 1848 sanitary inspectors found that both Belle Isle and Experimental Gardens had filthy cottages with open drains.

A detailed account of the development of Islington is at https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol8/pp29-37.

It was a shock to discover eventually, after not finding any birth record for a Charles Edward James, whose date of birth I had from his death certificate, that when born he was named as Charles Edward Waller. In all that followed, I have found no later reference to the Waller surname. I think I would not have written about it here if any of that generation or the next were still alive.

The mystery of the disappearing May Frances James may have been solved belatedly. She is nowhere in the Scottish 1911 census, but she does appear in the 31 March 1911 census of England & Wales, thus:

"May Frances James, age 17, born circa 1894 in Holloway, London, single" - all of which is correct, and it is very unlikely there was another young woman with identical identifiers. But, where was she living/working? - at 14 Buckingham Palace Gardens, with a German governess, a German visitor on the day of the census who was a masseuse, and ten servants of which she was the youngest, a woman who was in charge and listed as if head of this household, which surely was a royal household. Mystery solved, but in an astonishing way. Did May Frances remain in London when her mother and the other children left for Scotland? - but at the age of eight (if they left in 1902) that seems unlikely and where would she have lived meanwhile? None of the other names in this household have been noted previously in relation to the James/Hicks family, so it doesn't seem that a friend got her a job there. To take up this junior servant job she must have gone back to London within a short time of arriving in Scotland, travelling alone, aged between 12 and 16 years, with the rail fare afforded somehow. For what purpose? If it was to train as a nurse or midwife (her occupation was given later as maternity nurse) in her spare time, it might have been at Guys Hospital, about four miles away across the Thames.

Chapter 4

Stirling

Christina James soon obtained a job and accommodation for her family outside Glasgow, continuing to make her way in life independently of her relatives there. She and the children made another journey, a shorter one, to Doune in Perthshire and then to the nearby milltown of Deanston; there was a Glasgow-Stirling rail link, with an intervening station several miles from Doune. In mid-1905, aged 42, she was living and working there, recorded on Scotland’s valuation roll of that year. This is a local property tax assessed every year, recording the owners and occupiers of almost all buildings in Scotland and the rents paid by tenants.

Mrs Christina James is listed as a millworker, and a tenant of First Division at The Cotton Mill, proprietor James Finlay & Company, manufacturers, at Deanston, Kilmadock (parish), Perth (county). This was company housing for its workers (there was also East Cottage, West Cottage, Second Division, each with many tenants listed). Christina was paying £5/4 (shillings) per year. Valuation rolls list only the head of household, unlike censuses which list all occupants, therefore all the children were probably living there with her in May 1905. Christina’s oldest daughter (Mary) Christina also obtained work there; in December 1907 when she gave birth to George Edward James, (Mary) Christina was noted on the birth certificate as a cotton weaver (the Mary forename was omitted) with her address as Deanston; present at the birth was "Christina James grandmother”.

Deanston looked grim to me when I visited, a small village dominated by the mill buildings and workers' housing, at the end of a side road from Doune, and not somewhere you'd stay and make your life if you could think of alternatives.

Florence Maggie and some of other children probably also worked at the Deanston cotton mill; child labour was common and in poor families everyone who could work did so. The legal minimum working age (often disregarded) was only 12 years; Florence would have been 18 in 1907, Charles Edward just turning 12, and only Robert, 8, legally too young to do paid work.

Christina's eldest daughter (named then as Christina Mary James) married George Ross on 8 October 1910; as a witness to the marriage Christina gave her name as “Christina Hicks previously James m.s. Potter”, the only time apart from the 1901 census in England that she gave the Hicks surname. The marriage took place in Glasgow.

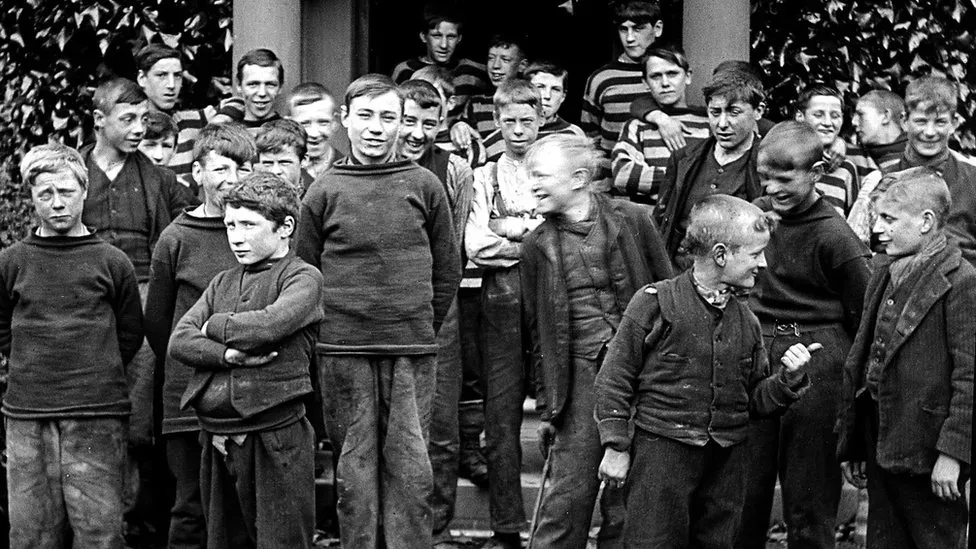

It's probably no mystery why Christina chose not to spend the rest of her life in Glasgow, where she had been born. Living conditions in Glasgow remained poor, overcrowding and inadequate housing had little improved since she was born there. So bad were conditions in many of Britain's industrial cities that from the late 1860s there had been a migration scheme for children orphaned, abandoned or just from impoverished families, to be shipped en masse, as cheap labour, to the dominions - Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and other parts of the Empire; over 100,000 children had been sent away by the time this scheme (there were others) ended in 1940.

This is a group of 'surplus' children from Glasgow gathered at a farm preparatory to being shipped to New Brunswick in Canada where the farm-owner had another land-holding.

Christina chose to set up home, for the rest of her life as it turned out, in the much smaller city of Stirling; this was about eight miles from Deanston. Stirling had a population of about 18,000 in 1900, compared with Glasgow's 750,000. Following a cholera epidemic, sewers had been dug under the streets of Stirling in the 1850s; it was far less overcrowded and unsanitary than Glasgow. As well as being a port city, on the river Forth which runs eastwards, it was surrounded by rich farmland and relatively prosperous. Stirling was probably a more pleasant, less pressured place to live her new life for Christina, and without reminders of bad memories.

By April 1911 Christina was living at 10 Viewfield Street, Stirling, age 47,with three of her children (Raymond, Charles Edward, Robert) and her four year old grandson George Edward. The oldest child, (Mary) Christina, George Edward's mother, had moved to Helensburgh without him after marrying; Florence Maggie had gone there with her older sister. It is unclear where May Frances was at this time. In the census Christina was described as a "monthly nurse". In the 1921 census, she no longer had an occupation listed; she was 58 years old, and was noted as "H.D." as were other older women, perhaps signifying 'home domestic'.

She continued to live there through the First and Second World Wars. Over the next 45 years it became her permanent family home, perhaps the first security in that sense that she had had in her life. Son Raymond was there with her except during the First World War. After marrying, Raymond still lived there with his wife and children, and the other sons stayed there much of their adult lives, as did May Frances James.

No. 10 Viewfield Street is a three-storey inner-city house on a narrow street, with side access. It is multi-occupancy; there were eight tenants in 1915, around 20 tenants in later years, mostly men listed as joiner, clerk, engine driver, mechanic, painter, bootmaker etc, women simply listed as Mrs... Tenants paid rents rising from £8 per year in 1914 to £14 in 1940. Each tenant and dependents occupied one or at most two rooms; there would have been one lavatory/bathroom for the building. Today it has eight flats, and now has 2 windows in the roofspace which may be recent providing additional space.

Florence Maggie James moved around, as had her mother. She is noted in the 1911 census as age 22 living at Dungoyne House, Colquhoun Streeet, Helensburgh, as a "table maid domestic". She married on 30 December 1915, age 26, a table maid, of Tillicoults House, Tillicoults, Clackmannanshire, to Robert Henderson, a chauffeur and private in the Royal Highlanders, at 2 Wolfcraig, Stirling, in an 'irregular' marriage in the presence of May Frances James, domestic servant, and Robert James, rubberworker, both of 10 Viewfield Street. In 1921, Robert Henderson was employed as a gardener at Graymount, a mansion in Bendochy, Perthshire, living in Graymount Lodge with his family; they had a daughter, Christina (again!) born the previous year. Florence Maggie Henderson lived until she was 94, dying in 1983 at Bowerswell Memorial Home in Perth; she was described as the widow of Robert whose occupation had been insurance clerk; her son Robert was the informant of her death, and gave her parents as Raymond James, stonemason, and Christina James m.s. Potter.

May Frances James's life after arriving in Scotland is a mystery. She is missing from the 1911 census altogether. In 1921 she was at 10 Viewfield Street, age 28, her occupation being "maternity nurse". She does not appear at any address as a tenant or owner/occupier in the five-yearly valuation rolls and later census records are not available, so it may well be she continued living under her mother's tenancy at 10 Viewfield Street. That she is named on her mother's gravestone with the James surname suggests that she did not marry. May Frances James lived until 28 August 1977 when she was aged 84. She died in the Royal Infirmary in Stirling, of "hypothermia, cerebro-vascular accident and bronchopneumonia", which leads me to wonder if she had been living alone in her last years; her address is given on the death certificate as 14 Newhouse (Road), Stirling; this address is now a relatively modern block of flats. May's brother Charles Edward informed the registrar of her death.

When her death was registered her occupation was given as "certified midwife (retired)". Her parents were stated to have been Christina James m.s. Potter deceased and Raymond James, coachman, deceased - this was the only later occasion when Raymond's occupation was stated correctly, rather than incorrectly as stonemason as on other death certificates; presumably Charles Edward provided this information; he died seven years later.

This photograph, passed to me years ago by a cousin, Uncle George's youngest daughter Anne, is of Christina's daughters, (Mary) Christina who I do recognise, she was my grandmother, and probably May Frances and Florence Maggie - which is which I am unsure; the photo is not labelled. They seem to be middle-aged so it was probably taken in the 1930s, when I know they were not living near each other but for some occasion got together and were photographed. I see a definite family resemblance between them and Christina in this photograph, date unknown to me.

Unlike her two eldest daughters, Christina's sons stayed living with her or nearby in Stirling most of their lives. They may well have contributed to her rent and living expenses after she stopped working, but from their modest jobs, as noted on census records, family finances were surely tight.

Christina would have started to receive the new state pension only in 1933 when she turned 70; this was introduced in 19o9, a great innovation, albeit a paltry amount (between 10p and 25p per week) compared with today's (also inadequate) state pension. Widows received no support until 1925; war-widows, of which there many, started to receive support during the First World War.

Christina lived her the second half of her life through a time of much change; before she qualified for the new pension she would have been given the vote, previously denied to women. This right was introduced in 1918 for women over 30 years who were also property-owners or married to one, and changed in 1928 to the same as for men: over 21 years with no property requirement. Much good it did her. In Britain, following the slaughter of so many young men in the First World War, the 1920s and '30s were times of economic depression, strikes, mass unemployment and hunger marches. Inflation increased prices of everyday goods just at a time when earnings sank for many; the pound was devalued by 40 per cent in 1921. As of that year, Raymond and his brothers still had jobs - the same as previously, suggesting no promotion or progession in earnings - but whether they continued to be among the fortunate few hanging onto employment is unclear, as the 1931 census records were destroyed.

Charles Edward James is in the 1911 census (with Edward omitted) at 10 Viewfield Street as age 15 and his occupation recorded as"Brushworks." In 1921 he is at the same address, age 25, as a motor driver. On 27 June 1923, still a motor driver living at 10 Viewfield Street, he married Mary Chalander Samson, a bakers saleswoman, of 14 Well Green, Stirling; he was 27, she was 31. It was a 'regular' marriage, with banns called. A witness was Robert James, still living at 10 Viewfield Street. In 1925 he was a tenant at 8 Shiphaugh Place in Stirling, presumably with his wife; he or they were still there in 1940, "no. 8, house and garden, Shiphaugh Place". Did Charles and Mary have any children? The photograph below suggests they had one son, but...

This is the only photograph I have of Charles as a youngish man (or of any of his siblings before they were elderly), and it is yet another mystery. On the back was pencilled, by Charles' nephew who was my Uncle George (born 1907), "Helen & boy & uncle Charles only son & mum". They look happy, good. To my Uncle George, "mum" on the left was (Mary) Christina Ross. However, who was Helen? From the hands resting on shoulders, this could look like father-mother-son but Uncle Charles married Mary Chalander Samson. The only Helens were in the next generation, and Helen King James, daughter of Charles' brother Raymond, was born 1916, making the date of this photo late 1930s. Were women then wearing dresses of that length then? Nice photo, but a mystery.

Charles Edward James lived until 26 March 1984 when he was 87 . Described then as a retired van driver, he died at Bellsdyke (a psychiatric hospital), Larbert; he had been living at Batterflatts, Stirling. The informant was R. G. (initials unclear) James, son, of 2 Forrest Road, Stirling.

Raymond James, Christina's oldest son, when living at 10 Viewfield Street with Christina in 1911 had an occupation shown on the census as "India Rubber Work". On 12 October 1915, named as Donald Raymond James, age 25, rubber worker, lance corporal 6th Battalion Middlesex Regiment, of 10 Viewfield Street, he married Jemima Catherine Fraser, a typist, age 24, of 16 Guys (?) Road, at 2 Randolph Terrace, Stirling, in a 'regular' marriage, after banns were called; Charles Edward was a witness. The couple went to live at 10 Viewfield Street and were there in the 1920-21 valuation roll, with Raymond listed as a separate tenant paying a different rent from his mother; he is listed as still being a soldier. In the June 1921 census Raymond is at the same address, giving his name as Donald R. James, a "machine hand (tyre & hose)" with wife Jemima and their three children Helen King James 5 years, Christina Potter James 3, and May F. (Frances or Florence?!) 2 months, all born in Stirling; King was Jemima's mother's maiden name, and Potter was, of course, Donald Raymond's mother's maiden name, so care was being taken to make and respect generational links. In 1926 they had a son, Donald Raymond James, and in 1928 another, Edward Charles James, both born in Stirling; more family-linking by names (but it gets so confusing).

Over the years Raymond had decided to be known as Donald Raymond James, with the middle name sometimes just an initial. And passed on boith names to his first son. His birth certificate named him Raymond, the birth register as Donald Raymond. Who on earth was this Donald? Added to this mystery, is another, stranger: Christina's older sister had married Daniel Connal who part way through his life, in London, also started calling himself Donald Connal, and gave that forename to his son. Coincidence? But we don't know where that Donald came from either. This Donald Raymond and that Donald Connal were related as in-laws, obviously, but did they ever meet? Is there a shared Donald ancestor?

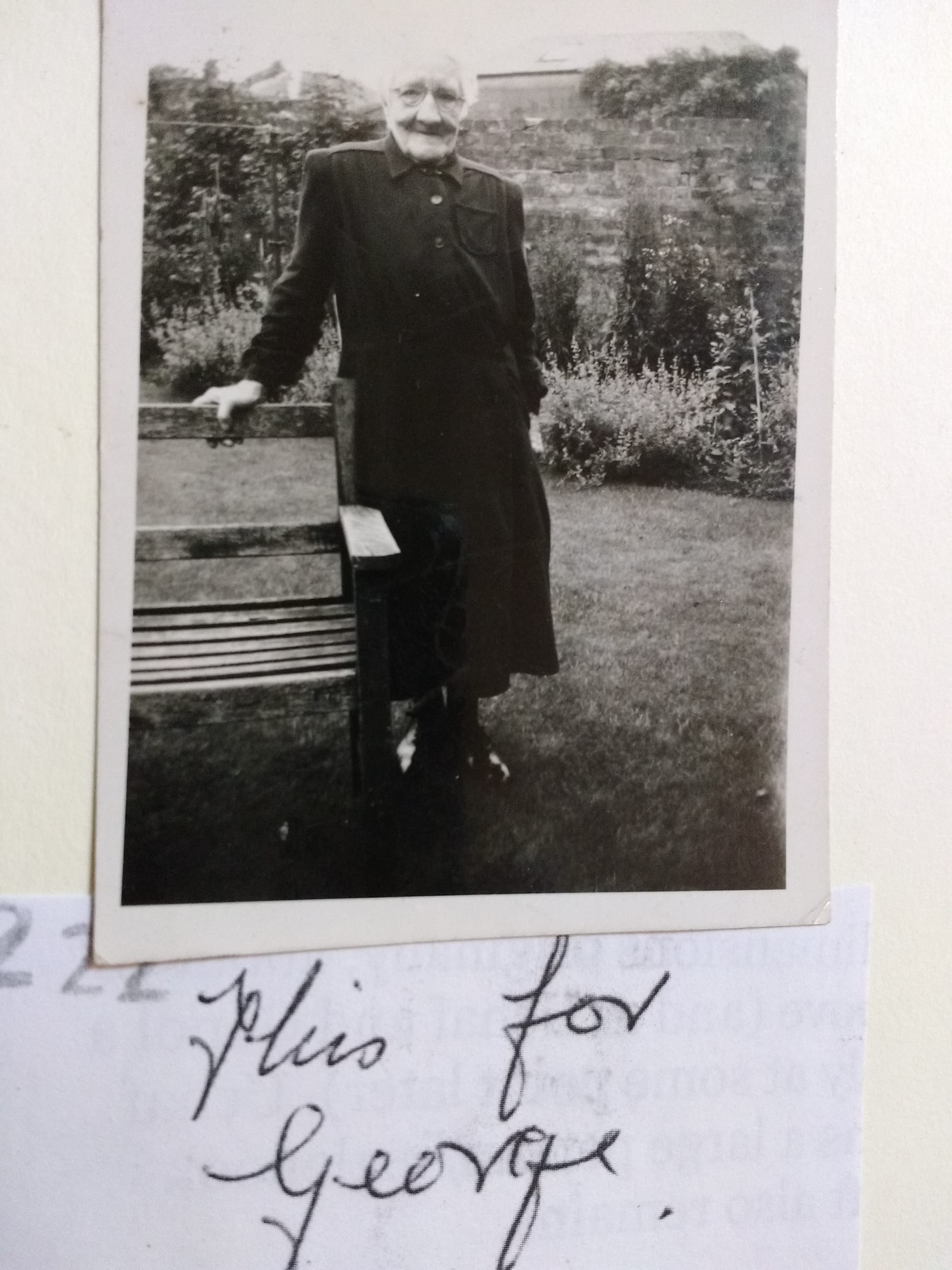

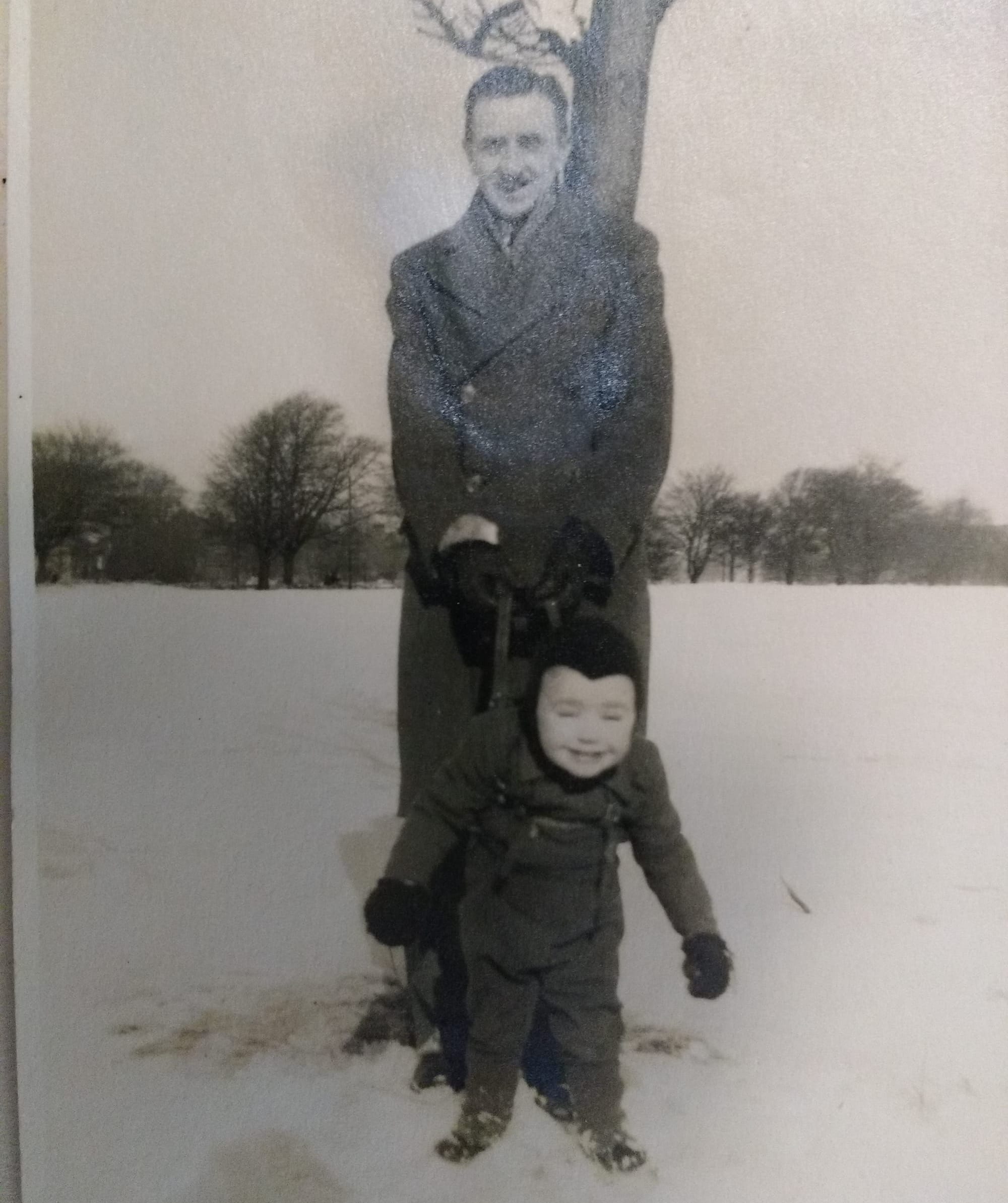

In the 1925, 1930 and 1940 valuation rolls Raymond, still a rubberworker, and presumably his family were still at 10 Viewfield Street, and lived there until he was 73. He died, named as Donald Raymond James, on 3 July 1963. As the oldest boy, he took on the dutiful role of 'man of the family', living with his widowed mother or when married in the next flat, all his life. Here he is, an elderly man with an even older mother. The writing on the back says: "Brother Raymond, his sister and Mother xxx"; the sister is probably May Frances James; the photograph may have been taken at 14 Shiphaugh Place, which had a garden, and Raymond's brother Charles lived there until at least 1940. The second photo probably includes Raymond's wife Jemima and daughter Helen, so about mid-1920s.

Was Christina also "hard on her boys", as (Mary) Christina her oldest daughter was later said to have been (see Chapter 5), possibly a female family pattern? After all, she had not had much luck with the men in her life previously. But in these photographs she is surely taking pride in having her children and their children around her.

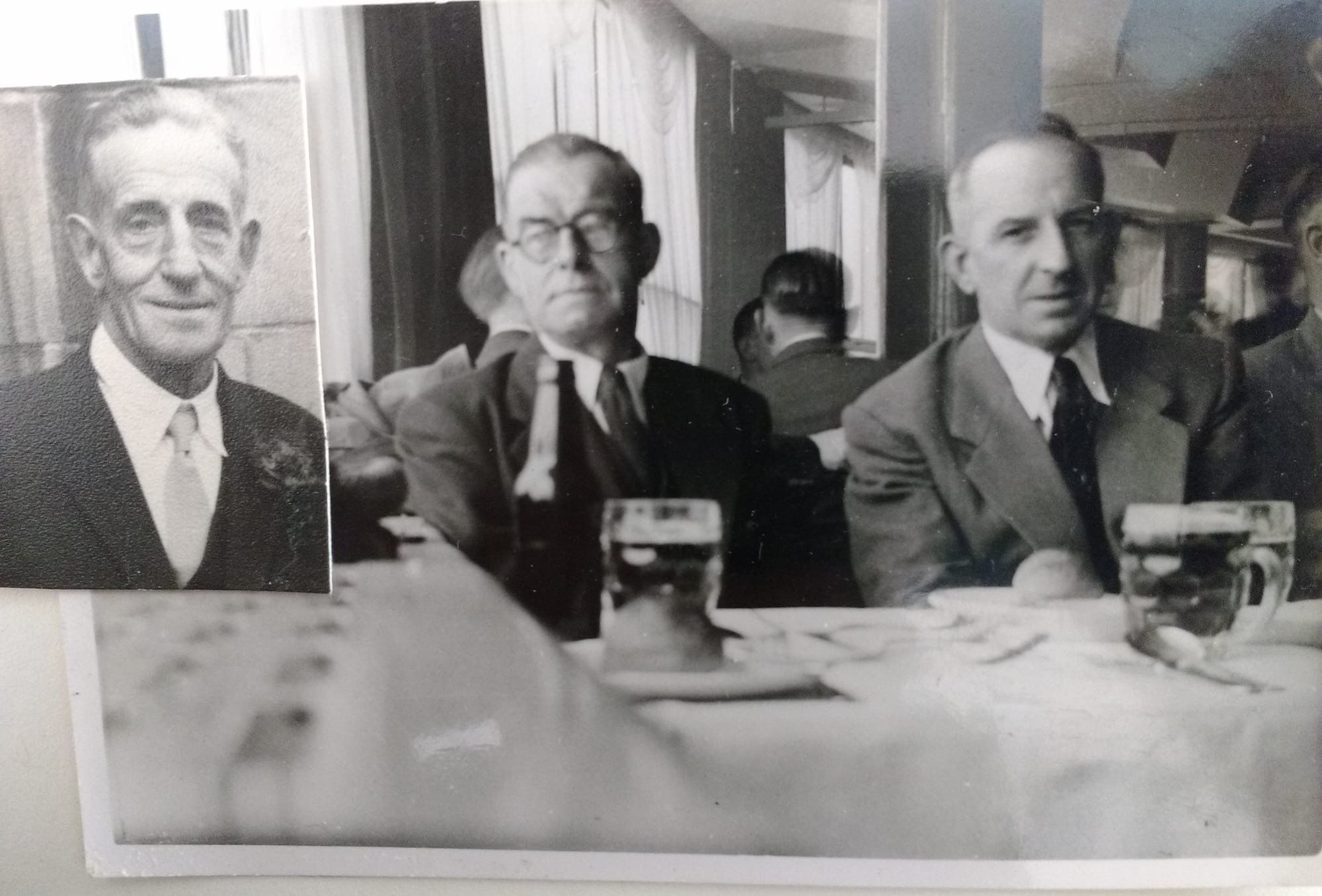

These are her three boys. To this photograph of Charles Edward and Robert in a pub, I have added a more elderly Raymond on the left. They all look to me as if they've come through a hard life, the disrupted childhoods in London, scraping together a living in difficult times in Scotland, living with or close to their mother, looking after her. They have been dutiful, and there's a dignity to Raymond. Interpretation, of course. They certainly haven't wandered far and wide, and maybe not felt free to do that, as two of their sisters did. They are a few years apart in age, had different fathers, but similar experiences have brought them to the same place in old age (and I don't mean Stirling). Near the end of ther lives they are together, which counts for a lot.

Robert James, Christina's youngest in 1911 was age 13 and shown as still at school on the census at 10 Viewfield Street, and was there in 1921 age 22 as a motor driver like his brother Charles; in 1923 he was still there with his mother. In 1914 he would have been too young to be involved in the First World War, and by its end in November 1918 he'd have been just old enough (many boys lied that they were old enough to join up); in the last year of war, men and boys were still being conscripted and thrown into the slaughter. Many families lost a fathers, brothers or husbands; towns and villages have memorials listing name after name from the same local families. In trench warfare there were many days when thousands died in a single day; the heaviest loss of life for a single day was on 1 July 1 1916, when the British Army suffered 57,470 casualties in the Battle of the Somme. All three of Christina's sons were fortunate to have survived the First World War.

On 16 November 1928 Robert married Isabella Frances Barnes Robertson at St Ninians; he was 28, she was 38, a "clerkess" of Dowan Place, Cambusbarron; both places are villages near Stirling. It was a 'regular' marriage with banns called. None of Robert's family were witnesses. Robert and Isabella then lived at 38 Scott Street in Stirling in 1930 and 1935 (the valuation rolls give no more identifying information). In 1940 Robert (and Isabella?) was at 38 Scott Street, Kincardine (about 12 miles from Stirling), where he stayed for the rest of his life. He lived until he was 81, dying on 3 Novmber 1980, described as a retired storeman, at the Royal Infirmary in Falkirk. The informant of his death was Andrew Guthrie, son in law, of 23 Lansdowne Crescent, Kincardine, so it seems that in his last years he was living close to family.

All Christina's children lived long lives, the three boys survived the First World War which tore apart so many families, all of them survived the post-war influenza epidemic, two of the girls found husbands, had children and made their lives independently elsewhere, Perth and Yorkshire. May Frances James's long life remains a mystery.

They were alive when I was in my 30s and 40s; had I known of them, had there not been such family silences, I could have met them, I would have memories of them now.

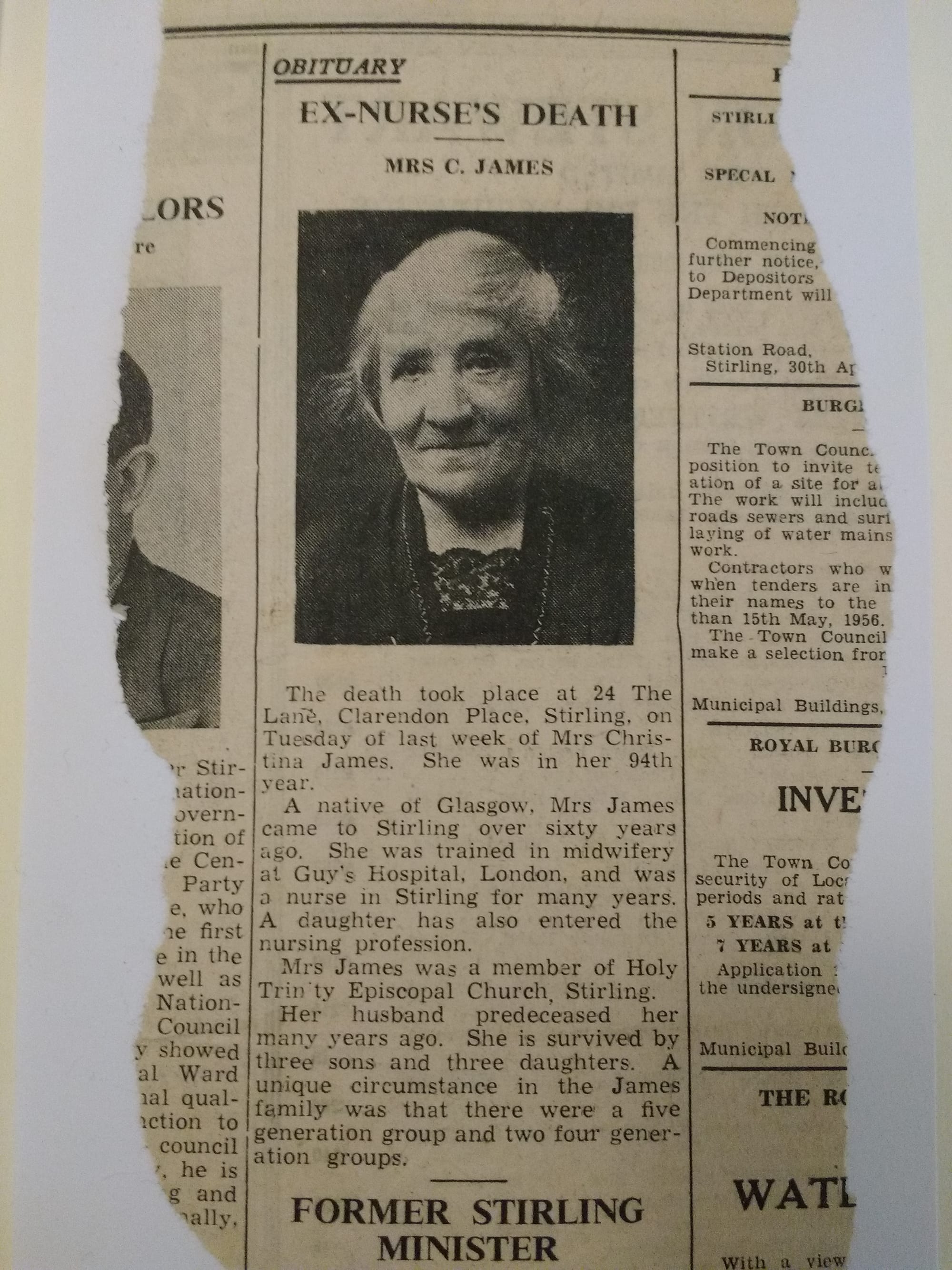

They all outlived by many years their long-lived mother. Christina died aged 93 on 1 May 1956, at The Lane, 24 Clarendon Place, Stirling. My Uncle George, one of her grandsons, who she had cared for as a little boy, told me they (his siblings) called this place “the hole in the wall” (so, a squat?), and said that it no longer exists. She intended this photograph to go to George Edward Ross; it came to via his daughter Anne.