Not So Long Ago

It was very different back then, less than a lifetime ago, like a foreign country. Do they know this, my family? I start to tell them a few things, they laugh and are surprised. I can tell them more, it gets stranger still.

This started in a café by the sea, a small group of us. As we talk my daughter is fiddling with her iPhone, she takes a photo of us then says it’s so hard to get photos off her phone. I say, but it’s a phone that can take pictures, better than a party-line! My wife grins and nods, the others are mystified, a what? a phone just to get invitations to parties? My daughter is not a youngster, she’s in her 50s but she’s never heard of party-lines.

Life was quite different not so long ago, how people lived, the details of everyday life. The past is a foreign country, but it is what made us. We should not be ignorant of that foreign country. So, before it's too late for me to tell this story, here are some of my travels in that foreign country.

- Harrogate

- A Good Job and £20 On Tick

- Sugar

- Branston

- Party-line

- Going Up In The World

- Make Do and Mend

- Television

- Dad

- Family Visits Become Holidays

- Maidenhead

- Brotherly?

- Mr & Mrs, and Uncle Harry

- Nipper and Husky

- Mr Lee and Mr Lee

- Eleven-Plus and Onward

- Growing Up

- Sex and Rock’nRoll

- Memory

Chapter 1

Harrogate

There’s not much that I remember about my first four or five years, of course, and some of that is surely mixed with bits I was told or overheard from parents, cousins and others.

I had a pedal car. I used to take all my clothes off, sit on them, and pedal from our house in Kings Road downhill into Harrogate. Presumably just in the summer. Or coast down the long slope to the Majestic Garage (which is no more). Concerned adults and sometimes policemen would bring me back. I remember the doorstep embarrassment of my mother.

I liked to climb on the big red buses, go upstairs and hide under the back seat. The bus would then set off, taking me far afield – to Wakefield once, I was told. I think I kept my clothes on. Police cars brought me back, very good fun. I must have known our address, or was I already known to the police? As a little tyke (not a word you hear much these days).

Around the house I saw some holes against the walls, so I got stones and filled them in. I told Mum and Grandma what I’d done, they laughed and Dad later removed the stones from the drains.

I remember being a source of amusement quite regularly, because I could not say “the door is ajar”, I could only say “the door is a jamjar” and I kept trying but couldn’t get it right. I have no idea what that was all about.

There was a motorbike often parked in the lane behind the house. When not on a bus or naked in my pedal car I could often be found sitting on this motorbike, brmbrming it. There’s a photo of me on it, big grin.

A few houses along, on a corner, lived a doctor and his family. They had an Alsatian dog, which killed their baby in its pram in the garden. I didn’t see this, but I remember it somehow.

Just past this house, across the side road, was a wooded area where I played and made camps and hid. Quite often my parents couldn’t find me. I went back there recently, it’s actually very small.

I remember kneeling on a chair at the kitchen table, watching Mum put a fried egg on top of a pile of mash, my eyes wide, and then the deliciousness of it. Probably the egg of the week. Rationing.

I went to school in my new school uniform. I remember being in a room with a man who was sitting behind a big desk, maybe the headmaster, and my parents sitting there talking to him, presumably about me. What had I done?

Cousin June tells me she came to visit us one day, and went into the dining room where all Grandma’s lodgers were having their dinner. June said, “Ian’s got so many daddies”. They all laughed. For my unmarried mother this probably wasn’t funny.

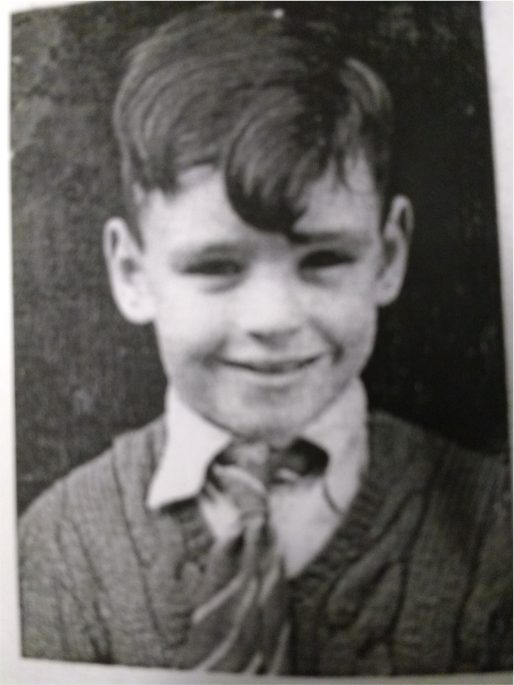

One winter it was very cold and the Stray, a large area of parkland around Harrogate, was deep in snow. They took me for a walk in it, Mummy and this man called Daddy. There’s a photo of me straining against the reins they’re holding; I’m grinning against the brightness and trussed up in clothes, like a mad little dog. This was probably the terrible winter of 1947.

Uncle Harry (no relation) and Auntie Pia (all adults were uncle or auntie) took me for a walk one day. When they brought me back later I was in Uncle Harry’s arms wrapped in newspaper because I’d shat myself. I can remember them all laughing about it on the doorstep. This was when I was very little, I hope. Perhaps they were practising for when they had a child; at least I didn’t put them off having Sandra.

Chapter 2

A Good Job and £20 On Tick

My dad had a good, secure job, a branch-manager in a hardware chain, Timothy Whites & Taylors. But they still had to borrow £20 to buy some basic furniture for their first house. After they had died I found the bill of sale, if it can be called that, a single pencilled sheet torn from a notepad, itemising the furniture to be paid off at 10 bob a week. Nothing more formal than this, no security, done on trust, which seemed to go hand in hand with not having much money, even a man with quite a good job.

When we moved from Harrogate, in 1950, for Dad to become manager of the Maidenhead branch, we lived first in lodgings, rooms in a bungalow on a corner on Pinkneys Green Road. I think an old lady lived there alone; I remember Rick and me being shushed, and us all tip-toeing around, and a garden full of rose beds. I started to go to Alwyn Road Infants School, a short walk away. A family story is that Mum and Dad walked around the narrow, terraced back streets of Maidenhead, near the police station (since re-located), looking for somewhere to buy a house, Dad saying “this is all we can afford”, Mum saying “I’m not living here”. Later they bought a detached house on Allenby Road, within sight of the bungalow we’d been lodging in. Allenby Road was an unmade track at that time, as was Farm Road which also branched off Pinkneys Green Road. Both had houses at the start then further along were still bounded by fields, a quarry and country lanes. I think houses had started to be built along them in the 1920s and '30s, then halted when war broke out.

This was on the edge of town; it wasn’t really in Pinkneys Green which was a mile or more further up the road, a village being absorbed into Maidenhead by post-war house-building. But Pinkneys Green sounded like a ‘good’ address, and did help to locate where Allenby Road was, as there were no postcodes then, not for decades to come.

Everything was budgeted for and planned in advance, by Mum, along the lines of “you’ll need a new school blazer next term”, which meant she was squirrelling away 5 shillings or so each week. Dad kept a pound for himself but handed over the rest of his weekly pay packet, a small brown envelope listing on the outside gross wage, deductions and nett pay, notes and coins on the inside.

While I was still at primary school, Mum announced that she was going to start working, as a hairdresser, which she’d been previously in Harrogate. It was enough of an ongoing disagreement (“my wife’s not going out to work!”) for us little children to realise what was going on. Eventually, Mum started ‘doing ladies’ hair’ in the very small third bedroom upstairs, that we called the box room. This, working but not leaving the house to work, seemed to be acceptable to Dad, no loss of face.

It always seemed to be ‘perms’, and certainly women-only. I asked, and perm meant permanent wave, she told me; but the ladies kept coming back, so it wasn’t permanent I told her! I was a little smart-arse. I remember the smell of peroxide, and the chemistry lab-type bottles and the “don’t you dare touch” warnings. Women then wore hairnets often indoors, whipping them off if they had to answer the door, and headscarves when they went outside, or daft decorative hats for posh events. They never went out uncovered, which in the current concern about muslim women covering themselves we’ve forgotten. It was about a woman’s sense of decency and propriety rather than religion.

Men wore them too, hats not headscarves. Dad wore a trilby for going to work. A solicitor or a bank manager would have worn a bowler. The porter at Dad’s shop wore a cloth cap. All these signals of small difference, showing where everyone stood in the social order, seemed so important. A racy, cheeky way for women to wear a headscarf was to knot it on the chin; convention observed, with a bit of defiance.

To special events, women wore gloves, usually white and thin, not very warm; men's hands didn't get cold so they didn't have to wear gloves when dressed up.

Mum and Dad drove to Soho in London to buy a hair-drier, a huge black helmet thing on a heavy stand. Mum must have found out where to buy this (how? - no Google), and scrimped together the money for it, then badgered Dad into the drive to Soho (“never again”, he said). A 25 mile journey, but no M4 then, into Slough one end and out the other and so on through all the towns and villages that were becoming the indistinguishable outskirts of London. There were no parking restrictions in those days, no yellow lines. So at least when they pulled up outside the shop they could just park on the side of the narrow city-centre street, in Soho in central London – unbelievable now.

Then she bought another hair-drier, silver this time. Another into-the-lions-den drive to Soho. I think her earnings paid for much that we did later, such as horse-riding, and helped her feel she could make decisions where Dad so often feared to take a risk or venture forth. They were very different characters; she seemed the stronger one, more determined and ambitious, but there was still the convention of wives deferring to husbands, or at least pretending to; I don’t remember her ever openly defying Dad.

A common female ailment was ‘nerves’; if a woman looked unwell, or unusually pale or quiet, or hadn’t been seen for a while, she’d be said to be “suffering from nerves”, and heads would be nodded in silent understanding, whispered conversations in the box room as hair was done and local female health was tutted over. The word 'pregnant' was never uttered, always 'expecting', like I was expecting a nice Christmas present.

The hairdressing affected Mum’s hands, the peroxide I suppose, but she carried on for years. By the time I was well into my teens she was doing far less, and I cannot remember what happened to the hair-driers. By that time I was having girlfriends to stay overnight, and sneaking into the little box room at night where they slept, the hair-driers had gone.

There’s not much to say about Saxon, sadly. It would have been Mum’s idea to get a puppy, “for the boys”. But my parents were not really doggy people. He was never allowed in the house, slept in the garage even in the coldest weather; I remember one winter evening Mum putting an old coat over him which, of course, did not stay on. Dad cleared up his shit in the garden, and generally took little notice of him. When we first got him, Mum asked me what we should call him. I said “Chucky” and she said no, later thought of Saxon which suited his colouring. Rick and I would have played with him in the garden, and we took him on occasional Sunday picnics in the Thicket, where he was tied to the bumper of the car. These outings stopped when rabbits on the Thicket got myxamatosis; the clearing where we used to park is now under M4-Henley link road, bastards.

Maidenhead Thicket seemed huge to me, dense woodland, clearings (secret clearings, of course), many winding paths so easy to get lost on. Robin Hood, adventure! I remember planning to run away and live in the woods, and looked in my wardrobe but couldn’t decide which jerseys, trousers etc to take with me, so forgot about it and went out to play. But years later I did adventure in the woods, on ponies, with Rick.

Timothy Whites & Taylors, hardware chain and chemists, is no more, nor is my Dad. Mum died first, suddenly. Allenby Road now seems to me just one more road in a suburb of new roads dense with new/old houses on the west of Maidenhead. Alwyn Road Infants School, where a little girl offered to show me hers if I showed her mine, was re-developed into posh flats long ago.

My parents would have received a weekly family allowance of 5 bob (shillings that is, now 25 pee after decimalisation which was way off in the future) for their second-born child (Rick); there was also a new maternity benefit, unemployment pay for six months if a worker lost his job, sick pay and the new NHS of course. These forms of social support and security were brought in as the post-war Labour government started to implement the 1942 Beveridge report which planned a revolutionary new welfare system for Britain, to create a fairer society. Old age pensions had existed for longer. But I remember no talk of ‘benefits’ or a ‘benefits-culture’, and the insecurities that my parents grew up with pre-war were slow to slip out of mind; thrift and caution remained the watchwords of many families in the 1950s; post-war they were slow to lose the mindset of the 1920s and '30s.

Chapter 3

Sugar

Visiting Marlow, not far from Maidenhead and also on the Thames, a very pretty village, olde worlde, we went into a tea-shop. As a special treat for this outing, we had tea-cakes with butter to be put on them, in a separate dish. The butter was in fine curls, and it had white sugar squashed into it. I remember the delicious crunch of something sweet; not much was sweet in those days, and sugar was rationed. Puddings were stodgy and heavy rather than sweet, tapioca (frog spawn, I called it), custard, creamed rice. The waitress delivered the bowl of sugary butter-curls to our table with a flourish, and as a little boy I loved the rare luxury of it.

Most things were rationed when I was young in the early 1950s, so this was a special treat. We had won the war and ships were no longer being torpedoed in an effort to starve Britain into submission, but we still had next to no food or anything else, except very bad weather. Which is puzzling. Britain sent food to Germany, which was also devastated by the war, and for decades we were paying off a war-debt to the USA, while Germany and the countries it invaded received generous Marshal Aid funding (not loans) from USA. That’s why we had rationing for nearly 10 more years after the war-time rationing of 1939-1945; I don’t remember anyone exclaiming about the injustice of this indebtedness, then or now. I was quite hungry. We all were.

Why were we in Marlow? We went out for special treats and sight-seeing quite rarely. I think there must have been a relative visiting, itself a rare event. Maybe it was Auntie Helen, my mum’s older sister, who did visit us in Maidenhead several times when I was young, when she was between husbands. One time she insisted on buying me and my brother a scooter, the type you push along with one foot. We didn’t want it, we wanted bikes. I got a bike when I was 10.

Another time we went out for a special treat when I was about 14, a restaurant above a pub in Maidenhead on the road towards the river bridge. Quite a group of us, but I cannot remember the occasion, probably another relative visiting. Getting into the party mood, I said we should have some wine. Dad looked displeased, slumped down in his seat, and asked for a bottle of wine. The waiter didn’t ask what wine, just brought us a bottle of Mateus Rosé, not only the house wine but the only wine in the house. Those bulbous Mateus Rosé bottles were coveted (certainly more than the wine inside them) because people took them away to weave raffia around and make table-lamps.

Like garlic, pasta, olive oil, aubergines and a lot of other avant garde vegetables, there was very little wine about when I was growing up, until I was a teenager and we all had Lambrusco inflicted on us. I think no clove of garlic ever crossed the threshold of 57 Allenby Road, Maidenhead. I still have relatives, only a few years older than me, who describe Greek food with a shudder as being “greasy”. It’s olive oil, for christ’s sake! They’d prefer lard. However I did carry on liking a good lardycake (not sure if these still exist; I haven’t stumbled across one for quite a while). What was foreign and exotic and daring to our parents has become commonplace fare, and what was normal everyday grub to them seems a bit basic, stodgy, uninspiring today. However, the purpose of food was fuel, not inspiration or delight.

Somehow rationing kept me healthy, though, and I’ve heard that it made for a very healthy diet (except, you might die of culinary boredom). The bread we ate was white sliced, and we ate a lot of it. My job was to butter half a loaf and lay the diagonal slices on a plate in the centre of the table, for High Tea; this meant you got a thin slice of ham on your plate, with a bit of lettuce and tomato, to be followed by jam on as many bits of the sliced bread from the centre of the table as you wanted, all with a cup of milky tea. Yum. I think this was what happened on Sundays after we’d had a big lunch; during the week we had a cooked dinner after Dad got home at about 6.30 or 7.

Laying the table was one of my jobs, putting out side-plates, getting the cutlery and arranging it properly. This for every meal; it's probably only bothered with now in most families when guests are expected in the house. Were we having fish? - get the fish-knives and forks. Fish-knives seem to have become extinct now, like most of the bloody fish in the sea are becoming.

Everyone had a wireless, The BBC broadcasts were our main source of news, coming into our house in plummy voices better than ours. Broadsheet newspapers were not for us; if Dad had taken a Times into work it would have been thought pretentious, but a tabloid like the Daily Mirror unremarkable.

During the Sunday lunch we’d listen to the wireless (a big plug-in set, no transistors then). I remember listening to Round the Horn and being surprised my parents were OK with all the innuendo which I eventually grasped – Much Binding in the Marsh, etc, and all Kenneth Williams’ campness. The Goon Show was also on sometimes, and I never did get the appeal or humour of it; just a bunch of posh blokes speaking in silly voices and thinking themselves hilarious.

‘Wireless’ was one of things that puzzled me as a child. Why was it called a wireless, when there was wire plugging it into the wall? When I asked, my parents just laughed. Actually, I don’t think they really knew how the sounds got into the wireless, except that it didn’t involve wires. The wirelesses were bulky brown things, sometimes set into big bits of furniture called radiograms. The term radio wasnt really used until I was older and they had transistors and were smaller.

When either of us kids were ill, we’d be tucked up in bed and given a bowl of ‘bread and milk’, which was white bread torn up and soaked in warm milk, with a lot of white sugar on top. Probably what they’d been given as children. Basically just getting calories in. Poverty-medicine, from times when so much ill-health was rooted in chronic malnutrition.

Many decades later, I think it was when I had turned 50, it occurred to me that my mother’s older brother George was probably still alive and I decided to visit him and Aunt Marie. I was having one of my periodic find-my-family phases (about which there is quite another story). I cannot remember where I found their address, but I did and wrote to them, hired a car and went to visit. We sat down in their dining room to the exact same High Tea as in childhood, a thin slice of watery ham, bit of lettuce and tomato, sliced bread and jam, cup of tea. This reminded me of being vegetarian in the ‘60s and through to the ‘90s; you’d tell a waitress you were vegetarian and there’d be a look of either scorn or panic, and you’d be offered a sparse salad with cheese grated on top, or an omelette. Actually, it seems not much different in Yorkshire nowadays when I visit my brother, or maybe it’s just the places he frequents.

Mum spoke about Uncle George a few times when I was young, he was “bookish” and "clever"; at the time I heard this as a younger sister’s awe of her big brother, but later I found out that he was indeed clever. I don’t remember meeting him as a child; they lived in Manchester and I got the impression there was a frostiness between Mum and/or Grandma and Marie (Maari, it was pronounced) who he married. When I went to meet them all those years later he chatted about the family. I knew from odd things Mum had said that their younger brother Jack had been killed in the war, in a tank battle in North Africa; this apparently broke Grandma’s health. Uncle Jack’s memorial was, still is, on Harrogate Stray, which we visited sometimes. George told me that he couldn’t serve in the war because he’d lost his rifle finger in a building site accident; I wondered how he felt about that, tied up with losing his younger brother in combat.

He reminisced about where they had lived in Scotland, and being sweet on the vicar’s daughter, “but…” (as if, unspoken, the social divide was too great). He said when his parents, my grandparents, moved down from Scotland (in search of work?) before the war they went to Hull first, where one of his jobs was to go to the library every Saturday to look in the local newspaper for jobs for his father; I’d understood the family was poor, but they couldn’t afford a weekly paper? On marriage and other certificates I’d seen his father listed as Stonemason, then as Gardener, which sounds like he did whatever manual job he could get, and in those pre-war years of mass unemployment almost any job would do. Grandad Ross died before the war; I found one of the last places he, and they, had lived, a gatehouse cottage on a large country estate beside a road out of Harrogate; probably each time it was not only a job, but a job with accommodation they needed.

I relished hearing these snippets of his early life, more than I‘d heard from my parents, and wish I’d talked to Uncle George over the years, before I caught up within when he was a very old man. Mum mentioned him from time to time, but we never visited or met.

This was the background to ‘feeding the family’, the importance of it, the main parental duty. The tradition in our house, and generally in our circle I think, was for a proper cooked breakfast before setting out for the day, a cooked lunch, then a smaller dinner in the evening. At primary school I used to cycle home for lunch, and was expected to be there for lunch even in the holidays; the regularity of mealtimes was part of the fabric of family life. For years Dad used to come home for lunch; maybe the lunch-time hour was a bit short for this, because by the time I was helping him in the shop he and I went to a cafe in town where we had a proper three-course lunch. I remember the place, on Queen Street, being full of other shopworkers having a proper cooked lunch.

I also remember Rick as little boy, three and a half years younger than me, sitting at the lunch table with his mouth full refusing to chew, and Mum and Dad trying to hurry him along. Which seems to have heralded much of what was to come with Rick, refusing to do what was expected of him.

But "clear your plate!" had to do with our parents' experience of wartime and post-war rationing, the necessity not to waste food. Also, manners, which were a big deal in the 1950s (not much mentioned today), a social, almost a moral, code; even the smallest things could be 'bad manners' - a judgment which once uttered was unquestionable, a failure of 'breeding'. Leaving the dinner table before others had finished was bad manners; placing knife and fork neatly together on the emptied plate was good manners, and "may I leave the table?" I remember Mum would sometimes ask "have you had a sufficiency?" which seems ridiculous now, but was all about being 'well-to-do', what she thought an upper class woman might say at the end of a meal.

"Don't lose your temper" was a common reproach, not just in our house. This was about manners too, as was "don't let yourself down" - in terms of the standards you should maintain for yourself.

To an extent, it was a world of pretence, betterment and euphemism; your bottom was your 'btm'; someone was not fat or had a beer belly, they had a 'bit of corporation'; one never farted, one 'let off'.

It would have been thought very rude for anyone, especially an adult, to drink straight from a bottle as is common today; even in the most basic pubs this was not done; to do so in company, would have been taken as insulting.

Of course what I remember from the late 1940s and the 1950s are fragments, without much context. Writers who lived through the war have revealed a lot more what it was like then, what life was like for people like my parents and others higher up the social scale. Writers such as Mary Wesley who only became an author when she was 70 so was writing in recollection of those times. Others like Marghanita Laski were writing and publishing during those years.

To go shopping you needed your ration book, stating (limiting) what you could buy. Until I was seven everyone also had to have an ID card (Mum had somehow fiddled things so that mine had my stepfather's surname rather than Doucet as on my birth certificate, I realised much later). As well as food, fuel and clothing, furniture was rationed and later still in short supply; ‘utility’ furniture (a basic, standard design) was almost all you could get. Paper was in short supply too; the government dictated paper quality, type sizes and margins, print length etc during the war years. Paperbacks printed in the 1940s and 50s are generally of poor quality and binding, narrow margins and gutters.

Rationing was not the whole story. There were differing views on the post-war Labour government’s welfare policies, including creation of the NHS, but overall there was a general dismay at the state of Britain, victorious but financially ruined by the war and struggling to feed its people. Some saw this as part of a long decline, and there was a surge in emigration to countries like Canada and Australia which offered more hope, prosperity, space, new-ness. In The Far Country there’s an interesting lengthy account of postwar Britain. One of the book’s characters, Jane Dorman, who had emigrated after marrying an Australian at the end of the First World War, receives letters from an aunt in Britain and reflects that:

“there was a menace in all the news from England now… In all her life, and it had been a hard life at times, she had never been short of [meat] … It was the same with coal… she had never had to think of economizing with fuel”.

The aunt, once well-off, then dies in poverty, malnourished, and Dr Morton reflects,

“The standard of living had slipped imperceptibly in England as year succeeded year, as war succeeded war…. In each year of peace the food had got shorter and shorter, more and more expensive… He was now living on a lower scale than in the wartime years; the decline had gone on steadily… Where would it all end, and what lay ahead for the young people of today in England?”

In the book, an official who cut off the aunt’s electricity (reluctantly, for non-payment) says:

“It’s getting worse each year. Sometimes one feels the only thing to do is to break out and get away while you’re still young enough… Canada, perhaps, or in South Africa.”

The main character, Jennifer, works at the Ministry of Pensions, and the author (Nevil Shute) gives a lengthy, balanced discussion between staff there of the pros and cons of rationing, other policies, and emigration, in this context:

“That was a time of strain and gloom in England, with the bad news of the war in Korea superimposed upon the increasing shortages of food and fuel and the prospect of heavy increases in taxation to pay for rearmament. In the week following Jennifer’s return to work the meat ration was cut again... only sufficient for one meagre meal of meat a week.”

In Derek Beaven’s Acts of Mutiny, set in the late 1950s, the extent of migration (driven by poverty and homelessness, and officially sanctioned) and attitudes to it are depicted; on the ship heading for Australia the “£10 migrants” are shut off from other passengers in ‘steerage’ behind a metal wall, and referred to as “white niggers”. The ship, also carrying a secret cargo for the UK’s nuclear testing based in Australia, is a “floating showcase” of English social distinctions, snobbery and hypocrisy; while furtive affairs are had, a couple who openly fall in love are shunned. The non-steerage passengers are colonials seeking retirement anywhere but an England ruined by victory, or young men pursuing better careers:

“...he would build a new life for himself, a better life than the grubby, rainy, pompous, clapped-out little island of his birth could offer”.

The grim post-war situation is also conveyed in a few films of the time, which started the genre of kitchen sink drama, realistic portrayals of everyday working life, which I watched in later years: It Always Rains On Sunday (1947), Look Back in Anger (1959), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960). I have found descriptions of grey, difficult years, the small everyday circumstances of individual lives, more vividly in novels and films than in the generalisations of social history; there are exceptions such as Maureen Waller's London 1945 detailing ordinary life at that critical time when the war ended:

"grimy, grey drabness. Buildings black with soot... Mean terraces... After five years of war, the people looked tired and worn... all pervasive smell. It was of coal smoke in the damp chill... Dust so acrid you could taste it in the mouth."

My parents brought us up in those years, but never talked about what it was like for them, and I never asked before they died, too busy with my own life in better times. Did it affect me, growing up in that atmosphere of the unspoken, of secrets, of grim constraint - and (I am still finding out) so many relatives denied? If they had not closed off the past, it would have helped me understand why they were the way they were, and appreciate much sooner how much they were doing for us. Instead, late in the day I have had to do that searching out work, and can only say posthumous thank yous.

Nevil Shute was one of the authors my parents might have had on the lounge bookshelf. He was born more than a decade before them, so his books would have been around as they grew up, and were popular. I never read them, wouldn’t have done because they were of my parents’ generation or earlier. But I find them interesting now, revealing about life then. Some of stories reveal the small details of life in war-time Britain, young men and women growing up, falling in love, facing separation, and death or injury: Requiem for a Wren, Pastoral, Landfall, The Chequer Board. Others portray individuals living through war elsewhere, and going on to make their post-war lives outside Britain: A Town Like Alice, and Beyond The Black Stump. Almost all the main characters are young, and he creates strong female characters.

Chapter 4

Branston

Back then it seemed a bit posher if your house had a name. Our address, 57 Allenby Road, Pinkneys Green, Maidenhead was good enough to get our post delivered, but a little signboard declared that it was ‘Branston’ that my parents were buying, when I was 5 years old, in 1950.

Why not ‘Ketchup’? I don’t remember anyone ever questioning or seeming slightly embarrassed that our house had the same name as Branston Pickle. When my mother and father wrote letters, they were addressed as being sent from Branston, 57 Allenby Road. This was the proper thing to do, and it was important then to conduct oneself in a proper way in the many small acts of everyday life.

In those early years in Maidenhead there national events written about exuberantly in the newspapers and by commentators since, the Festival of Britain in 1951 - "a tonic for the nation, a spectacular cultural event to raise the spirits of a country still in the grasp of austerity and rationing, and undergoing severe social and economic reform". And Queen Elizabeth's coronation in 1953. It seems there were street parties across the nation, but not in Allenby Road, nope, too common, that was for working class places.

Branston was a detached brick two-storey house with bungalows on either side. The front door was set back a little behind an arch, which seemed rather grand. There was a lounge with a bay window (another desirable feature) at the front, behind it the dining room and the kitchen. The kitchen was small and simple, with just space for a sink and drainer beside the back door and a cooker on the back wall; so different in space, facilities, and just comfortableness, from almost any kitchen you’d find nowadays in this country. You wouldn’t want to linger in the Branston kitchen. There was no heating, little light and no nice outlook; the only window looked onto the neighbour’s fence and later onto our new garage wall. Today it seems normal for a kitchen to have a pleasant outlook if possible, and there’s an expectation that it will be a pleasant room to spend time in. But in the 1950s kitchens were just functional, and not to be lingered in.

Upstairs there were two bedrooms, what was called a box room, and a small bathroom. Mum and Dad had the front, bay-windowed bedroom and we boys had the back bedroom; this had a cupboard within which was the immersion tank; they thought this would make our bedroom a little warmer (it didn’t, but it was a nice idea). Every morning, first thing, one of them would come into our bedroom to switch on the immersion heater so there was hot water for washing.

The bathroom was above the kitchen, the same size (small) and the same just-enough functionality: a bath, basin and toilet squeezed together; another room not to linger in. ‘Ensuite’ was light years ahead in the future, a concept unheard of – what, a bog just beside your bedroom? ugh, why? For my mother and father whose parents came from a time when the bog was usually at the bottom of the garden, having the lavatory inside the house at all was a sign of living in modern times (and ensuite is a strange adoption in English usage: it means ‘following’ or ‘next’ in French, like puis, so it is next in a temporal sense not a spatial, next-to-the-bedroom sense. But who cares?).

Our bathroom may have been small, just room enough for one person to turn around in. But we were in the modern majority in having a bathroom at all - in 1967, by the time I had grown up and long left home, a quarter of homes in England and Wales still lacked a bath or shower, an indoor WC, a sink and hot and cold water taps.

I realise now that my parents were ambitious, and confident, in buying Branston. Not only was it the only two-story detached house in a row of bungalows, it was quite modern, built in the 1930s on fields along a farm-track during a short-lived house-building boom. It had pretensions, this house, in what it presented to the world - the arch above the recessed front door, bay windows at the front, the elaborate mantle-piece in the lounge (where visitors would be entertained) – and in what it lacked: no kitchen with a range as the centre of the home. It was decidedly not a working class house, where a family gathered in the kitchen which however crowded, dingy or messy would be the warmest and homeliest part of the house. Instead, Branston had a small bare kitchen, its gathering places designed to be the dining room and the lounge, and thus less homely in my opinion, especially in the days of barely-heated houses. There were fireplaces in the four main rooms, but keeping them all fed with coal and cleaned would have been a major job, and no space for a servant here; expensive too. We never had fires lit in the two bedrooms. So for all its pretensions, Branston was probably quite a hard house to live in.

No washing at the kitchen sink for us, we had a bathroom basin; no tin baths in the kitchen with water heated on the range, we had a proper bath (in an unheated bathroom – you didn’t wallow, you shivered and scrubbed quickly). And no shower, or mention of ever getting one. I don't think we knew of anyone who had a shower, though we probably knew that Americans had them.

For years there were only the coal fires, in the lounge (lit at weekends) and the dining room (lit in the winter evenings). The house was cold; there was ice on the inside of windows on winter mornings. We’d often get dressed under the blankets and the candlewick bedspread. Blankets not duvets; you could pile more and more blankets on your bed but there was a point of no return, where the sheer damp weight seemed to start making you colder. At this time, there were jet engines, sputniks flying through space, nuclear weapons, but our houses still relied on lumps of coal in an open grate for heating. For gods sake. The same as houses in this country had been heated for hundreds of years. Never mind that 2,000 years ago the Romans here had hypocausts, heating the floors of their villas. In keeping-warm terms we were still back in the Dark Ages.

Most of the heat went up the chimney. To get the fire roaring, Dad used to hold a sheet of newspaper over the top half of the chimney, and whip it away just as the heat started to burn the paper. I think this was a common trick, and somehow the man’s job; I never saw Mum doing this. You were only warm if you were close to the fire, chairs were arranged around the fireplace (until we got a telly, which changed everything); armchairs had not only arms but sidepieces and high backs to shield you from drafts and the chill in the rest of the room. But it was nice to see the flames, somehow cheering even if you still felt a bit chilly. And the fire was useful for toast, made by putting a slice of bread on a toasting fork and holding it in front of the coals, then turning it to do the other side. There were no modern electrical toasters in those days, at least not for us. Toasting forks seem to have gone the way of fish knives.

We never burnt logs, only coal. Log fires would have been regarded as a real sign of poverty, a sort of peasant-poverty. Nowadays, people in cities and suburbs with their centrally heated houses have log fires for effect, not essential warmth. My parents would have laughed at this, the height of wastefulness.

Some years later, when storage heaters became popular, a couple of these were installed downstairs. They were better, but hardly a great technological leap forward in home heating, basically just heating stones to give off their heat slowly over the hours, which people have been doing since the dawn of time (and fire). The only difference was that the stones (bricks) were in a metal box, and heated by night-time electricity which was cheaper. They were bulky and expensive to buy (we may have got them on ‘hire purchase’, popular then). The modern concept of insulation hadn’t arrived by the late ‘60s when I was leaving home, and I’m pretty sure the house never had any roof insulation, certainly no double glazing.

But it wasn’t a cold house emotionally. We were kissed goodnight, and well looked after. Christmas was made much of; only one present each but a long sock full of goodies, chocolate, an orange, and a few other things. For a year or two on Christmas Eve they put a small fold-out card table at the bottom of our beds with a couple of mince pies and a drink for Father Christmas when he came down the chimney; after we’d gone to sleep they removed the mince pies, left a few crumbs and guzzled some of the juice. One year I tied a length of wool from my toe to the door-handle so I’d wake up when they came in with our presents. But I didn’t wake up because the door opened inwards.

The Christmas tree was placed in the lounge bay window so it could also be seen from outside; we decorated it with lights (Dad going “drat” as he removed each bulb to find the dud one). Rick and I licked and looped together coloured adhesive strips to make chains we hung on the tree and in the hall. As decorations we also used offcuts of the gold, silver and green foil stamped on the top of milk bottles at the dairy further up Allenby Road. I’d often be sent to buy an extra pint, gold top with all its cream on special occasions, usually silver top, never green top which would have signalled that we were having to watch every penny.

When I was older, 10 or 11, I helped the milkman on his round, running from the electric buggy to doorsteps with the orders he called out, and getting a pint of gold top for my efforts (no worries about cholesterol then; fatty foods were good, energy and warmth). By the 1990s the dairy had gone, too small to be economic and worth more as a demolition site for posh flats.

Mum did get fed up with the very basic kitchen. In the late ‘50s she persuaded Dad to get builders in to make it bigger by knocking the back wall into the outside toilet and coal shed, with a new wide window looking down the garden. Then there was room for a fridge; before, everything was kept in the cupboard under the stairs, which had a small mesh grill to the outside to keep it cool (bloody freezing, actually).

They didn’t get a washing machine until after I had left home; everything was washed by hand (no laundrette nearby, or did they exist then?).

There was a long garden. That’s one of the better things about these houses, they were not built on the squitty little plots that modern houses have. Behind the house was a lawn, shed to one side, hedge to the other, and lower down were large vegetable beds. Mum and Dad built a rockery and pergola between the two, and in the early years planted and grew quite a lot of vegetables there - a carry-over of the war-time habit of families growing food wherever possible to supplement rationing. At the end was a hedge, with a gap where you could look down into an abandoned chalk quarry; it looked very, scarily deep to us. Beyond that were fields and woodland, Maidenhead Thicket. Quite a bit later, when she had got some spare time (how?), Mum laboured away to dig out and concrete a pond to one side; not sure why, it wasn’t deep enough to splash about in much, and it was under trees so was usually green and leafy. I remember Dad telling her she’d have to dig a bit deeper in the middle and put an old milk crate in this drain-away hole, so the pond could be drained later. Isn’t this interesting?

He showed her how to mix the concrete (no small electric cement mixers then; just pile up the sand, stones and cement, mix, add water, turn it over and over). He knew how to do these things, he just didn’t do them very often. Ten or more years later there was still a pile of left-over sand in a corner by the shed; I have a photo of my toddler-age daughter playing in it, sea-side bucket and spade in hand, and big sunglasses.

At first they got a decorator in, and I remember the lower half of the walls in the hall being painted brown, the upper half a paler shade; the brown paint was textured and oiled somehow so the colour varied (deliberately, I cannot recall the name for this technique, but it was quite traditional at the time). Later, they did their own decorating, wall-papering etc, with lighter colours. They also had a modernising phase, where the banisters were boxed in with hardboard on both sides, painted white, and the rather fine frame-and-panel inner doors (solid wood, much prized today) were also given a smooth featureless covering of white hardboard.

Beside the house was a fence with a snicket gate (snicket isnt a word you hear much these days). At the momentous time we acquired a car, they had the fence replaced by a garage, filling the space between the house and neighbouring fence. I remember them discussing whether the garage walls should be double thickness, so that later another storey could be built on top, but this would have cost a lot more and couldn’t be afforded. There were other improvements. One day I came home from infants school to see a man on a ladder throwing stones at cement smeared on the brick walls. Pebbledashing was one of the trends then for improving houses, but all it did was change their appearance a bit. The short drive was tarmac’d, by a work-gang who turned up with a story about cheap tar left over from another job. This was a common con; within a few years the tarmac became loose blackish gravel. Not enough ‘left over’ tar to hold it together.

Mum nagged Dad into putting bookshelves in an alcove of the lounge, just a couple of shelves up to waist height, but he moaned about having to spend his Sunday doing this. Neither of them read much, but over the years Mum accumulated Readers Digest versions of popular books, and probably some classics. I never read any of them, even when I was old enough; they were boring, old-fashioned, grown-up books.

These and other changes to the house marked Mum and Dad’s gradual achievement of financial stability, after they’d started by buying £20 worth of secondhand furniture to move in with.

Cold houses were normal in those days, and not just because no-one had thought about heating or insulation (in fact, house construction had gone backwards in that respect - thatched roofs were much better insulation than tiles or slate, and nothing had replaced that natural insulation effect). Double glazing? - nope. As the war drew to a close, 1945 started with:

"...the coldest January for 50 years. There were sheets of ice in the Straits of Dover and in London Big Ben froze. Children, wrapped in mufflers and mittens, returned to school to find the ink in the pots frozen. ... On the doorstep, milk froze in the bottles, which did burst. Thousands were suffering from burst water pipes... seriously hindered progress on the repair of war-damaged houses... Trains, which were unheated... [and left people] frozen to the marrow."

– Maureen Waller, London 1945

This continued in the next couple of years, and coal was in short supply (many miners had been taken into the military):

"The freeze started in December 1946, when fuel supplies were already running low, and as temperatures plummeted coal stocks dwindled to almost nothing. [This] ... inspired a fashion for electric fires. Consequently, the Electric became endangered too.... [As a result] Electricity was rationed along with jam and soap and margarine. Factories across the country were forced to close, television was off air, broadcasts on the radio were reduced, also the size and thickness of the newspapers... War was over but life was still a battle with rations even meaner than before... Vegetables had to be dug up with pneumatic drills. Sheep and cattle froze to death."

– Patricia Wastvedt, The German Boy

And similarly with 1948, reputed to be the coldest winter of all. That's when the photo of toddler me was taken, wrapped up and on 'walking reins' (gone out of fashion, good) on a snow-bound Harrogate Stray, Mum and new Daddy smiling behind me.

An English woman married to a German pre-war, and stuck in Germany, returning post-war wrote:

"In England there was so much to learn... I found myself trying to make out just what had happened to my country. England had won the war, the boys were coming home again... and yet it was so very dull... now everyone was simply tired out... the newspapers excelled themselves predicting one catastrophe after another... The coming winter was to be the coldest in living memory; an influenza epidemic of dire proprtions was also on its way... due to a state of near-starvation in Germany, the rations in England could not be kept the same level for much longer."

– Christabel Bielenberg, The Road Home

Len Deighton’s non-fiction book Bomber traces the wartime exploits of an RAF bomber crew (it’s easy to overlook that they are very young men) and then their various individual ways of returning to civilian life post-war, picking up old jobs, finding new careers, resuming young relationships or finding that girlfriends have moved on. But for the different location, these could have been the young adults around when I was a boy in Maidenhead. Nothing was ever said at the time about the recent war-years, so it has taken me half a century to learn about the adult world I was growing up in, who the people were around me and what their lives were like.

Chapter 5

Party-line

Our telephone was on a party-line, the only sort of phone connection you could get back then, years after we’d won the Second World War. I don’t know why. Was Bakelite rationed, or thin copper wire, or were telephone engineers rationed? Bakelite was a brittle, hard kind of plastic that everything was made of (unless made of wood or metal, of course, and even we didn’t have a wooden telephone).

Party-line did not mean that your phone brought you lots of invitations to parties. It meant you shared it with your next door neighbour. It could have been worse, with one phone perched on the garden fence and both us and Mr & Mrs Alexander next door rushing out in all weathers to answer it. No, we neighbours each had a telephone, but connected to the same wire.

This meant there could be a lot of nosey listening into other people’s conversations, and therefore a horror of this in ultra-respectable lower middle class definitely not working class Pinkneys Green. If the phone rang and you picked it up but the call was for the neighbours, or you picked it up to make a call and heard them talking already, you said in deep, bank manager-ish voice “I’m very sorry” and put the phone down quickly. Everyone listened for the click as the other phone was put down, checking that neighbourly proprieties were being observed.

It was expensive to make a phone call, there were no cut-price plans as now, and only one company so no competition. Long distance calls were called trunk calls; they had to be requested through the operator; phone exchanges had banks of operators (always seemed to be women) to make these long distance connections. Companies had smaller versions of the telephone exchange, women who connected your call to whoever in the company you wanted to talk to; what we call direct lines didn’t exist then. Trunk calls were much more expensive and made only in times of some major family event; there was a warning when three minutes had elapsed, to avoid people running up huge bills. I don’t know when this three minute warning was dispensed with, maybe by the time we were all living under a four minute warning, which was quite another thing.

As well as operators to engage with when making a long distance call, there was The Speaking Clock. If you dialled a certain number, a woman's voice told you the time. Why? Did they think we were so poor we didn't have clocks and watches? The voice was actually quite soothing in it's regularity - "at the next stroke the time is... at the next stroke the time is..." I think some people listened to it cos they were lonely, or bored as I was often.

International calls were an ‘almost-never’. Many more letters were written then than now, and it would not have occurred to my parents to make an international phone call; instead, they would have sent an airmail letter - very thin, blue paper which folds and seals on itself to become its own envelope, to save weight as overseas postage was expensive. Barely seen nowadays, but I was still using them to write home to Mum and Dad in the late 1970s (email still 20 years away) while I was living in Greece.

Except for the very rich, there was only one phone line coming into a house, and even ‘extensions’ were rare; we never had a second/extension phone in the house. Of course there were no mobiles, not even dreamed about except in science fiction; Dan Dare had something like a mobile on his wrist, that he used to speak into. Ridiculously far-fetched.

So phone calls were as brief and to the point as possible, not made for a casual chat, let alone anything personal or private. They were made to send or receive important information, and conducted in as near to BBC-English as any of us could manage. My parents spoke as if the telephone company required them to adopt as posh an accent as possible, clipped, very very polite, deferential. The message to convey in your voice was “I am not common, I have High Standards, this is a respectable house.” Even as a boy I winced with embarrassment hearing Mum and Dad speaking on the phone. Once, when we were visiting my cousin June on a housing estate in a suburb of Leeds, the phone rang while only Dad and me were there. He looked a bit panicked, eventually picked up the phone and said in a deep, butler-ish voice, “this is the Dean residence”, to the person phoning June’s second-hand car dealer husband. This became a family-reunion joke for years.

Dad often spoke to strangers as if to 'authority'. One time on a trip to Harrogate, we stayed at a pub in Knaresborough. This must have been before we started staying at cousin June's house on our bi-annual visits to Grandma Ross. In the bar, customers drinking, standing around, he went to the far end of the bar, beckoned the barman over, and said out of the side of his mouth, very discreetly "are you residential?". It sounded so furtive.

Our telephone was in the hall, on the hall-stand. You stood there in the chilly hall and used it when necessary, not for enjoyment. Hall-stands are pieces of furniture invented for this purpose, and probably not nowadays for sale in Ikea. Our hall-stand was narrow and upright, which seems symbolic now I think of it, with a space either side for umbrellas and walking sticks. Telephones then were not private, they were family possessions for family business. The notion of each of us having our own phone and ability to have private conversations - anywhere - as now with mobiles, would have been regarded with alarm and suspicion, underminng of trust within the family. Even years after I'd left home, was married, a child, job and mortgage, we had only one phone in our cottage. So much of a young person's life, even a child's, centring today on their own personal phone would have seemed very odd to my parents, disturbingly secretive, un-anchoring them from the family. I didnt get my own phone (a mobile) until about 2000, and then only needed it for work I was taking on.

I learnt only long after my brother and I had cleared out the house, Dad having just died and Mum several years earlier, that that hall-stand was a precious item of furniture; Grandma had bought it for her large house in Harrogate when she was making a go of having lodgers and then given to Mum when she and Dad made the big move to Maidenhead, as a sort of token of affection and support. Rick and I went through the house like a dose of salts, clearing out and sending anything saleable to the local auction. Even as I was then, thoughtless and worse, had I known I think I would have kept Grandma’s hall-stand. In our family, so little was spoken about family, or feelings, and what really mattered, but our telephone accents were quite impressive.

Life before mobile phones was less stressful, I am convinced. In books set in pre-mobile times, the plotting and narrative are noticeably different. You could be wonderfully out of contact with other people for as long as you liked; another way in which kids today have lost the freedom we had.

Although mobiles have made a huge difference to how we live, and can do marvellous things (that we’ve never needed to do before), they did not suddenly spring into existence fully formed as they are now. I first experienced a mobile phone (to put it quaintly) as something of a surprise, when a girlfriend and I had stripped off for a bit of lunchtime sunbathing in the garden of the office I worked in, in Alton in the 1980s, and stretched out I heard a phone ringing seemingly from a car parked several yards away behind a hedge. Dressed, I went to investigate and met the guy who repaired cars there; he showed me the mobile phone that was in a car he’d just bought. It was huge, the size of a shoebox, and heavier than a brick; you could pick it up but no way would you carry it around with you. He said the military had them, but the batteries ran out in minutes. I was in my late 30s then, recently divorced.

Mobiles were smaller in the 1990s, but all they did was make and take phone calls, and then only from limited locations. When I lived in London briefly, businessmen would crowd outside Bow Road tube (and other tube stations where there was a mobile connection) making their essential business calls before dashing off out of mobile range. Kids didn’t have mobiles then, they were too expensive, and all the things you can do on a mobile now were still undreamt of.

Chapter 6

Going Up In The World

We moved to Maidenhead and then into 57 Allenby Road when I was five. I loved the wide unmade road for playing in, before there was much traffic and what there was moved slowly over the rough surface. There was no pavement. At the top of the road, where it merged messily with Farm Road (also unpaved) and Pinkneys Green Road there was a field with an old black and white carthorse in it. When walking back from the infants school in my uniform, I used to climb into the field, cross it and then climb out again, rather than walking around it more simply on the roads. In those days, even little kids walked to and from school, and were expected to. One birthday I lost the multi-coloured biros I’d been given while climbing in and out of the field, and spent ages looking for them, unsuccessfully.

Beside the field there was an area of allotments. These seemed to fall out of favour in later years of Thatcherite individualism, but in the '50s they continued the wartime and postwar enthusiasm for communal effort and growing your own food as much as possible. Too many were bought up by developers, but those that remained have became popular again.

A little further down the road, just past our house, there was another field in the triangle of land where Twynham Road branched off. With a couple of horses in it. Before I went to secondary school and acquired an uncaring persona about such things, a church (nasty, modern) was built on the carthorse’s field at the top of the road, and two semidetached houses on the triangular field. I hated these losses. And Allenby Road was tarmac’d and kerb’d and pavement’d; no puddles and no longer wild. Bastards. Each house had to pay towards the cost; I remember the figure of £120, and there was much muttering over garden fences, which was about as rebellious as any of the adults was capable of getting.

Dad was no entrepreneur. His job was secure and I’m sure he got salary-rises, but equally sure he never pushed for these, and resisted Mum’s urging to press for more promotion or a new job. Instead, they saved, and planned, everything from a new school blazer next year to building the garage and getting a car. Mum started hairdressing at home, investing in one then two hairdriers. At her urging, they did toy with other ways of getting on. There were a couple of money-making ideas they and other people experimented with in those years, such as Dad going door to door with paraffin (used for small heaters in houses, smelly but popular when there were so few ways to heat a home). Breeding mink in the back garden, to be culled for their fur, was another idea being promoted, and they considered it; perhaps the logistics, or possible problems with the neighbours and council put them off. Or they realised the only people likely to make money out of this were the suppliers of mink and hutches etc. I can see them now having serious talks in the lounge, him working out the figures with pencil and paper, and concluding too much risk, too little reward. He was probably right. They did OK as they were, carefully and gradually.

They had a few ready-made answers to what life might throw at them: “watch the pennies and the pounds will look after themselves”, “never a lender nor a borrower be”, “don’t get above yourself”, “know your place”, “charity begins at home”, “do unto others as you would be done to”, “never volunteer”, “every cloud has a silver lining”, “it’s an ill wind that blows no-one any good”... They had a basically Christian morality which was also a social-conformity ‘keep-your-head-down’ morality, but never spoke of religion and I don’t think we ever went to church; I’m pretty sure there was no bible in the house. We didn’t say prayers.

There were two postal deliveries each day; bills were delivered by post and paid by sending off a cheque, or by visiting suppliers’ offices in town; gas, electricity, coal companies all had local offices in each town at that time. Credit cards and online banking were far into the future; it was a cash economy, with cheques for large, occasional purchases. Mortgage payments were commonly made across a building society or bank counter, rather than by direct debit as now.

Because many people were paid in cash, weekly, they did not have bank accounts so could not pay by cheque. Instead, and to avoid carrying large amounts of cash around, postal orders were commonly used - 'sort-of-cheques' purchased at a local post office (of which there were many more than now); postal orders seem to have almost ceased to exist. They were also used to make bookings for hotels, boarding houses etc, being posted in advance as payment or deposit.

As the area went up in the world (that was the phrase then, and everyone’s aspiration, shared but always unspoken), so did we. We acquired a car. Surely this was driven by Mum’s ambition and what she earnt from doing hairdressing at home, but might have taken longer if my parental innocents had had to venture into the secondhand car business alone. By this time cousin June back in Yorkshire was going out with (married to?) Tony, a secondhand car dealer. He got Mum and Dad an old Vauxhall J-type, three gears, big bench seats front and back, with wings over the front wheels, doors that opened forwards, black as almost all cars were then. This was just about the time when new cars were starting to look like cut-down versions of American cars, full-width bonnets but with the same mechanicals underneath, bright colours, all flash and chrome, and crap, unreliable.

Eventually the Vauxhall got a re-spray, which they weren’t satisfied with, and visited the garage in Slough to complain. On the Bath Road, the straight bit of the A4 through Maidenhead Thicket, they got the Vauxhall up to 80mph on the flickering speedometer (couldn’t do that now, there’s a roundabout in the middle of it). Later on, Mum got a fur coat, a lustrous black fur coat, very full and sweeping. I can’t remember the details, but she must have longed for this for ages, saved and been determined to get it, as showing the sort of people they really were, respectable, not common. I’m not sure that she had many occasions for wearing it, but maybe that wasn’t the point. Being common was something to be avoided, but this was about behaviour rather than poverty. How they might have put it was that you could have standards even if you didn’t have much money. I remember them saying that they didn’t want to be rich (that was a bit ‘vulgar’, or to want it was), no, they wanted to be ‘comfortable’.

At that time, a woman called Lady Docker was in the news often, in the context of some scandal like being drunk in public or flaunting an affair; I remember them turning their noses up at this behaviour, she may be rich but she was vulgar.

People would talk of "Going up to Town" - that odd, English reverse-snobbery way of referring to London, a city - "to see a Show". Those were words used by people 'better' than us, and doing that was not for the likes of us.

The fear, overriding everything, unspoken but always in the air, was of unemployment and slipping into poverty; my parents’ generation had been brought up in this atmosphere, and the new post-war welfare system was slow to change these attitudes. This was the context within which everyone like us lived, our lives being the effort to rise above this. One accident at work, a business going bust, a chronic illness, could shatter the family’s survival system. Or it could be ‘character’ - alcoholism, or ‘playing away’ – the impact of sexual infidelity being on the family’s economics as well as social respectability. I remember so much of this from my primary school years, but it lived on, this fear our families all shared. When I was at secondary school, around A levels and me a kind of studious tearaway, I remember a friend telling me his dad had stood him against the wall and told him this (exams, grammar school) was his one chance to make something of himself. His family lived in a new house on a new housing estate, his father’s hard-won achievement and that family’s going up in the world. Those were the parental frames of reference then, which I scorned and rebelled against, but somehow my parents or the times infused me with a work-ethic and intolerance of laziness, without me realising it.

Character was a common frame of reference, and judgement. Laziness was regarded as a sin. Words you'd here then, seldom now, were 'malingering', 'dilatory', 'work-shy'.

Other moralistic phrases of the time were 'everything in moderation', and 'stiff upper lip' - it being as important to keep your emotions in check as to keep careful control of your financial outgoings. Mum and Dad would not have used those two phrases, but if they'd heard someone with higher social standing than them uttering those words, they'd have agreed.

Cycling to primary school I would pass the council house where a schoolfriend lived, on a corner of the new council estate which came after the ‘prefabs’ built quickly straight after the war. Roger’s family went up in the world too, moving from the crowded, semidetached council house to a much bigger, detached house in a ‘better’ area on, I think, Belmont Road, or near there. The measure of his success, status-social climbing in those days, was Roger’s dad becoming president of a local club (yacht club?). As skulking-about teenagers Roger and I went to some social event there, and I saw a portly man in a blue double-breasted blazer and slacks puffing a cigar as he gazed presidentially over the proceedings from a balcony; I laughed at the pose, the pomposity. Roger said, “don’t, he’ll see you, that’s my dad”. So, not bold independent Roger after all.

Only much later have I understood it, that they grew up in the 1920s and 30s when the absence of fathers, brothers and uncles lost in the First World War was still keenly felt, and other family members lost in the TB outbreak that followed that war. When they were young men and women meant to be making their way in the world there was the economic depression of the 1920s and continuing unemployment of the 1930s. Then there was wartime rationing, shortages and an uncertain future, contimuing into the 1950s. Our family life was shaped by this.

With most men away fighting the war, it was women at home who had to deal with the war-time privations, and like my mother they carried the habits of ‘make do and mend’ into their post-war lives where shortages and rationing continued for another 10 years.

Their thriftiness rubbed off on me. That’s why I never started smoking. What a waste of my meagre pocket money. As a teenager there was no chance I’d be able to buy a record player, or get one at Christmas, then afford LPs. So eventually I got a little tape recorder, much more sensible, and recorded from crackly Radio Luxembourg. But later on this sensible attitude faded, and the abandon and wastefulness of my young adult years sat badly with who my parents were. Badly and, on reflection, sadly. Their work brought us freedom, escape from their world. They died before I had it in me to show my thankfulness.

The Vauxhall J-type, the bigger kitchen, the garage and later the fur coat marked a big shift in their fortunes, from the time soon after we arrived in Maidenhead when they both had all their teeth taken out, to avoid the risk of future dentistry costs; this was common practice at the time. Barely in their 40s, and then for the rest of their lives a glass each side of the bed for the dentures, and mumbling to us kids in the morning until they’d put them back in. Today, still with my own gnashers though a bit off-colour and battered after 79 years, I find this shocking.

It was a priggish, prejudiced world too, my parents’ world, and quick to judge. Across the road from us and a few houses down, a single woman and her son, about my age, moved in. She was much spoken about but seldom spoken to. Her husband might have been killed in the war, or in Palestine or Korea or elsewhere that Britain continued to be involved militarily after 1945. But she was a single woman with a child, and was always referred to as “the divorcée”, without any knowledge that this was the case, I think. Never spoken of by her name, or befriended, that I saw. Pronounced “divorcy”, at which I would smirk, since I was doing French at school by that time.

I’d forgotten, until reminded by something I read recently, the awe and admiration with which the USA was regarded in the 1950s. The later anti-war, anti-Vietnam, anti-nuclear-arms-race subculture had obscured that in my memory, but in the 194os and ‘50s America was regarded as a marvel of technology, can-do, sophistication and Progress. The phrase "it's not rocket science!" became a common exclamation, meaning something was not really difficult, because to us inventing rockets to reach outer space - rocket science - seemed the ultimate scientific achievement.

What reminded me of this was Nevil Shute’s Beyond the Black Stump where a young Australian woman marvels at the bright new world of things-American in magazines, then visits with her American boyfriend; this comes across as Shute’s own admiration of the ‘way forward’, a better future exemplified by America. Nevil Shute was a public school-educated Englishman, who after war service despaired like others of a postwar Britain stuck in poverty and debt. Similarly, in Ellen Feldman’s The Boy Who Loved Anne Frank the main character escapes post-war Europe to 'make good’ in America, and later takes pride in his children also thriving there, the USA as the place of safety and the ‘good life’. In the post-war years, living in war-torn, exhausted and impoverished Europe we were dazzled by American invention, energy and confidence. Part of that was the Space Race, the sheer thrill of those never-before possibilities opening up in our lives. In Britain we flattered by imitation, new cars sprouted tail fins, chrome, white-wall tyres, wrap-around windows, cars were called Zephyr or Zodiac or Cresta, motorbikes called Thunderbolt, Starfire. But we concentrated on styling and surface impression, neglecting engineering advances underneath the chrome, while in Germany and even France they focused on better engineering. You don’t see many Ford Zodiacs or Vauxhall Crestas around now, because they’ve rusted away; planned obsolescence, another thing we copied from the USA. In the late 1960s I bought a second-hand Cresta, less than 10 years-old; it was very cheap because it was falling apart.

Somehow, few people in Britain seem to have held a resentment at the way the United States treated us post-war. During the Second World War, Britain went from being a creditor country to a debtor country, using all its foreign reserves and borrowing from many countries, including from the United States in a Lend-Lease scheme. The U.S. ended Lend-Lease, not only cutting off financial support but triggering its repayment. Britain was on its knees financially, industry had been converted to military production, there was massive war damage to repair, civilian life had far from returned to a normal, productive working pattern. Maureen Waller writes in her social history London 1945:

"The problems facing the Labour Government were immense.... They were not made any easier less than three weeks after they came to power by the abrupt termination of the Lend-Lease agreement with the United States... without consultation... There was a popular suspicion that capitalist America had terminated Lend-Lease so suddenly [in reaction to] the Utopian vision of Britai's new Labour Government, with its socialist principles and promised - expensive - welfare state."

In December 1945 the economist John Maynard Keynes negotiated a massive loan from the United States, at 2% interest over 50 years; it was not all paid off until later than this (2006). Perversely, much of this loan was needed to settle the Lend-Lease debt to the U.S., and as part of the deal Britain had to open its home and Commonwealth markets to American business. Meanwhile, European countries including Germany were receiving Marshall Aid (not loans) from the United States to rebuild their economies.

Between the wartime allies, there was also an element of the United States looking to its future as the world's dominant power, welcoming the decline of the British Empire and helping to hasten that decline. An obedient, in-hock Britain was of advantage to the U.S., an independent economically strong Britain on the world stage was not.

I never heard a word about this growing up, not a word in my parents' conversation, on news programmes, at school. It was as if we were all living in a state of self-inflicted innocence of the realities. What I have heard repeated through all the decades, in crowing terms by politicians, is that Britain had a 'special relationship' with the United States. Yeah, right.

But as a boy I shared the excitement about space exploration, and this innocence was unspoilt by any knowledge of our huge debts to the U.S., nor by McCarthyism or what the United States was doing in Central America or elsewhere, the petty dictatorships propped up to serve U.S. interests. Newspapers and programmes in the 1950s and early ‘60s steered clear of anything controversial, and politics was treated in a narrowly national and party-political way. I think it wasn’t until the U.S. involvement in Vietnam was well underway that a more critical and sceptical view of the United States became widespread.

Chapter 7

Make Do and Mend

I grew up at a time and in the large part of the population which had a fear of falling into poverty and also a pride in rising above it, most of all a pride in hard work and being careful with money.

It made family life hard work; every penny was watched. This was the way of life for my parents in the ‘50s and had been for their parents in the more difficult years before. The paper from packs of butter was kept to grease cake tins, socks were darned (how many do that now?). Jerseys were knitted, never bought; old jerseys were unpicked to re-use the wool. My mother’s evenings were spent needles in hand or at the sewing machine, all skills passed through generations of women, ever-busy, literally home-making. Curtains were never bought ready-made. I wore clothes my mother had made, or scrimped and saved for if she couldn’t make them, like school uniforms or shoes which were a major expenditure to be budgeted for just because they couldn’t be made at home. Sheets were ‘turned’, which now must be explained: sheets were cut down the middle where they had worn most, so the less-worn edges could be sown together and postpone the cost of buying new sheets. The sheer time-consuming labour of this!

People like us had relatively few clothes, thought of as those that were everyday wear and those that were ‘for best’. Children’s clothes were often ‘hand-me-downs’ from older siblings and neighbours; it was an unusual event for a younger child to have a new item of clothing bought. Clothes were taken care of and made to last; the qualities and uses of different fabrics was considered; I don’t hear these names mentioned much now, they seem exotic: barathea, gabardine, calico, flannel, winceyette, serge, terry, seersucker… Denim is one fabric which was never mentioned and is everywhere now.

Men often wore long johns in winter, and not only for working outside because workshops and factories and garages were usually unheated. We wore vests almost all the year; T-shirts had not yet reached us from the USA nor those strange skull caps with peaks.

There was a finely graded and sharply defined class system, which has since blurred, and a fear of falling on hard times, but how people lived then was not simply driven by these things. Make Do and Mend was also a virtuous way of life, not simply forced on us by economics and class. And this ethos stretched across class boundaries, surprisingly so. Where now it is commonplace to buy all your clothes, often for novelty rather than for usefulness, and to accumulate a great many of them, my parents’ generation and their parents made many of their own clothes, as did well-off upper middle-class families. In Invitation to the Waltz set in the 1920s, for example, the Curtis family are rich enough for the husband to have given up work, well connected enough to be invited to dine with local gentry and for the daughters to attend hunt balls and ‘come out’ as debutantes. But the daughters have learnt to sew, they make some of their own dresses and underclothes; a 17th birthday present for Olivia is a roll of silk to make into a fine dress. The mother is much younger than her husband but seems to have accepted the maternal duty of passing on to her daughters the skills of home-making, while the males of the household (her husband, his errant brother and the young son) seem simply unengaged in the busy female business of living; they just seem to stand around, get in the way. As well as the physical work, Mrs Curtis also sets the standards of behaviour and language for her daughters.

Prosperous and middle class though the Curtis’s are described as being, their social standing is below that of the Heriots with their hunting and hunt balls, and further below Lord and Lady Spencer; these distinctions are evident in all they do. But ‘character’ crosses these important class divisions; Lady Spencer likes Mrs Curtis, thinks well of her and how she is bringing up her daughters, and is genuinely friendly and supportive across the class divide.