Acadia

A once vibrant culture in modern-day Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Maine, lives on through its descendants, though absent from maps. Named for its lush beauty, it holds a profound place in history.

Acadia was a country, with a unique way of life, in the area of modern-day Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in Canada, and Maine in USA. Great efforts were made to destroy it, but for people who can trace their ancestors to 17th and 18th century Acadia, it is real, and defining. There is a wide diaspora, and a sense of Acadian cousinage.

Chapter 1

Land of Trees

Acadia does not exist on maps nowadays. It was so named in the early 1500s by a Italian sailor, Verrazzano, literally sailing past and noting how beautiful and unspoilt the North American coastline looked - like a paradise, the historical/mythological Arcadia of the ancient Greeks, “on a account of the beauty of the trees” [translated]. On old maps and documents, at a time when spellings had not become fixed, it had many variations - La Cadie, Lacadie, Acadia, Acadie - it’s the latter, francophone version I am using here-on.

Old maps are vague on exact boundaries but attach the name to lands on the northern Atlantic coastline including modern-day Maine, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Cape Breton and islands towards Newfoundland and the entrance of the St Lawrence River. But they weren’t called by those modern names then; it was all known as Acadie, and described as a “land of trees”.

Naomi Griffiths, historian and ethnographer who has specialised in Acadian history for well over 50 years, wrote:

“In 1953 I met students from New Brunswick at the University of London, students who spoke French as a mother tongue and who saw themselves as Canadian but for whom that identity was coloured by the sense of a strong Acadian heritage… In their telling, it was the history of a people who never had political independence but had developed a strong, unique identity nevertheless. … as important to my new acquaintances as a sense of Welsh identity was to my father’s family.”

I was eight years old in 1953, brought up to believe my stepfather was my father, unaware of my absent father, who was an Acadian. It took me many years to find my biological father. Meanwhile I learnt about Acadie and what it meant to be an Acadian, summarised here.

Doucet was one of the surnames of the original migrants settling in Acadie in the early 1600s, so the history is interesting to me. More generally it is interesting because Acadie is an example of a small migrant community creating a distinct sense of identity, an ethnicity and a culture, over a relatively short period of time, and then retaining this in following centuries despite fragmentation of communities in forced deportations, and despite powerful forces of assimilation in the many locations they re-settled, always without political autonomy. How this happened - how an Acadian cultural heritage came about - is as important as the catastrophe of mass deportation which afflicted Acadians in 1755. Today, there is not the original geographic Acadie but there is an Acadian cousinage across the world.

From around the 1400s Basque, Breton (and Celtic - Irish, Cornish, Welsh?) fishermen each year sailed to the shallow waters off Newfoundland and Acadie which were rich in cod; this was a delicacy in Europe. The long hazardous sailing was often made twice a year, in spring and summer; camps were set up on the coasts to salt the fish, and crews also undertook hunting to get animal pelts or traded with Amerindiens, as fur was also prized in Europe. Fur trading became an important part of European involvement in north America. The Acadie area was therefore known about in Europe, probably more in coastal communities and ports than in state/political circles.

Rivalry between France and England increased, around 1600, for control of North America and establishment there of what became known as New England and New France. England was trying to establish colonies further south on the coast (Virginia was the first, in 1607, with a thousand settlers by 1619). The rivalry was mainly mercantile, sometimes military-naval, and it was sporadic - these were small numbers of Europeans seeking to occupy vast territories sparsely inhabited by indigenous peoples.

In 1604, in Acadie, the French settlement of Port Royal was established on the Baie Française (later known as Bay of Fundy); Samuel de Champlain wrote that:

“the shores of this river are covered with numerous oaks, ashes and other trees” [tr].

There were other small expeditions until about 1608 when official (i.e. Crown or state-sanctioned) French exploration and settlement turned to the valley of the St Lawrence River and what became Québec. The first French voyages to Acadie were to set up trading posts and most of the people returned to France in the autumn, after many had died trying to over-winter there; and they were all men, mostly ex-soldiers, unlike the family-based migrations into the English colonies to the south. A few men remained in Acadie, but significant efforts to settle there did not resume until 1632. The noblemen Isaac de Razilly, Charles d’Aulnay and Germain Doucet (Sieur de La Verdure) sailed in 1632 with 300 men, a few women and children, plus animals, tools, seeds etc in three ships to establish settlements along the Baie Française. Other small fleets sailed, their efforts focused on fishing and the fur trade. Few families arrived to form permanent year-round settlements until the 1636 voyage of the Saint Jehan, whose passenger list is the only one known from this time. It noted 78 passengers including several families, some with children, and farmers and craftsmen.

In comparison with Québec and the English colonies at this time, ongoing settlement of Acadie was slow and small in number, hampered by French merchants’ focus on profitable fish- and fur-trading, and by rivalries between French leaders there claiming rights over parts of Acadie. By 1650 there were about 50 families, mostly in Port Royal. A total of 47 Acadian family names, some of whom had branched off into separate households or locations, were recorded 21 years later: Aucoin, Babin, Beliveau, de Bellisle, Betrand, Blanchard, Boudreau, Bourg, Bourgeois, Breau, Brun, Caissy, Comeau, Cormier, Corporon, Cyr, Daigle, d’Entremont, Doucet, Dugas, Dupeux, Foret, Gaudet, Gauterot, Girouard, Granger, Guilbaut, Hebert, Landry, Lanoue, Landry, Latour, Leblanc, Martin, Melancon, Morin, Pellerin, Petitpas, Pitre, Poirier, Richard, Rimbaut, Robichau, Savoie, Terriau, Thibodeau, Trahan, Vincent, many with spelling variants in censuses and other records.

Migration from France was not due to population-pressure. The population of France had declined steadily; life at the time for peasants was very impoverished, plagued by famine, decades of civil war, uprisings and religious strife, and circumscribed by feudal restriction. Life was bad enough, without hope of improvement, to prompt some people to opt for two or three months of hazardous sailing to make new lives in an unknown country.

Records indicate that migrants came from all over France and possibly from beyond its borders; since many had already migrated long distances on land to reach the Atlantic ports, they were likely the more robust and determined members of the population.

Climatic conditions were harsher than in Europe but these francophone settlers were fortunate in that the Mi’kmaq indigenous people were nomadic (rather than land-settling/cultivating) and friendly; the new settlers seem not to have had strong European prejudices against ‘les sauvages’, and learnt from the Mi’kmaq how to survive there.

In these early years, “the fur trade drew Acadians and Mi’kmaq into regular contact”, and there were intermarriages; Acadians learnt from the Mi’kmaq of how to survive in the harsh climate, “became adept with birch-bark canoes and snowshoes and probably relied even more heavily on Indian lore about dyes, herbal remedies, and edible roots and berries than did the Canadians” [i.e. settlers in Québec]. The relationship between a European and an indigenous culture in Acadie was more harmonious than probably anywhere in North America. The very small numbers of Europeans arriving in Acadia in the early years; that they were not part of a military or militant foreign incursion; that their numbers grew mainly from procreation rather than further immigration; and that they were self-sustaining so not competing for natural resources, may well have helped this rare example of cooperation and coexistence, as opposed to competition and conflict, between two peoples, incomer and indigenous.

It helped that the incomers were able to develop a productive marshland agriculture. They brought with them techniques for reclaiming land from the sea, which they could farm and also make salt from (for preserving fish and meat). “Most of the uplands of Nova Scotia were ice-scoured, hard rock massifs without agricultural potential…. there was no great river to draw the Acadians inland. Almost all lived at the edge of tidal marshland…” The Bay of Fundy has the greatest tidal range in the world, allowing barriers placed towards the low tide mark to gradually hold back incoming tides and reclaim fertile land for agriculture; these techniques were already in use along parts of the Atlantic coast of France and also the Netherlands. One leading settler described his rival’s very recent agricultural efforts at Port Royal:

“there is a great extent of meadows which the sea used to cover, and which the Sieur D’Aulnay had drained… bears now fine and good wheat.” [tr]

At Grand Pré the village founded by a group of extended families around 1682 overlooked a vast area of marshland in the Minas basin. The Grand Pré Acadians worked their way outwards, dyking off low-tide land section by section, building by 1755 nearly 19 miles of dyke walls to reclaim nearly four square miles of tidal marsh which became fertile, productive fields.

In 1699 a visitor from France, who lived with the Acadians for a year, described the countryside around Port Royal as “faultlessly beautiful” and praised the inhabitants’ hard work:

“It costs a great deal to prepare the lands which they wish to cultivate. To grow wheat, the marshes which are inundated by the sea at high tide must be drained; these are called lowlands, but what labour is needed to make them fit for cultivation! The ebb and flow of the sea cannot easily be stopped, but the Acadians succeed in doing so by means of great dykes…” [tr]

No other colonies in North America developed settlements based on the reclamation of salt marshes. Salt, a common commodity today, was much sought after in earlier centuries. It was essential both for preserving winter food supplies and preserving fish being shipped to Europe. With small numbers of settlers, land reclamation and the ongoing maintenance of dykes was only possible with communities, who probably did not know each other before migrating, working together for long hours, thus creating a strong sense of inter-dependence and surviving (only) in this way. What resulted was an ethos of self-sufficiency and self-reliance, a valuing of independence and autonomy, and valuing of family and community bonds as the essentials for survival.

Townships and villages were not usually formed as part of the Acadian settlement pattern. Instead, each extended family settled a favourable section of river-bank, and with the help of neighbours created dykes to extend the existing pastures, and also cleared land short distances inland.

Due to the great tidal range, and storms, the dykes were major constructions of timber, reed and clay, up to eight feet high and 15 feet wide at the base, with one-way channels (aboiteaux) to allow retreating tides out. Construction was very labour-intensive, as was their maintenance; initially, and if breached by tidal or storm surges, three years of fresh-water leaching could be needed to reduce the salt content to levels allowing grass and grain to grow.

European visitors also remarked on the Acadians’ skill in building canoes and small boats, and piloting them over long distances or in dangerous conditions. In this way, Acadian communities scattered widely and sparsely over large areas nevertheless managed to keep in contact. Travel was primarily by water; overland travel was difficult and slow in hilly and heavily wooded countryside. Little effort seems to have been made to link communities by clearing and constructing roadways; horses figure rarely in early censuses detailing each household’s farm and animals.

Acadian families were large and generations intermarried; there was some intermarriage with local tribes, and both Catholic settlers and the Mi’kmaq valued forms of marriage for the care of children. Married women often retained their family names, emphasising the importance of inter-family relationships. The extent of intermarriage with Mi’kmaq may have been more than census data indicates; one modern-day Michele Doucette has written about tracing her lineage back to the Germain Doucet of the 1632 migration, only to find her DNA indicated Amerindien ancestors.

The variously located Acadian communities seem to have been cooperative rather than competitive, and inclusive: some Mi’kmaqs were assimilated into the extended families and took the family name, and likewise other individuals were assimilated into families (as may be indicated by some of the names; there was a Doucet l’Irlandois, and a Doucet l’Anglais; was one simply red-haired or does the naming indicate the Irish origin of this individual? And was l’Anglais simply so known because he spoke English - but surely not the only one). I do not know if or how I am related to any of the Doucets mentioned here.

A recent report of archeological investigations of old Acadian settlements gave this context:

“In part because they created their own agricultural land, the Acadians had friendly, collaborative relationships with the Indigenous Mi’kmaq. In a place with such plenty, there was no need to compete for resources. There were even a significant number of marriages between the groups, which was unheard of in the New England colonies to the south, where Native peoples and Europeans were, at best, wary of each other. Heavily influenced by the Mi’kmaq, the Acadians developed a social structure based on communal cooperation that contrasted starkly with the rigid hierarchy they had known in France. This communal spirit was particularly helpful in organizing and carrying out the hard labor necessary to build and maintain the monumental dikes that held back the tides. ‘In France, if you were a peasant, you were under a nobleman’s control and had no real freedom,’ says Rob Ferguson, a retired Parks Canada archaeologist. ‘When the colonists came to Acadia, they suddenly had control of their own lives. They had their own farms and they could sell their crops. There was intermarrying between levels of society that would never have happened in France. In a way, they really did have a paradise.’”

It has been estimated that infant mortality was much lower than in contemporary Europe; food was more abundant and living conditions healthier as well as without the corvée, tythes and taxes, nor with the restrictions on travel and occupations that bore down on country people in Europe. A Breton lawyer noted in later years, when exiled Acadians failed to re-settle in France, that they had become used to a bountiful land, easy to cultivate, providing plenty of bread, meat, milk and butter, and free of oversight by landowners, clerics, nobility and bureaucrats. Health and fertility were also favoured by the hard physical work needed to survive, and a sense of interdependence by the fact that much of this work had to be communal.

By the 1670s the Acadian population was still small - probably not much over 300 (in contrast with Massachusett’s 20,000 population at the time), but it had reached the point of being self-generating, as opposed to reliant on further immigration for growth. The 1671 census revealed young families with high birthrates, some grandparents young and healthy enough to still be producing more children - such as Abraham Dugas aged 55 and Marguerite Doucet, 46, who had eight children, the two youngest being seven and six, while the two oldest daughters were married: Marie (married to Charles Melanson) already had four children the oldest of whom was seven. Port Royal had 68 families, and there were small family-communities elsewhere; some settlements were un-surveyed in the census and some Acadians evaded the census. Port Royal was youthful, it had 114 children under 10 years, 162 under 15 in 1671. This all indicates that Acadian communities were living healthy lives in a healthy environment, with abundant food and little of the disease which blighted European populations (in France, 25 out of 100 children died before age one, another 25 never reached 20 years).

The census also detailed each family’s ‘holdings’ - cattle, sheep, acres of cleared and uncleared land; there were big variations, but there is no indication of servants being part of any households. There were three Doucet families in Port Royal:

Pierre aged 50, a mason, his wife Henriette Peltre 31, their five children (Anne 10, Toussaint 8, Jehan 6, Pierre 4 and a 3-month old), seven cattle and six sheep, and four acres of cleared land;

Germain 30 (so not the Germain of the 1632 voyage), a farmer, his wife Marie Landry 24, three children (Charles 3, Bernard 4, Laurent 3), 11 cattle, seven sheep and three acres of cleared land being farmed; and as noted above:

Marguerite Doucet, 46, married to Habrahan Dugast 55, an “armurier” (metal-worker or blacksmith) and their seven children Marie 20 and Anne 17 (both already married), Claude 19, Martin 15, Marguerite 14, Habrahan 10, Magdeleine 5; 19 cattle, three sheep and 16 acres of cleared land.

Some people, especially craftsmen, had animals but no land; it is probable that there was bartering, labour was exchanged (especially needed on the larger holdings), and grazing was on commonly held open land with the cleared crop-sown land being fenced. What appears from the census is a fast growing community which is interdependent, with full-time all-family working, of necessity. This combination of independence from outside authority and community-interdependence then became established as an ethos over the years.

Just 15 years later, the Acadian population had nearly doubled, as recorded by the 1686 census. There had been some immigration bringing new family names to Acadie, including from Québec, but the increase was mostly ‘natural’ - people were fertile and the children lived; the community was self-generating demographically. Port Royal, from which some members of extended families had moved to enlarge smaller settlements or settle new areas, had 95 families remaining in 1686. Reports by visiting French officials commented on the beauty of the lands and rivers; the acreage of land cleared had doubled, herds of cattle, sheep, goats and pigs likewise; as well as agriculture the trades of carpentry, spinning and weaving, shoe-making, masonry, tool-making and boat-building flourished and passed down the generations; more dyked land had been reclaimed at Beaubassin, Minas and Pisiquid; connections with France had been maintained, and trade with Massachusetts flourished.

Bartering was commonly used within communities, but surviving trade documents indicate coinage was also used and accumulated. The Acadians had “shown a good deal of commercial skill in turning an accessible location that was a severe military disadvantage into a clear economic asset.”

Doucets crop up at every point in this story of Acadie. One had the same name as my grandfather: in 1699 a Joseph Louis Doucet, married to Duprée Doucet, was recorded, and another, Pierre Doucet, married a “Femme Mi’cMac”.

Although there was undeveloped marshland still available in the Port Royal area in the late 1600s, Beaubassin, Minas and later Cobequid were starting to be settled at this time and expanded quickly. With large multi-generational families, it may be that young people preferred to move away and set up on their own, and were attracted by the greater potential of these larger areas further up the Bay of Fundy. Trade was flourishing with the New England colonies, which both French and British officials at Port Royal sought to limit, and the more distant settlements of Beaubassin, Minas and Cobequid probably allowed the Acadians there greater freedom to trade. At Beaubassin and the Minas Basin:

“the largest farms contained up to 50 head of cattle, 100 sheep, 20-30 hogs, a few horses, and 40-50 acres of arable” [land]. “Although French and English officials considered them indolent, they… achieved a far higher standard of living than all but the most privileged French peasants.”

Acadie was not a place of French colonisation in the way that Virginia, Massachusetts etc were products of English colonisation. The New England colonies represented “migration bound together with a clear purpose and organized to achieve it”, while Acadie can hardly be described as a colony of ‘old’ France at any point. In the 1630s Acadie was a matter of “a tiny handful of traders and missionaries, scattered from Cape Breton to the mouth of the Saint John and reinforced by the French fishing fleet.” It then grew under the efforts of its new inhabitants, with little or no external State/Crown assistance, to become not only self-sustaining but with agricultural surpluses on an annual basis sufficient to establish trading patterns. In the process, a distinctive Acadian character and culture had developed, as Dièreville (representative of French commercial interests there) recognised, speaking of them having an identity of their own, separate from France. He and other visitors around this time “write from the standpoint of outsiders, as people observing a society not their own”. Acadians did not regard themselves as, or behave as, colons.

The very sparse and un-sustained support of France for Acadie was related to the internal state of France: by 1600 there had been three generations of bitter and almost continuous fighting between dynastic rivals, with religious strife, uprisings of the poor and dispossessed, plague and famine. For decades to come, the priority for French monarchs was to ensure that France had a powerful central government, that economic and social conditions became settled enough to improve and be less impacted by religious hatreds and political enmities. Where French attention and resources could be spared externally, this was directed to Québec and the Caribbean colonies.

In the wider rivalry between New England and New France, the settlers of Acadie asserted their neutrality (‘les français neutres’) but resisted some English incursions. They were distrusted by the French as bad Catholics for not taking up arms on behalf of France, and were distrusted by the English for being Catholic and francophone, and friendly with the indigenous tribes (mainly the Abenaki) who were resisting English colonial expansion to the south. How militant the rivalry was varied over the years; treaties with local effect were made; there were raids on Port Royal and other settlements but, for the most part, life seems to have gone on as normal for Acadians, surely a good deal better and healthier than they might have experienced in Europe. However, English encroachment was attritional over the years: Port Royal was captured in 1710 and a new base, Annapolis, was built nearby. The Rivière Dauphin became Annapolis River. The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 recognised the British territorial gains, while returning Île Royale (Cape Breton Island) and Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) to France. Acadie became Nova Scotia (though much larger than present-day N.S. and with vague boundaries) but remained primarily occupied by Acadians and Mi'kmaq, with British forces confined to Annapolis and Canso (Canceau previously), and virtually no British civilian immigration and settlement.

Below and beyond English/French rivalries, despite occasional raids by pirates and New Englanders, everyday life went on for the flourishing Acadian communities. One official sent from France to be in charge of Acadie in 1701 was impressed by the prosperity of the Minas settlements he passed through, reporting that there was a large number of cattle and enough wheat grown to export in quantity; he noted (more ambivalently) the inhabitants were “most independent in character and accustomed to decide matters themselves”[tr]. In Port Royal he was told they would rather live under the English, who at the time were not interfering with their lives, than have their lives imposed upon from France. One francophone historian wrote:

“En plus de leur croissance demographique, les Acadiens, ayant compris qu’ils ne pouvaient pas se fier a la France, avaient commence a s’auto-gouverner” (with their growth in numbers [and prosperity], the Acadians, having understood that they could have no trust in France, have become self-governing).

Census returns around this time show that in Minas, Beaubassin and Port Royal there were about 350 adult males out of a population of 1,500, with about half the total under 15 years - signs of healthy, fast-growing communities.

The 1730s have been called a ‘golden age’ for Acadie. Between 1720 and 1744 the Acadian population more than doubled. Beaubassin, for example, grew from 127 in 1671 to 2,800 in 1748. Although Acadie became officially, or nominally, a British colony with the capture of Port Royal in 1712 and the Treaty of Utrecht, in practice the British presence was limited to the fort at Annapolis Royal (and that relied on trade with Acadian communities for supplies), and these communities chose deputies to represent them (in effect, universal suffrage long before Britain adopted this). The Acadian deputies went to the British officials and mediated, rather than officials regularly entering and interrupting community life. One long-running issue was the oath of allegiance (of Acadians to the British Crown), which communities were generally willing to take provided they were not required to bear arms. The oath took various forms over the years, and successive British officials took different views on it.

Another issue which rose and fell during these decades was the possibility of Acadian migration to the nearby Île Royale and Île Saint-Jean, ceded to France - or forced migration there. A few Acadians went to the nearby French islands, and most returned; the great majority of Acadians stayed put on what to them had become their ancestral lands. On this also, British policy varied over the years, as did the views of officials. Meanwhile, agriculture flourished which gave communities economic power (in trade as well as self-sufficiency) and - because it was based largely on the dyking system which was very labour-intensive and required ongoing maintenance - also bound them together. During this time there was virtually no British or other migration into Acadie.

From the regular trading of meat and grain it is clear that Acadian communities had members who were bilingual and literate. The sense of community and kinship, of inter-reliance rooted in daily hard work on their lands and trading of produce, had evolved pragmatically as the essence of what it meant to be Acadian.

This sense of a distinctive identity was shared across long distances - this was a small population spread across a large area, with a small number of scattered settlements, albeit each prospering. Travel by land was slow and difficult, but the coastline and river valleys even where unsettled were well-known to Acadians from fishing and trading. The physical distances, and differences in soil and seasonality, seem to have strengthened rather than diluted the sense of a common identity and interest.

What I found remarkable when I started to explore my paternal heritage was that in approximately 150 years an Acadian ethnic identity and culture was created, and secondly, that it has persisted since then despite an event which, literally, dispersed and fragmented communities, and despite the tendency for exiles to assimilate into their new ‘host’ societies if only for reasons of economic survival and acceptance.

I was deprived of knowledge of the Acadian part of my heritage for half my life. It is a remarkable heritage; the historian and ethnographer N E S Griffiths (not an Acadian, so no special pleading!) puts it better than I can:

“European settlers in the Maritimes eventually developed from a migrant community into a distinct Acadian society… Acadian culture not only survived, despite attempts to extinguish it, but developed into a complex society with a unique identity and traditions… capable of surviving extraordinary travails… allowed a considerable number of those sent into exile to endure as a community…[with] a strong sense of their origins in Acadia.”

In the decades from 1710, British control and physical occupancy of Acadie/Nova Scotia remained weak and small in numbers. Of the British occupiers it has been said: “their frustration increased with the obvious development of the Acadian settlements, which flourished demographically, economically, and socially”. The population had increased to over 11,000 by 1748, from about 2,500 in 1714.

In 1744 war broke out again in Europe between France and Britain, prompting a French expedition from Île Royale/Cape Breton to attempt the recapture of Annapolis Royal. As they travelled overland these forces sought support from Acadian communities, sometimes with threats. Despite the fact that the attack failed, and that very few Acadians had joined the French forces, it showed to some officials how perilous was the position of a small, under-resourced British force governing a large, prosperous and independent-minded population; differences of language and religion added to this sense of insecurity. British officials differed, some taking the view that Acadians were “a very ungovernable people and growing very numerous”, others that the failed French raid on Port Royal proved the opposite: “to the breaking of the French measures, the timely succour receiv’d from the Governor of Massachusetts, and our French inhabitants refusing to take up arms against us, we owe our preservation.” In fact, the populace of New England colonies to the south was both much more numerous and rebellious, with serious rioting against government control, at this time.

Notable is the burning of Beaubassin settlement in 1750. This was carried out by a Mi’kmaq group at the urging of a militant itinerant Catholic priest, Father Le Loutre, keen to spark Acadian settlers into revolt. It failed. A major Acadian settlement was destroyed in the effort - Acadians en masse did not take up arms against the British administrators who were at the time moving from Annapolis Royal to a stronger new fort at Halifax.

The years around 1750 were fraught with tension and distrust between England and France, whether in Europe or North America. There were more French raids (ineffective but reminders of what might happen) on British-held but francophone-occupied Acadie/Nova Scotia: there was a major French stronghold, Louisbourg, on nearby Île Royale/Cape Breton (captured by a Massachusetts force in 1758); and there was the Stuart uprising of 1745 in Scotland which France supported. War flared up repeatedly in Europe, and attitudes hardened on both the British and French sides among officials and forces in North America.

The creation of Halifax in 1749 was accompanied by British efforts to settle new, Protestant migrants there, expecting them to be more amenable; some 2,000 arrived in 1750-51, with more following. They were unprepared for the harsh conditions and fared badly; instead of mingling into Acadian communities as had been intended (and may have helped them adapt) they formed the new towns of Dartmouth and Lunenberg, or swelled the Halifax population. Over the years, others arrived, including many Scots and Irish, displaced from their homes or unable to prosper there under British rule.

Acadie/Nova Scotia was a border country between two warring European nations, one with powerful New England colonies nearby and powerful naval forces, the other with a New France colony (Québec) less engaged, like France itself, and more distant, a land journey through hundreds of miles of dense wilderness or a difficult sea voyage. Acadians were caught in the middle, their priority was being allowed to continue living on the lands their ancestors had settled, whether or not realpolitick required them to live under French or British administration. Insistence on their distinctive non-British, non-French identity, hence their non-combatant status, had preserved them for generations, until a new British governor, Colonel Charles Lawrence, an impatient man, lost patience, facing increased French challenge and with a ‘foreign’ population refusing to fight for Britain, maintaining its independence. It seems no document from England to Lawrence instructed him explicitly to deport the Acadian people; previous governors had periodically raised deportation as a possible measure, as had Lawrence, but responses from England were vague, non-committal and often very delayed. However, it was in the name of the British Crown that Lawrence took the decision and with British military/naval support that he carried out a brutal and sustained campaign of capture, destruction of property, division of families, and deportation, over an eight-year period.

In 1755, from his new base in Halifax, Lawrence called 15 Acadian deputies from the Minas area to meet, unarmed, and agree an oath of total, unreserved allegiance as subjects of the British Crown; they gave the answer as before, saying an exemption granting them non-combatant status had been accepted previously, for many years; if Lawrence insisted on changing this they must consult their communities. Instead, the deputies were imprisoned in Halifax. Lawrence summoned deputies from elsewhere and on 25-28 July 1755 30 men from Annapolis Royal and 70 from the Minas communities arrived, with a letter signed by 270 more from other settlements promising continued peaceful (and non-combatant) allegiance. Lawrence had not actually promised them that in return for signing the new oath they would be left in “peaceful possession” of their lands, or stated that not signing would result in deportation. But, before meeting this second larger group of Acadian representatives, Lawrence and his advisors, with urging by the governor of Massachusetts, had already decided “to send all French inhabitants out of the Province”.

Chapter 2

Le Grand Dérangement

This was Lawrence’s ‘final solution’ response to the decades of Acadian neutrality, and the official end of Acadie. All the deputies in Halifax in July 1755 were imprisoned while ships were prepared. It seems no attempt was made to inform the families and communities they had come from, let alone to re-unite them before deportation. In fact there was a deliberate policy of breaking up communities to be sent to different locations:

“to prevent as much as possible their Attempting to return and molest the [new] Settlers that may be set down on their lands…”

Or if they were sent to nearby Île Royale or Île Saint-Jean it was feared they would simply strengthen French forces there. So, the description of this policy by modern-day Acadians, ‘scattered to the winds’, is no hyperbole.

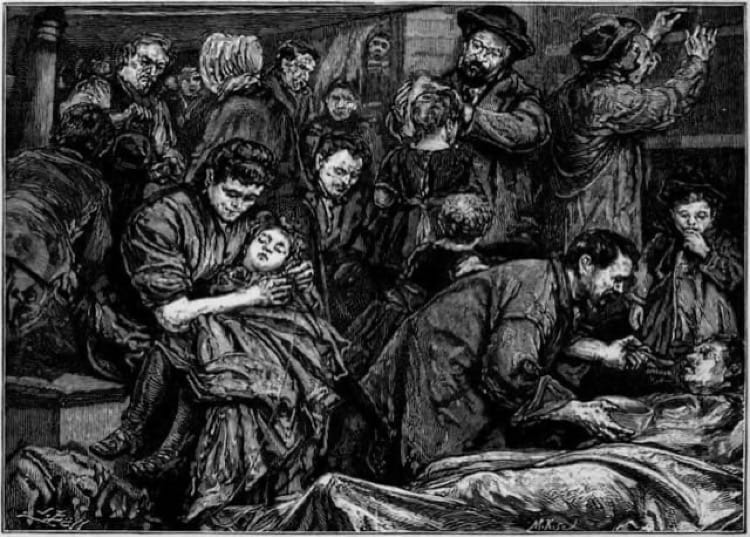

Families were broken up. Before news of the deportation decision had got out, Acadian men in most of the major settlements were called to meetings locally, where they were captured by British soldiers from the New England colonies and taken to waiting ships. Women, children and the elderly were rounded up later and transported. Parish and family records were lost or destroyed. A history of Colonial America 1585-1776 states:

“The Acadians …were rounded up and deported… losing much of their property in the process, for their settlements were destroyed to prevent them being reoccupied … many perished on the journey or died of sickness. …others made heroic efforts to return to Canada to fight for their lands once more. The episode revealed the harshness of war for a civilian population caught between the ambitions of two competing powers.”

In Acadian history this is called ‘Le Grand Dérangement’. In English, ‘derangement’ well conveys the social and cultural - psychological - damage of this deportation and family-breaking/scattering. It was not a single, awful event; it was an eight year campaign of persecution, finding and destroying Acadian communities. British forces occupied main settlements and burnt them, progressing inland to smaller communities. The History of the Canadian Peoples states:

“Terror swept through the Acadian communities as the awful reality dawned. At Chignecto the men were summoned to Fort Cumberland… and held in captivity; eighty of them escaped by digging a tunnel and escaped with their families into the woods. The Acadians near Piziquid were imprisoned in Fort Edward. At Grand Pré the parish church served as a makeshift prison until the transports arrived. Annapolis Royal was a different story. There the Acadians had prior warning, and many managed to escape… Whether free or captive, no Acadian was spared the horror of what followed. The British soldiers put Acadian homes, barns, and churches to the torch and rounded up their cattle. In a few hectic days in the late summer of 1755 the golden age of Acadian life came to a tragic end.”

Colonel Edward Winslow, in charge of the deportation from Grand Pré, reflected later in his diary that this was “the worst piece of Service that ever I was in… ”.

One of the Beaubassin families torn apart by the deportation was that of Francois Hébert and Marie-Ann Bourg; their daughter died at sea, one son arrived in Ile d’Orleans, Québec, in 1756, two other sons were in St Pierre & Miquelon by 1766 where they married. Francois Doucet and Marie Poirier were among other Beaubassin Acadians who had reached Becancour in Québec by the autumn of 1758.

Acadian families in the village of Belle Isle in the Annapolis valley, getting word of the forcible arrests and deportations, fled before the British soldiers arrived. About 300 of them (different accounts give different numbers), led by Pierre Melanson, trekked across the high ground to the Baie Française/Bay of Fundy. There they had to overwinter, in freezing temperatures and high winds, without shelter. By the spring only about 90 of them had survived, and Melanson died soon after; they were helped to cross the Bay by the Mi’kmaq, and fled into what is now New Brunswick. A driftwood cross was erected where so many had perished; this was later rebuilt in stone, the so-called French Cross near Morden, N.S. Similarly, a metal French Cross marks the deportation site at Grand Pré.

Many of the Acadians who escaped capture and hid out in remote areas were captured later by British rangers, or forced out of hiding by hunger and harsh winter conditions. Others fled inland to the small Acadian communities in what became New Brunswick, including 232 families who captured the Pembroke, a ship intended to take them to South Carolina, and sailed it up the St John River where they settled in late 1755; this group included Doucets, and from the number of children (70 boys and 92 girls, among 33 men and 37 women) the trauma of this family-wrecking event can be imagined. This is one of the few groups of deportees where names and numbers are known. Then, three years later, they were attacked again by British forces and fled further inland towards the then-undefined borders of Maine and Québec.

The Mi’kmaq (and the Malecite and Abenaki peoples in more inland parts of Acadie) resisted and fought against the British control and occupation of Acadie. Halifax, capital of modern Nova Scotia, was being established in the years leading to Le Grand Dérangement, as the British started planning to occupy, in the sense of populate, Acadie. It was built in a well-sheltered bay about midway along the Atlantic coast; the Mi’kmaq considered the Baie Chibouctou area their ancestral home, and so Halifax was repeatedly attacked by them. In the 1740s-50s Governor Cornwallis had tried to get the Mi’kmaq to sign an oath of allegiance (total, no non-combatant proviso) to the British Crown, and was as unsuccessful as with the Acadians. The Mi’kmaq gave an answer similar in spirit to the Acadians’ responses, recorded in 1749 as:

“We are masters independent of everyone and wish to have our country free. The land where… you are building dwellings, where you are now building a fort, where you want, as it were to enthrone yourself… this land belongs to me, I have come from it as certainly as the grass, it is the very place of my birth and of my dwelling.”

It was that sense of rootedness and entitlement that the Acadians and Mi’kmaq shared (and apparently respected in each other as they had lived alongside for many years) - and why the enforced deportations were justly termed Le Grand Dérangement.

Rounding up and deporting Acadians continued until 1763 when the Treaty of Paris ceded control of Acadie to the British Empire. At the time of Le Grand Dérangement there were over 300 Acadian family names, some with several branches; there was a Doucet dit Laverdure family, and Doucet dit Lirlandois and Doucet dit Mayard (or Maillard) families (‘dit’ meaning ‘known as’ - to distinguish large extended families that had developed over decades from common ancestors, i.e. the Acadian primacy of family-connection again).

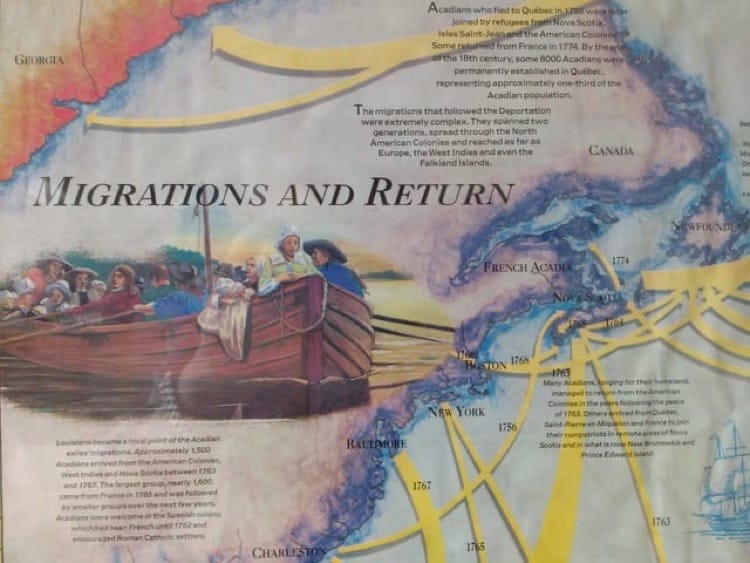

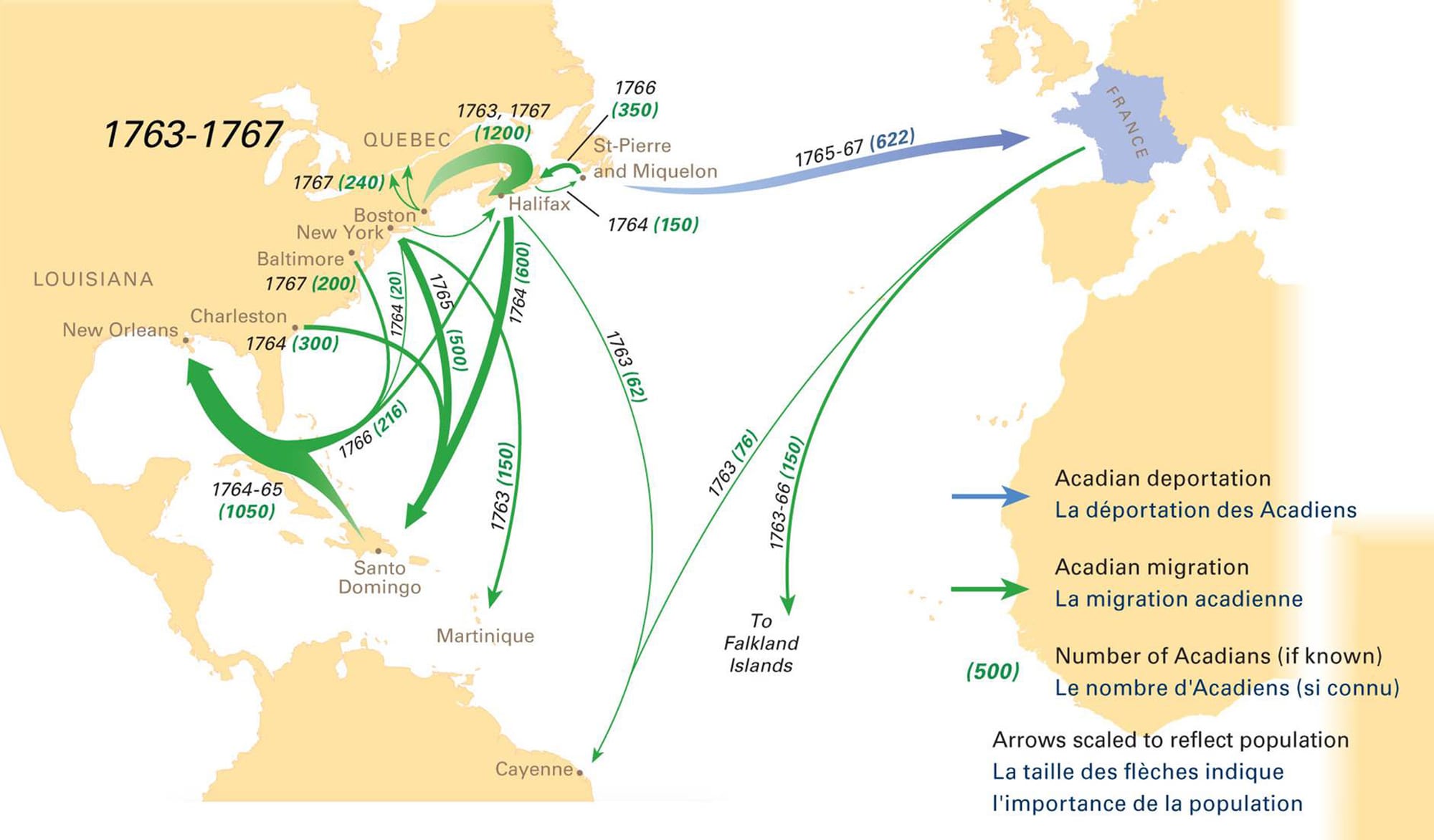

Overcrowded ships sailed directly or indirectly to the New England colonies, to France, to French Caribbean colonies (St Domingue, Martinique, Guiana), to England and even to the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic; some transport ships sank (three of four ships entering English/French home waters sank; one landed at Falmouth). Little or no food and water had been provided on the ships for the numbers carried, and some Acadians died en route or arrived in very poor condition. Their arrival was unwelcome in all the New England colonies, and no provision had been made for them; in many cases they were held in ships in harbour over winter, in the freezing, overcrowded insanitary conditions in which they’d travelled, with minimal provision of food and necessities.

Many deported Acadians ended up in Louisiana eventually, where the largest Acadian exile community developed and remains today (Cajun is a derivation of Acadian). Some, particularly from the New England colonies, gradually made their way back north to Acadie - which, in the meantime, had been re-populated. Others were sent by the colonies to England. Though ‘scattered to the winds’, the Acadian bonds of family and community remained; deported groups managed to trace each other, communicate across long distances, avoid or escape from the worst locations such as St Domingue and re-coalesce in preferred locations. However, some family names (recorded as among original settlers in Acadie) disappeared altogether from later records, possibly lost at sea during the forced dispersal, or succumbing to disease and starvation. Some 10,000 perished according to contemporary French records.

Several groups of exiled Acadians arrived in the colony of New York; one ship had been blown off course by a hurricane-force storm to Antigua and survivors completed the five-month sailing to New York “poor, naked and destitute of every convenience”. Many had succumbed to a smallpox outbreak. In neighbouring Connecticut, Acadians were separated to fifty towns and their movement strictly controlled; resistant to these measures, almost all the 666 surviving Acadians petitioned France in 1763 for transportation there. Nothing came of this, and some exiles escaped to St Domingue (unaware of the fate which awaited them there) and about 240 others found a ship which transported them either to Québec or Nova Scotia.

At least one branch of the Doucet family was among Acadians transported to the British colony of Massachusetts, arriving in late 1755 in a destitute condition; one account states:

“The ships were overcrowded, and passengers frequently died of disease, cold and starvation. Parents complained that their children were removed from them and distributed to English families as ‘nothing more than slaves’”.

This removal of children and able-bodied men to work for settler families happened throughout the New England colonies, and was hated by the Acadian exiles as a further shattering of family bonds; in South Carolina “in many cases indentured Acadians had to be bound in irons and forcibly removed from their families”. Some Acadians tried to escape into the hinterland, and two groups were captured and brought back in case they joined amerindian tribes hostile to the colony. Others escaped in a boat which, sinking, was beached in Virginia, then obtained another boat which they had to beach in Maryland as it too was unseaworthy, but they repaired the “wreck” and eventually reached Nova Scotia where they joined small French forces and harassed British forces.

Massachusetts received more exiles than the other New England colonies; some were shipped to other destinations. As in other colonies, those who remained contracted smallpox upon contact with the Anglo-American population, and this not having been present in Acadie they had no natural immunity so many died. Survivors were divided up and distributed throughout the colony, obliged to work and children forcibly indentured to Anglo-American families. By early 1756 ships’ captains were forbidden from hiring Acadians, who were confined to allotted towns on pain of fine or flogging. A glimpse of the pain caused by successive family separations is given in a collection of contemporary documents: a Marguerite Dowsett (Doucet?) “sollicite d’etre envoyée à Newberry” and a “Peter” (Pierre?) Doucet sought “Permission de demeurer dans le Comté de York” because his parents had been living there for several years; I can find no indication if these requests were granted, but they sound like two examples of what was very common - scattered family members desperately trying to link up.

Joseph Doucet and his wife Anne Surette petitioned in 1763 for 179 families in Massachusetts to be sent to France; this failed, but two petitions later they were allowed to leave the colony. In the Massachusetts town of Ipswich there was Marie-Josephe Doucet aged 65, wife of Francis Landry aged 67, both “infirm”. Eventually, in December 1767, 147 Acadian families from Massachusetts were granted land to settle in Baie Sainte-Marie, in Nova Scotia (peninsular Acadie), Governor Franklin ignoring the ban on Catholics being granted land.

As the Massachusetts restrictions were relaxed, Acadian groups reassembled, failed in efforts to migrate to France, and some left for St Domingue, others escaped to Québec and the islands of St Pierre & Miquelon. Those who remained demanded work and better conditions, or resettlement in Canada. The latter was permitted from 1766 and, according to one account, many of those leaving, unable to afford passage by ship, walked northwards for four months either to Québec or to what became New Brunswick, finding their old Acadian homelands already occupied by new English inhabitants (12,000 had settled there by 1763).

In Georgia the destitute Acadians were simply ignored by the colony at first. To avoid starving, some acquired or already had skills to work in shipbuilding and the plantations, others migrated to St Domingue where many died of disease. Another group acquired ten open boats and in spring 1756 sailed northwards to return to Acadie; by July/August seven of the surviving boats and 9o of the original 200 Acadians were detained in Massachusetts and prevented from travelling on to Acadie.

One account of Acadians settling in Québec includes a modern-day descendant’s family-memory that her ancestor Etienne Mignault was captured and taken to Georgia where he and others were treated as slaves on the plantations for many years; they were chained up at night, except for one night when he managed to escape and after many months of walking reached the St Lawrence River where he searched and eventually found his wife Madeleine Cormier. She had escaped capture during the deportations and made her way to Québec; they then went to Becancour and settled among other Acadian refugees.

When Acadians transported to Maryland were kept on the ships in harbour for months over winter, the ships’ captains complained that Maryland had given no provisions for these hundreds of prisoners, many of whom died of starvation or disease. Hostility to the Acadians was fuelled by the (unfounded) belief that they were allied with Indian tribes which had been attacking outlying settlements in Maryland and other English colonies. When eventually released from the ships, surviving Acadians depended on charity from a hostile public. Acadians were partitioned out in small groups across the colony; laws were passed limiting their movement (soldiers were permitted to shoot Acadians on sight if they approached the western border). Acadians were deemed to be vagrants to be jailed if they found no employment, and Acadian children could be ‘binded out’ (sent to work for settler families). In late August 1756 the Maryland Governor informed Colonel Lawrence that:

“none of the French that were imported into this province have been suffered either by land or water to return” [to Nova Scotia].

Of the 973 Acadians arriving in Maryland in 1755, only 667 had survived by the 1763 census.

In Pennsylvania similarly, the 454 Acadians arriving were first imprisoned on the ships where many became diseased, then quarantined on an island, then separated around the colony; but most townships refused to accept them and the Acadians refused to be dispersed, remaining in Philadelphia’s slums. Efforts were made to forcibly apprentice Acadian children, which were resisted. The desperate (described as “mutinous”) Acadians begged to be allowed to leave Pennsylvania; in 1763 they notified France of their wish to travel there, to no avail, and in 1764 many took up the French offer to migrate to St Domingue as labourers carving a naval base out of jungle; many died of tropical fevers and their children of malnutrition and scurvy. Those remaining in Pennsylvania joined their compatriots from Maryland in a mass exodus to Louisiana in the late 1760s.

A 20 June 1763 list of Tous Les accadiens qui Sont dans la pinsilvenia includes “Jean Doucet Voeuf [widower] avec quatre enfants”. It includes many single men and women, some identified are widows or widowers, with attached children, some of whom are “orphelins” (orphans). In other cases a young person is listed with father-less and mother-less children attached, such as:

“allexis Landron avec cinq freres et Soeurs ny pere ny mere…

Marie melanson fille avec Sept freres et Soeurs ny pere ny mere…

ollivier Thibodeau magdelaine thibodeau Sa f’'e avec Six enfants et un orphelin…

Pierre Bro garçon sans famille…”

Reading the list, another indication of the family-shattering nature of the deportation, it’s hard not to weep.

The hostility of Maryland and Pennsylvania to the Acadian exiles forced onto the shores of these two colonies is surprising, in view of Maryland’s origins as a refuge for persecuted English Catholics, and Pennsylvania’s origin as a Quaker colony tolerant of religious and political differences. An 1858 publication of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania reflected that the arrival of the Acadians was at:

“certainly an unpropitious time… when an Indian and a Frenchman were looked upon with equal horror… French and Indians were advancing in victorious array. General Braddock was defeated in July 1755, and every English settlement on the seaboard trembled for its existence.”

The same publication notes that “no less a sum than £7,500, currency, or about $20,000” was spent in supporting and assisting the Acadians from November 1755 to the late 176os. Or in trying to assist them, because again there was a stubborn clash of mindsets and a mutual incomprehension: Pennsylvania wanted the Acadians to disperse around the colony, accept tools, farm animals etc to get them started and then become self-supporting, while they insisted that they were prisoners-of-war:

“…give us leave to depart from hence… send us to our nation… to join our country-people…[or] we desire that provision be made for our subsistence so long as we are detained here… we will never consent to settle here”.

A Doucet family was amongst those deported to Virginia, where the colony refused to let them disembark, keeping the ships in harbour for four months through the winter until survivors were taken to England. Some 1,200 arrived in 1756, at Falmouth/Penryn, Bristol/Stapleton, Liverpool and Southampton. It is unclear why the ships went to several different ports - possibly to further scatter Acadian coherence, or to spread the burden on the places where they arrived? But nowhere had provision been made for their arrival, and there were already hunger riots in England.

At first kept on the ships and then poorly housed (described by a French visitor as “dans la situation la plus déplorable”), smallpox, scurvy, exhaustion and starvation reduced the Acadian numbers; seven years later the 753 surviving from the original 1,200 were sent to France. Included were Pierre Doucet and Blanche Doucet (unclear if they were a married couple, siblings, or what) and a Charles Richard is listed in this group of three (either that is a mistake, or he may have been the brother or father of Blanche, and Blanche therefore the wife of Pierre). We do not know if this was the same Pierre Doucet, from the Chignecto community, who was one of the deputies summoned on a previous occasion, in 1749, when all Acadians had been pressured to swear total allegiance to the British Crown. Pierre and the other deputies did not, in effect, say yes or no, did not gain agreement from their communities; as before, they insisted on Acadians’ independence and right to continue living on their lands, and were allowed to - until the same demand by Colonel Lawrence in 1755 resulted in Le Grand Dérangement.

The 753 surviving Acadians in England had been promised good land to farm in France and assistance; much less was delivered by France than promised, but they failed to settle there mainly because of their refusal to accept the narrow, dependent, circumscribed lives of French peasants of the time, and their loyalty to Acadian family identity. This group and almost all of the ‘scattered to the winds’ Acadians had a “quite extraordinary level of communication” over long distances. In the words of one historian:

“records during the twenty-five years they remained in France show an extraordinary knowledge of where sisters, parents and other relatives were and a continuing concern for their welfare. Although divided into widely separated groups, the Acadians confronted their exile as a community.”

So, in 1785, over two-thirds of the Virginia/England/France deportees chose to sail to Louisiana, in seven ships, to join the Acadian community already there, some 30 or more years after they had been forced out of Acadie.

Refugee Acadians on New Brunswick’s upper coast in the Miramichi area were mostly women, children and the elderly who had fled their homes after the men were removed, and had only what they could carry on their backs. The governor of Canada described their plight:

“Acadian mothers see their babies die at the breast not having the wherewith to nourish them… Many have died. The number of sick is considerable, and those convalescent cannot regain their strength on account of the wretched quality of their food…” [tr]

After a dreadful first winter, several hundred moved to Québec where they remained until it was captured by the British in 1759. Others attempted to scrape a living from the infertile, rocky soil or from fishing, until in 1758 British forces attacked and dispersed the settlements.

In the Petit Codiac river valley, near where the future border between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick (Acadie peninsulaire and Acadie terre-firme) would fall when the latter was carved out of Nova Scotia in 1784, Acadian settlements had not been disarmed like coastal settlements on the Baie Française and elsewhere; the Petit Codiac Acadians reacted with armed resistance to British forces. Joseph Broussard dit Beausoleil and his brother Alexandre are venerated in Louisiana, where they ended up, for leading a guerilla-type resistance. However, capture of Louisbourg, the French fortress on Île Royale/Cape Breton, in 1758 reduced hope of French support, and superior British forces led to the surrender of most of the Petit Codiac settlements in the winter of 1758/59. The survivors were detained in Halifax until 1764, when they prepared to sail to St Domingue but on hearing from compatriots of the dreadful conditions there most of them sailed instead to Louisiana in November of that year. However, a few settlements hung on in the Petit Codiac area, attracting further British attacks in October 1761, from which many hundreds of prisoners were taken to Halifax; some Acadians remained, taking refuge in the forests and returning when it seemed safe, so maintaining a few settlements until in 1764 these were ‘allowed’ by the British government.

A census in 1767 on the small northern islands of Île St Pierre et Miquelon (which had been ceded to France) shows in small scale the scattering/family-shattering effect of the deportations. The census totals 551 Acadians residing on the islands, in family-groups plus some individuals; but many of what are shown as the 97 families are in fact fragments of families, much smaller than those noted in the earlier censuses of Acadie, with the first family member noted often as widow of, wife of, son of, and with brothers-in-law, nephews and nieces tagged onto many of the part-families listed. There are also separate, un-family-ed, individuals - there were none such in the earlier censuses. So this was a disparate, rag-tag group of 551, coming from many different places: the census notes they came from several English forts, from Boston, Halifax, Louisbourg (presumably the first places these captured Acadians were held in 1755-63) and from Chedabouctou, Pisiquit, Beausejour, Île St Jean (probably their original settlements), and in many cases no place of origin is entered under the “venue d’” heading. Only one family seems to be indicated as original inhabitants of the islands. Included in the census were three Doucet families:

Françoise Doucet aged 25, her husband Alexis Renaud dit Provençal 35, sons Pierre and François both aged one and Françoise shown as born “en cette Colonie”, Alexis’ nephew Jacques aged 15 and “La Veuve” (widow) Renaud aged 71;

Anne Doucet aged 38 and her husband Joseph Comeau 41, their children Germain 9, Etienne 6, Modeste 4, and Louise 1 who was born there, plus Marin Doucet aged 18 brother of Anne;

Michel Doucet aged 29, his wife Louise Beliveau 27, their children Joseph 4 and Charlotte 1, and Michel’s brother Jean aged 21.

Included in the family of Jean Bertrand and Marguerite Blanchard, both 36 years, and their children Nicolas 3 and Marie 1, is “Anne Doucet, veuve Bertrand, 71”.

This small group of Acadian deportees sadly did not fare any better in the coming years. While in time they might have formed a coherent, sustainable community even on these small infertile islands, in 1778 and 1793 when British-French hostilities flared up yet again the inhabitants were deported again, buildings were razed and possessions destroyed, as before. Whatever happened to these poor people, infants in arms, grandparents in tow, is not recorded (that I have found); possibly some made it back to France, to join Acadians stuck in the slums of Atlantic ports. Some echo of modern-day migrations! These islands were not re-settled until around 1820, by Bretons, Basques and others, and were not self-sustaining until many years later.

Some of the Acadians transported to the New England colonies escaped and made their way, with French encouragement - none of this reflects well on France - to the slave plantation colonies of the French Antilles in the Caribbean. These turned out to be anything but safe refuges. In St Domingue (now Haiti) they were expected to work as labourers creating a naval base out of the jungle; food, shelter and conditions were intolerable, and tropical diseases endemic; typhus and smallpox killed many and the few survivors moved away when they were able to.

Less is known about Martinique: a ship carrying Acadian deportees from the Port Royal area was blown off course to the British Caribbean possession of Antigua, which dumped the 300 Acadians on St Kitts, which dumped them on St Eustatius (a Dutch island), which transferred them to French Martinique. What happened to them next seems unrecorded.

French Guiana, third of the Antilles, was in need of colonists but unappealing because of its climate; Acadians even on cold, infertile St Miquelon refused an invitation to move to Guiana for this reason - another example of these exiles’ extraordinary ability to communicate and care for compatriots across great distances. But France successfully recruited colonists for Guiana from across Europe, which later encouraged some Acadian exiles in France to join in. However, bad colonial administration, the overloading of meagre local infrastructure with too many colonists, as well as the climate and tropical disease, caused colonising efforts to collapse and most survivors left the island for France. By the late 1780s one Acadian family remained. By the 1794 census there were no Acadian surnames there.

There was even French encouragement for exiled Acadian families to occupy and settle the Falkland Islands, which the French official Bougainville named Malouines. Between 1763 and 1766 over 200 mostly Acadian settlers arrived there. But living conditions were very difficult, agriculture barely possible, and little assistance was provided. The venture soon came to an end (farcically) when the British landed to claim the islands, and Spain laid a claim based on proximity to South America. Bougainville withdrew, but what happened to the poor colonists is unclear; it seems a few remained, a few were left in Montevideo, and a few straggled back to France in a “more or less miserable state.”

Chapter 3

Acadie/Nova Scotia post-expulsion

With the Catholic francophone population driven out, by 1758 Britain had started to re-populate Acadie/Nova Scotia with Protestant migration from across Europe and from the New England colonies.

When the New England colonies rebelled in their fight for independence in 1775, Britain called on these recent re-settlers of Nova Scotia to fight on the British, so-called Loyalist, side. Few did, many claimed a “de facto neutrality” to just get on with their lives, while quietly sympathising with the rebel colonists. Ironically, this repeated the Acadians’ insistence on neutrality in the recent past, which had prompted the deportations and ‘scattering to the winds’ - ironically, a bitter irony.

The American War of Independence increased migration, thousands of Loyalists settling on lands granted by the British taking over almost all the former Acadian farms. They settled mostly in what became New Brunswick when the British Crown divided Nova Scotia leaving that name to apply to Acadie peninsulaire, and creating New Brunswick out of Acadie terre-ferme (‘mainland’). The Loyalist land grants also encroached on ill-defined native lands and pushed Nova Scotia's several thousand Mi'kmaq people from their ancestral lands. New settlers took over much of the rich agricultural land developed by the Acadians. This was foreseen; when planning the 1755 expulsion Lawrence wrote:

“If we effect their Expulsion, it will be one of the greatest Things that ever the English did in America; for by all the Accounts, that Part of the Country they possess, is as good Land as any in the World: In case therefore we could get some good English Farmers in their Room, this Province would abound with all Kinds of Provisions.”

Acadians detained in Halifax and other British forts were sent out to help the Loyalist and other new settlers occupy the farms from which they had been expelled, i.e. to work among the ruins of their former homes, making the destruction habitable and productive for the New Englanders supplanting them - imagine the distress of having to do this!

“When the first New England colonists came to Nova Scotia five years after the Acadians were expelled, they encountered a landscape littered with bleached bones of livestock and burned ruins of houses. The dikes had fallen into disrepair due to neglect and storm damage, and the new arrivals had no idea how to repair them. To get the dikes up and running again, the provincial government turned to 2,000 Acadians who had avoided deportation but had surrendered or been captured in recent months. These Acadians, who had once reveled in their freedom to farm the land they had reclaimed from the sea and thrived on what they produced, were now put to work as poorly compensated laborers. With their help, the land would remain fertile and yield bumper crops for years to come, but the Acadians would have to stand by and watch as those who had taken their place reaped the rewards.”

Much of the re-population of Acadie/Nova Scotia also came from other communities driven out of their homes by poverty and/or the British Empire. One brutal population clearance replaced another, Acadians out, dispossessed Scots in, then starving Irish in. Some of the Scottish crofters driven out by the Highland Clearances (1750-1860) arrived in Nova Scotia (as well as parts of Ontario, and the Carolinas). Ireland had long suffered from a combination of colonial neglect and exploitation, prompting emigration especially from the less fertile western regions (including Ennis, which my grandmother and her sister fled from; that's another story to come). Successive periods of famine and recovery led to the direst famine years of the mid-1800s and mass migration, primarily to North America including Nova Scotia.

A history of Irish migration to Canada states that Scots-Irish from the New England colonies and others directly from Ireland were recruited to:

“settle the vacant French farms in Nova Scotia in 1761”, and “Unlike most pioneers, they had no forests to fell, no roads to build, the French habitants having prepared and dyked the rich, red tidelands in the belief the French would be there for a lifetime, and their children and grandchildren after them”.

This re-population effected a transformation of the Acadian landscape. Without concentration into towns or even villages, there had been settlements of family homes scattered along shorelines among the fields generations of each family had reclaimed from the sea, with cleared grazing and wilderness further inland, or smaller Acadian settlements on narrow inlets from which they could fish. Onto that unique rural Acadian landscape a quite different, New England/English landscape of townships was imposed. Rivers had been the main means of transport for Acadians, but the ‘replacement population’ built roads and cleared much wilderness, pushing back the Mi’kmaq and other Amerindien inhabitants.

The newcomers also placed their original home-town names on the landscape, so the rural settlement area of Cobequid became the town of Truro, Chebouctou became Halifax, Pisiguid Windsor, Nepisiquit Bathurst, and Amherst popped up near the ruined Acadian area of Beaubassin, signs of which decayed and disappeared.

Interesting that the Acadians kept the original Mi’kmaq place-names, or francophone versions of them, while British and other later settlers replacing them simply erased the original place-names and substituted nostalgic reminders of their home-towns, Chester, Yarmouth, Falmouth, Liverpool and so on. A long list of original Acadian place-names and the new names replacing them is given in Les Acadiens Des Maritimes, Jean Daigle, Centre d’Etudes Acadiennes, Moncton, 1980, pp. 202-203.

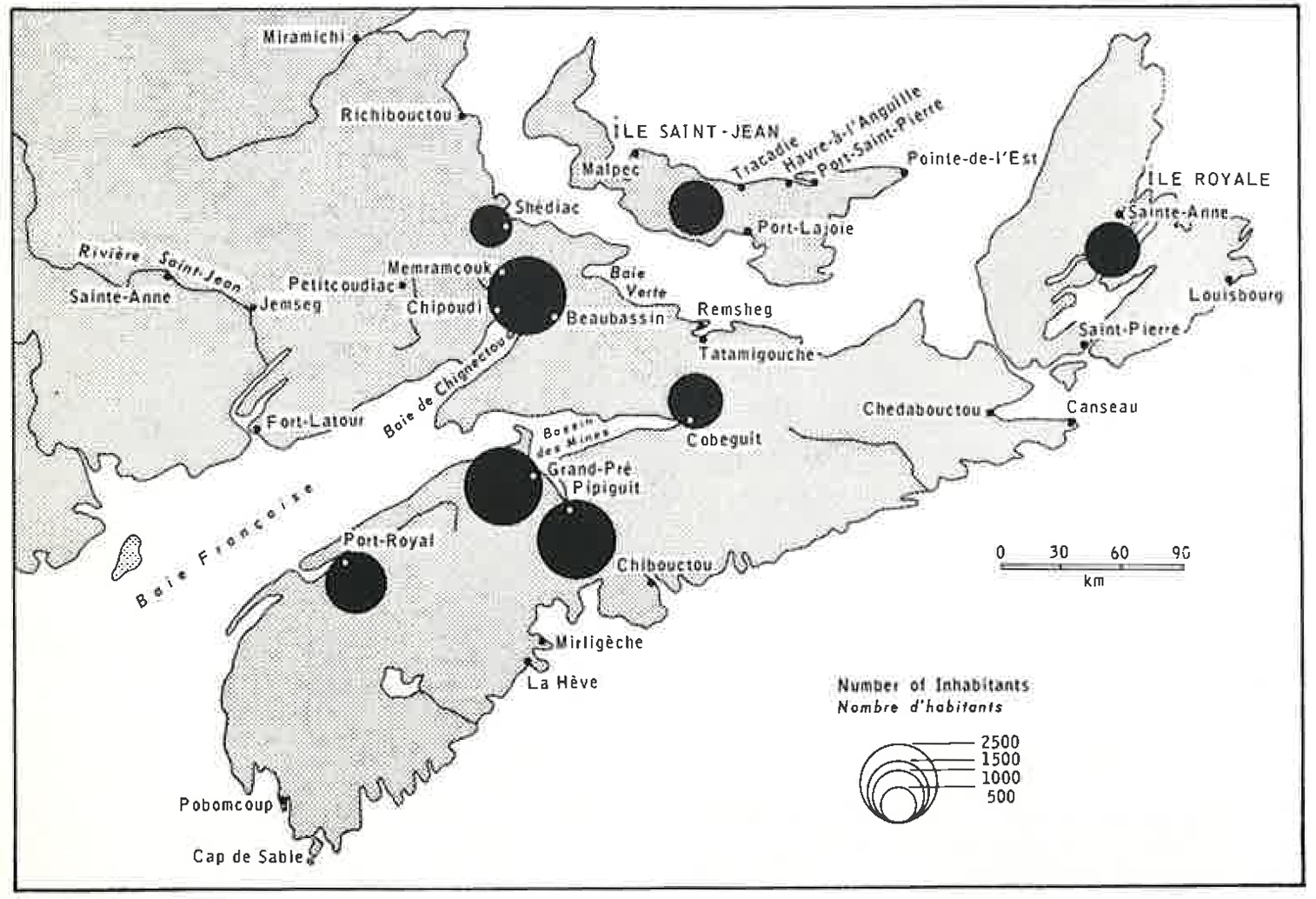

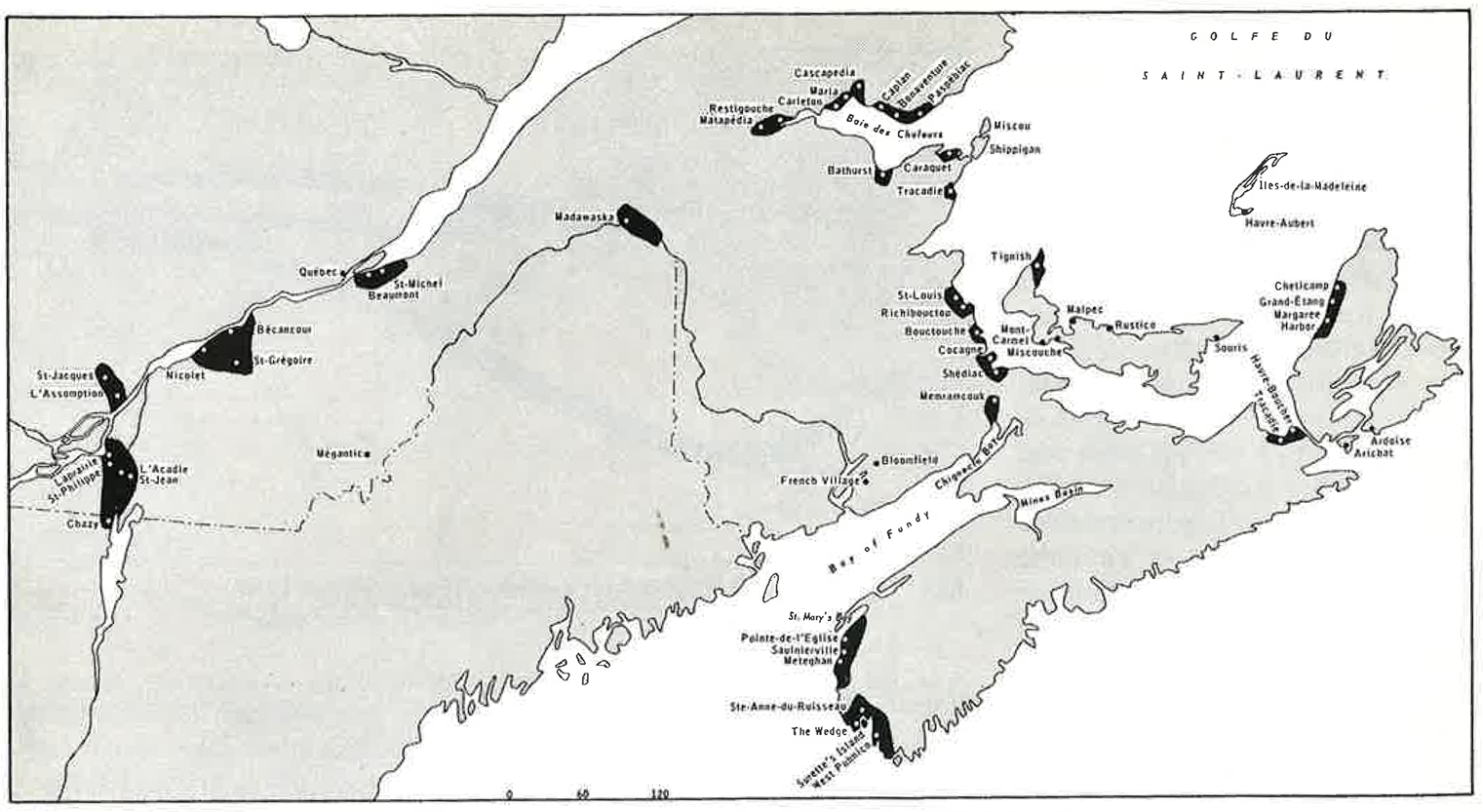

Ponder that for a moment, and the great change in Acadian settlement locations as shown below, and it tells the Acadian story.

Acadian Settlements 1755

Acadian Settlements 1800

So what happened post-1755 was not just removal of the Acadian people, the physical fact of Acadie was erased. And in the process a different ethos or way of life was imposed, tending towards conflict/competition and win/lose, either/or, replacing the original ethos of coexistence, interdependence and mutual benefit. Acadians, who had lived cooperatively with the Mi’kmaq tribes for well over a century, suffered the fate of the many, varied, indigenous peoples of North America: removed, replaced, deracinated. Destroyed, as far as was possible.

While some of the exiled Acadians showed great persistence over many years in reassembling extended families in Louisiana or Québec, many others were determined to return to their homelands; by 1775 1,500 had returned to Acadie/Nova Scotia, by 1800 8,400.

But they led different lives. Acadian returnees took up labouring and menial jobs, “drifting about, searching for a bit of ground to re-root themselves in their native land”. They lived on the margins, with the Mi’kmaq, of their former home. Social hierarchies developed, largely language/heritage-based: English at the top, then English-Loyalist, then Scots (within which were Scotland-based, class-based distinctions), Irish (ditto, but it was the poor Irish who migrated there), and finally Acadian or francophone and Amerindian. That is, those whose heritage went back most generations on those lands were placed at the bottom of the socio-economic pile.

There was a religious dimension to the changes wrought by the expulsion and re-population of Acadie/Nova Scotia/New Brunswick. In Ireland, a British colony, there was a ‘Protestant Ascendancy’ (its members took pride in the name); the famine-ridden poor whose only hope of survival was to migrate were primarily Catholic. Returning Acadians entered into a Nova Scotia which had been made into another Protestant Ascendancy, hostile to Catholic and francophone.

Those Acadians who did make their way back to Nova Scotia were allowed to occupy land in only two of the pre-deportation settlement areas, in Pubnico and on Isle Madame off the coast of Cape Breton. Pubnico, originally Pombomcoup, is on Cape Sable in what became known as Argyle municipality in Yarmouth County on the south-west tip of Nova Scotia (Acadie peninsulaire). Some of the exiled Acadians settling there 1764-84 were from the original families of this area, while others (including a Doucet family) were from distant parts of Acadie. Baie Ste Marie/St Mary’s Bay was one of the new areas where Acadians were allowed to settle post-deportation; the Doucets were among the 12 families settling there, in what had been given the new designation Clare municipality, Digby County. The village of Pointe de l’Eglise/Church Point was founded in 1772 by Francois Doucet and Pierre LeBlanc and their families. Typically, once several families had established in a location, word went out to extended family relatives elsewhere to join them. Pierre Doucet is a case in point. He was five years old in 1755 when the deportation was underway; at 23 while still held in Salem, Massachusetts he married Marie Madeleine LeBlanc and in 1775 after 20 years in exile he, Marie and their children sailed to Clare where his cousin Amable Doucet was already well established.

Other areas of Nova Scotia where returning Acadians were allowed to settle, and are centres of Acadian population today, are Cheticamp (Inverness County, Cape Breton), Pomquet, Tracadie and Havre-Boucher (Antigonish County), Minudie, Nappan and Maccan (Cumberland County), and Chezzetcook (Halifax County). How these ‘new’ Acadian communities fared varied widely according to the locations, land-types and fertility, tenure (tenant, free-holder etc) and neighbours. Many locations where Acadians re-established themselves were far from the most viable. Cheticamp along the Gulf of St Lawrence had been described years earlier as:

“…nothing but rocks covered with firs… some sandy coves into which hardly a boat can enter. This coast is dangerous… Cod is very abundant in this bay, and this attracts vessels there, although they are often lost because of the little shelter it affords.” [tr]

European fishery agents had established themselves on these shores and continued to dominate, keeping Acadian settlers in economic servitude for many years; the hilly terrain and poor soil did not allow much agriculture as an alternative. Displaced Acadians arrived in Cheticamp from many different places and over almost 50 years, far longer than in other locations and surely more because of family connections rather than any natural attractions of the area. One was Marie Doucet, second wife of Pierre Aucoin.

After the Seven Years War ended in Europe in 1763, British militancy in pursuing and persecuting Acadians throughout Acadie/Nova Scotia started to relax. In 1767 the few Acadian settlements along the St John River valley which had escaped British soldiers were authorised to remain. But after the American War of Independence ended in 1783 they suffered another forced dispersal - local British authorities allowed Loyalists from the former British colonies in New England to expropriate Acadian farms and dwellings; the Acadians were told to move and start again on less fertile lands further up the valley, in the Madawaska region (now in Maine/New Brunswick). Some did move there, others fearing yet another dislocation being imposed on them kept moving, into francophone Québec. However, many remained, though not on the sites of their original settlements:

“…perhaps as many as five or six thousand - almost as many as initially expelled - were becoming well rooted in half a dozen scattered nuclei of a new Acadia on the margins of the old, offering quiet evidence that the very attempt to efface such a French presence had insured its survival, through the intensification of regional ethnic identity by so harsh an experience.”

But they were now an isolated (socially as well as geographically) ‘foreign’ minority in their old homeland. Returning Acadians had more lowly, dependent and uncertain status than pre-deportation, depending on the nature of land tenure they obtained and varying local conditions; no longer did they prosper on the rich soils they’d cultivated for generations, and which Lawrence prized. There was sometimes hostility from their new neighbours, the later migrant settlers who’d taken their place in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Captain John MacDonald, surveying one of the new Acadian settlements, Minudie in the newly-named Cumberland area, for the estate-owner in 1795, noted the hostility of nearby British settlers and the meagre habitations of the re-settling Acadians, their one-room houses beside their bigger barns. He reported that the Acadians have:

“customs of their own, of which they are tenacious, some of which are worse and some better than our own”. The neighbouring British “readily see the imperfections on the part of the Acadians… because we are a saucy nation and too ready to despise others - because we happen to be the conquerors… we have destroyed them… While we do not perceive the faults on our own sides… Sure I am that we are not more virtuous or happy than they are and I fear that we have made them worse men and less happy than they have been.”

How much this sentiment was shared in Britain is unclear; there, in a hugely hierarchical and unequal society, with many impoverished and discontented, the fate of the Acadians may well have escaped much notice. But some were revolted by British behaviour in Acadie (as elsewhere). The foremost political commentator of the time, Edmund Burke, observed:

“We did, in my opinion, most inhumanly, and upon pretenses, that, in the eye of an honest man, are not worth a farthing, root out this poor, innocent deserving people, whom our utter inability to govern or to reconcile gave us no sort of right to extirpate.”

Future generations of Acadian returnee families grew up avoiding the attention of authorities and ‘foreign’ neighbours; it is understandable that Acadians managing to get back to Acadie/Nova Scotia were inclined to keep their heads down. But the conditions that returning Acadians found themselves living in were not of their choosing, and as tragic as the forced expulsion itself. Families that had grown up on the low-lying and fertile coastal and riverine lands farmed by previous generations were pushed to the poorest, remotest land (and in some cases pushed off this when they’d made it sustaining over a few years). As Catholics they were denied entry into education or local administration. Without the presence of visiting priests from France and Québec, literacy had already ceased to grow after Acadie/Nova Scotia became formally a British possession in 1713. Denied education and civil engagement post-expulsion, the great majority of Acadian families were illiterate through the coming generations, cementing in place their civic and social as well as physical isolation. Thus the ‘acadian story’ faded from awareness among the new inhabitants of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

“This so-called ‘Grand Dérangement’ served to make the Acadians a factor of no real political importance at all, for a full century. Their land and goods were taken from them and, more important perhaps, their community organisation was shattered. From being an organised and fairly prosperous agricultural society, they were suddenly turned into bands of homeless wanderers scattered in all directions. Privations and hardships cut down their numbers, and poverty and isolation removed their political effectiveness.”

Acadie, meaning lands occupied by Acadians, had changed greatly. That new, reduced Acadia of the 1780s-1880s, in the unwanted corners of their former lands, is memorialised in the Acadian Historical Village at Caraquet in New Brunswick. From its introduction: